- Citadel of Arbil

-

Citadel of Arbil Kurdish: Qelay Hewlêr, Arabic: قلعة أربيل Arbil, Iraq

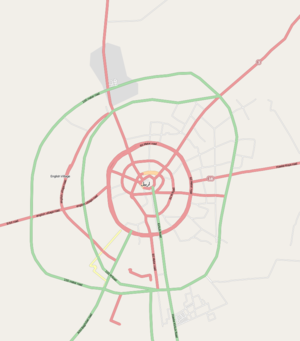

Aerial view of the Citadel of ArbilLocation of the citadel in ArbilCoordinates 36°11′28″N 44°00′32″E / 36.191°N 44.009°ECoordinates: 36°11′28″N 44°00′32″E / 36.191°N 44.009°E Built Unknown Current

conditionPartially ruined Open to

the publicYes Battles/wars Siege by the Mongols (1258) The Citadel of Arbil (Arabic: قلعة أربيل; Kurdish: Qelay Hewlêr) is a tell or occupied mound, and the historical city centre of Arbil in Iraq. It has been claimed that the site is the oldest continuously inhabited town in the world.[1]

The earliest evidence for occupation of the citadel mound dates to the 5th millennium BC, and possibly earlier. It appears for the first time in historical sources during the Ur III period, and gained particular importance during the Neo-Assyrian period. During the Sassanian period and the Abbasid Caliphate, Arbil was an important centre for Christianity. After the Mongols captured the citadel in 1258, the importance of Arbil declined. During the 20th century, the urban structure was significantly modified, as a result of which a number of houses and public buildings were destroyed. In 2007, the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) was established to oversee the restoration of the citadel. In the same year, all inhabitants, except one family, were evicted from the citadel as part of a large restoration project. Since then, archaeological research and restoration works have been carried out at and around the tell by various international teams and in cooperation with local specialists. The government plans to have 50 families live in the citadel once it is renovated.

The buildings on top of the tell stretch over a roughly oval area of 430 by 340 metres (1,410 × 1,120 ft) occupying 102,000 square metres (1,100,000 sq ft). The only religious structure that currently survives is the Mulla Afandi Mosque. The mound rises between 25 and 32 metres (82 and 105 ft) from the surrounding plain. When it was fully occupied, the citadel was divided in three districts or mahallas: from east to west the Serai, the Takya and the Topkhana. The Serai was occupied by notable families; the Takya district was named after the homes of dervishes, which are called takyas; and the Topkhana district housed craftsmen and farmers.

Contents

History

Prehistory

The site of the citadel may have been occupied as early as the Neolithic period, as pottery fragments possibly dating to that period have been found on the slopes of the mound. Clear evidence for occupation comes from the Chalcolithic period, with sherds resembling pottery of the Ubaid and Uruk periods in the Jazira and southeastern Turkey, respectively.[2] Given this evidence for early occupation, the citadel has been called the oldest continuously occupied site in the world.[1][3]

Ur III to the Sassanids

Arbil appears for the first time at the end of the 3rd millennium BC in historical records of the Ur III period as Urbilum. King Shulgi destroyed Urbilum in his 43rd regnal year, and during the reign of his successor Amar-Sin, Urbilum was incorporated into the Ur III state. In the 18th century BC, Arbil appears in a list of cities that were conquered by Shamshi-Adad of Upper Mesopotamia and Dadusha of Eshnunna during their campaign against the land of Qabra. Shamshi-Adad installed garrisons in all the cities of the land of Urbil. During the 2nd millennium BC, Arbil was incorporated into Assyria. Arbil served as a point of departure for military campaigns toward the east.[4][5]

Arbil was an important city during the Neo-Assyrian period. The city took part in the great revolt against Shamshi-Adad V that broke out over the succession of Shalmaneser III. During the Neo-Assyrian period, the name of the city was written as Arbi-Ilu, meaning 'Four Gods'. Arbil was an important religious centre that was compared with cities such as Babylon and Assur. Its goddess Ishtar of Arbil was one of the principal deities of Assyria, often named together with Ishtar of Nineveh. Her sanctuary was repaired by the kings Shalmaneser I, Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. Inscriptions from Assurbanipal record oracular dreams inspired by Ishtar of Arbil. Assurbanipal probably held court in Arbil during part of his reign and received there envoys from Rusa II of Urartu after the defeat of the Elamite ruler Teumman.[4]

After the end of the Assyrian Empire, Arbil was first controlled by the Medes and then incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire before it became part of the empire of Alexander the Great after the Battle of Gaugamela, which was fought near Arbil in 331 BC.[6] The Roman and Parthian Empire fought over control of Arbil, or Arbira as it was known in that period, and the city became an important Christian centre. During the Sassanid period, Arbil was the seat of a governor. In 340 AD, Christians in Arbil were persecuted and in 358, the governor became a martyr when he converted to Christianity.[7] A Nestorian school was founded in Arbil by the School of Nisibis in c. 521.[8] During this period, Arbil was also the site of a Zoroastrian fire temple.[9]

Muslim conquest until the Ottomans

Arbil was conquered by the Muslims in the 7th century. It remained an important Christian centre until the 9th century, when the bishop of Arbil moved his seat to Mosul. From the first half of the 12th century until 1233, Arbil was the seat of the Begteginids, a Turkman dynasty that rose to prominence under the reign of Zengi, the atabeg of Mosul. Muzaffar Din Gökburi, the second dynast of the Begtegenid dynasty and a staunch supporter of Saladin, created a lower town around the city on the citadel mound and founded hospitals and madrasahs. Gökburi died in 1233 without an heir and control of Arbil shifted to the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mustansir after he had besieged the city.[7][10]

When the Mongols invaded the Near East in the 13th century, they attacked Arbil for the first time in 1237. They plundered the lower town but had to retreat for an approaching Caliphal army before they could capture the citadel.[11] After the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols in 1258, they returned to Arbil and were able to capture the citadel after a siege lasting six months.[12] The Mongols appointed a Christian governor to the town and there was an influx of Jacobites, who were allowed to build a church. Persecutions of Christians started however in 1289, leading up to the massacre of all Christians in both the lower town and the citadel town in 1310.[7]

During the Ottoman period, Arbil was part of the province of Baghdad, which was established in 1535. In 1743, the city was held for a short time by the Afsharid ruler Nader Shah after a siege lasting 60 days.[7] An engraving from 1820 shows that at that time both the citadel mound and the plain at its southern foot were occupied.[13] Mohammed Khor, a local Kurdish beg of Rowanduz, controlled Arbil for a short period in 1862. In 1892, the town had approximately 3,200 inhabitants, including a sizeable Jewish minority.[3]

Modern period

During the 20th century, the citadel witnessed significant urban and social changes. A 15-metre (49 ft) high steel water tank was erected on the citadel in 1924, providing the inhabitants with purified water, but also causing water damage to the foundations of the buildings due to increased water seepage. The number of inhabitants gradually declined over the 20th century as the city at the foot of the citadel grew and wealthier inhabitants moved to larger, modern houses with gardens.[13] In 1960, over 60 houses, a mosque and a school were demolished to make way for a straight road connecting the southern gate with the northern gate.[14] Some reconstruction works were carried in 1979 on the citadel's southern gate and the hammam. In 2007, the remaining 840 families were evicted from the citadel as part of a large project to restore and preserve the historic character of the citadel. These families were offered financial compensation. One family was allowed to continue living on the citadel to ensure that there would be no break in the possible 8,000 years of continuous habitation of the site, and the government plans to have 50 families live in the citadel once it is renovated.[15] In 2004, the Kurdish Textile Museum opened its doors in a renovated mansion in the southeast quarter of the citadel.[16]

Architecture and layout

The citadel is situated on a large tell – or settlement mound – of roughly oval shape that is between 25 and 32 metres (82 and 105 ft) high. The area on top of the mound measures 430 by 340 metres (1,410 × 1,120 ft) and is 102,000 square metres (1,100,000 sq ft) large. Natural soil has been found at a depth of 36 metres (118 ft) below the present surface of the mound.[17] The angle of the citadel mound's slopes is c. 45°.[3] Three ramps, located on the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the mound, lead up to gates in the outer ring of houses. The southern gate was the oldest and was rebuilt at least once, in 1860, and demolished in 1960. The current gate house was constructed in 1979. The eastern gate is called the Harem Gate and was used by women. It seems unclear when the northern gate was opened. One source claims that it was opened in 1924,[13] while another observes that there were only two gates in 1944 – the southern and eastern gates.[3]

During the early 20th century, there were three mosques, two schools, two takyas and a hammam on the citadel.[18] The citadel also housed a synagogue until 1957.[17] The only religious structure that currently survives is the Mulla Afandi Mosque, which was rebuilt on the location of an earlier 19th-century mosque.[19] The hammam was built in 1775 by Qassim Agha Abdullah. It went out of service during the 1970s and was renovated in 1979, although many original architectural details were lost.[17][20]

When it was still occupied, the citadel was divided in three districts or mahallas: from east to west the Serai, the Takya and the Topkhana. The Serai was occupied by notable families; the Takya district was named after the homes of dervishes, which are called takyas; and the Topkhana district housed craftsmen and farmers. An inventory made in 1920 shows that at time the citadel was divided in 506 house plots. Since that time, the number of houses and inhabitants has gradually declined. For example, in 1984, 4,466 people lived in 375 houses whereas a 1995 census showed that the citadel had only 1,631 inhabitants living in 247 houses.[18] Until the opening-up of the main north–south thoroughfare, the streets on the citadel mound radiated outward from the southern gate like the branches of a tree. Streets were between 1 and 2.5 metres (3 ft 3 in and 8 ft 2 in) wide and ranged in length from 300 metres (980 ft) for major alleyways to 30–50 metres (98–160 ft) for cul-de-sacs.[21]

The perimeter wall of the citadel is not a continuous fortification wall, but consists of the façades of approximately 100 houses that have been built against each other. Because they have been built on or near the steep slope of the citadel mound, many of these façades were strengthened by buttresses to prevent their collapse or subsidence.[22] There were circa 30 city-palaces; most of them located along the perimeter of the citadel.[23] The oldest surviving house that can be securely dated through an inscription was built in 1893. The oldest houses can be found on the southeastern side of the mound, whereas houses on the northern perimeter date to the 1930s–1940s.[24][25] Before the introduction of modern building techniques, most houses on the citadel were built around a courtyard. A raised arcade overlooking the courtyard, a flat roof and a bent-access entrance to prevent views of the courtyard and the interior of the house were characteristic elements of the houses on the citadel.[23]

Research and restoration

In 2006 and 2007, a team from the University of West Bohemia, together with Salahaddin University in Arbil, carried out an extensive survey and evaluation of the entire citadel. As part of this project, geodetic measurements of the citadel were taken and these were combined with satellite imagery, regular photographic imagery and aerial photographs to create a map and digital 3D model of the citadel mound and the houses on top of it. Geophysical prospection was carried out in some areas of the citadel to detect traces of older architecture buried under the present houses. Archaeological investigations included an archaeological survey on the western slope of the citadel mound, and the excavation of a small test trench in the eastern part of the citadel.[26]

A Neo-Assyrian chamber tomb was found at the foot of the citadel mound during construction activities in 2009. It was subsequently excavated by the local Antiquities Service and archaeologists from the German Archaeological Institute (DAI). The tomb was plundered in antiquity but still contained pottery dating to the 8th and 7th centuries BC.[27] The cooperation between the Antiquities Service and the DAI was continued later that year with a further investigation of the tomb and with a small excavation nearby and geophysical survey of the surrounding area, in which also students from Salahaddin University participated. These investigations revealed the presence of architecture probably dating to the Neo-Assyrian period, as well as more burials belonging to subsequent centuries.[28]

In 2007, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) established the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) to preserve and restore the citadel with the help of UNESCO.[1] Among other things, the HCECR advocates the establishment of a zone extending up to 300–400 metres (980–1,300 ft) from the citadel in which building height should be restricted to approximately 10 metres (33 ft). This would ensure the visual dominance of the citadel over its surroundings.[29] On 8 January 2010, the HCECR and the Iraqi State Board for Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) submitted the Citadel of Erbil to the Iraqi Tentative List of sites that are considered for nomination as World Heritage Site. The submission states that "The Citadel is today one of the most dramatic and visually exciting cultural sites not only in the Middle East but also in the world."[1] Two further agreements between the HCECR and UNESCO were signed in March 2010, and it was disclosed that Arbil Governorate will finance the restoration project with US$13 million.[30] The first restoration works have been carried out in June 2010.[31]

References

- ^ a b c d "Erbil Citadel - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5479/. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 276

- ^ a b Villard 2001

- ^ Eidem 1985, p. 83

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 260

- ^ a b c d Sourdel 2010

- ^ Morony 1984, p. 359

- ^ Morony 1984, p. 132

- ^ Cahen 2010

- ^ Woods 1977, pp. 49–50

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008, p. 261

- ^ a b c "History". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ErbilCitadel/history.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Historical Evolution". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/UrbanContext/HistoricalEvolution.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Qassim Khidhir Hamad. "The pride of erbil needs urgent care". www.niqash.org. http://www.niqash.org/content.php?contentTypeID=74&id=2635&lang=0. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Ivan Watson. "Kurds Displaced in Effort to Preserve Ancient City". www.npr.org. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7133379#7140666. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Nováček et al. 2008, p. 262

- ^ a b "Mahallas". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/Demography/Mahallas.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "The Mosque". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ArchitecturalHeritage/TheMosque.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "The Hammam". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ArchitecturalHeritage/TheHammam.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Alleyways". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/UrbanContext/Alleyways.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Perimeter Wall". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/UrbanContext/PerimeterWall.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Houses". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ArchitecturalHeritage/Houses.php?page=1. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE 01". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/ArchitecturalHeritage/index1.php. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Urban Growth". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/UrbanContext/UrbanGrowth.php?page=1. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Nováček et al. 2008

- ^ Kehrer 2009

- ^ Kehrer 2010

- ^ "The Citadel & The City". www.erbilcitadel.org. http://www.erbilcitadel.org/TheCitadel&TheCity/. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "UNESCO and the Kurdistan Regional Government partner to restore one of the oldest continually-inhabited sites of the World; the Erbil Citadel : UNESCO". www.unesco.org. http://www.unesco.org/en/iraq-office/single-view/news/unesco_and_the_kurdistan_regional_government_partner_to_restore_one_of_the_oldest_continually_inhabi/back/9623/cHash/caad0997a8/. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ McDermid 2010

Sources

- Cahen, Cl. (2010), "Begteginids", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E. et al., Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Eidem, Jesper (1985), "News from the eastern front: the evidence from Tell Shemshāra", Iraq 47: 83–107, ISSN 0021-0889, http://www.jstor.org.proxy.uchicago.edu/stable/4200234

- Kehrer, Nicole (2009), "Deutsche Experten untersuchen assyrische Grabstätte in Arbil" (in German), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, http://www.dainst.org/index.php?id=852800d5bb1f14a199870017f0000011, retrieved 8 July 2010

- Kehrer, Nicole (2010), "Deutsche Archäologen arbeiten wieder im Irak" (in German), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, http://www.dainst.org/index.php?id=ca357fcfc99014b46043001c3253dc21, retrieved 8 July 2010

- McDermid, Charles (29 July 2010), "A Facelift for an Ancient Kurdish Citadel", Time (Time), http://www.time.com/time/travel/article/0,31542,2007282,00.html, retrieved 2 August 2010

- Morony, Michael G. (1984), Iraq after the Muslim conquest, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691053950

- Nováček, Karel; Chabr, Tomáš; Filipský, David; Janiček, Libor; Pavelka, Karel; Šída, Petr; Trefný, Martin; Vařeka, Pavel (2008), "Research of the Arbil Citadel, Iraqi Kurdistan, First Season", Památky Archeologické 99: 259–302, ISSN 0031-0506, http://www.kar.zcu.cz/ovp/data/blob.php?table=internet_list&name=FileName&type=FileType&file=Data&id=IDInternet&idname=200, retrieved 13 July 2010

- Sourdel, D. (2010), "Irbil", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E. et al., Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Villard, Pierre (2001), "Arbèles", in Joannès, Francis (in French), Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Bouquins, Paris: Robert Laffont, pp. 68–69, ISBN 9782221092071

- Woods, John E. (1977), "A note on the Mongol capture of Isfahān", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 36 (1): 49–51, ISSN 0022-2968, http://www.jstor.org.proxy.uchicago.edu/stable/544126?seq=1

External links

- Citadel Documentation Project lfgm.fsv.cvut.cz

- High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization erbilcitadel.org

- Research of the citadel at Arbil, Iraqi Kurdistan kar.zcu.cz

Categories:- Buildings and structures in Arbil

- Archaeological sites in Iraq

- Castles in Iraq

- Cultural Sites on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.