- Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

-

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sz. 106, BB 114 is one of the best-known compositions by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Commissioned by Paul Sacher to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Basel Chamber Orchestra, the score is dated September 7, 1936. The work was premiered in Basel, Switzerland, on January 21, 1937 by the Basel Chamber Orchestra conducted by Sacher, and it was published the same year by Universal Edition.

Contents

Analysis

As its title suggests, the piece is written for string instruments (violins, violas, cellos, double basses, and harp), percussion instruments (xylophone, snare drum, cymbals, tam-tam, bass drum, and timpani) and celesta. The ensemble also includes a piano, which may be classified as either a percussion or string instrument (the celesta player also plays piano during 4-hand passages). Bartók divides the strings into two groups which he directs should be placed antiphonally on opposite sides of the stage, and he makes use of antiphonal effects particularly in the second and fourth movements.

The piece is in four movements, the first and third slow, the second and fourth quick. All movements are written without key signature:

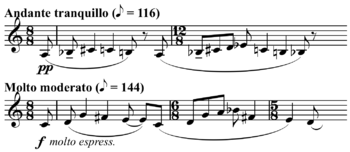

- Andante tranquillo

- Allegro

- Adagio

- Allegro molto

The first movement is a slow fugue. Its time signature changes constantly. It is based around the note A, on which the movement begins and ends. It begins on muted strings, and as more voices enter the texture thickens and the music becomes louder until the climax. Mutes are then removed, and the music becomes gradually quieter over gentle celesta arpeggios. The movement ends with the fugue subject played softly over its inversion. Material from the first movement can be seen as serving as the basis for the later movements, and the fugue subject recurs in different guises at points throughout the piece.

The second movement is quick, with a theme in 2/4 time which is transformed into 3/8 time towards the end. It is marked with loud syncopic piano and percussion accents in a whirling dance, evolving in an extended pizzicato section, with a piano concerto-like conclusion.

The third movement is slow, an example of what is often called Bartók's "Night music", and features timpani glissandi which was an unusual technique at the time of the work's composition, as well as a prominent part for the xylophone. It is also commonly thought that the rhythm of the xylophone solo that opens the third movement is based on the Fibonacci sequence as this "written-out accelerando/ritardando" uses the rhythm 1:2:3:5:8:5:3:2:1.

The last movement, which begins with notes on the timpani and strummed pizzicato chords on the strings, has the character of a lively folk dance.

Place in Bartók's oeuvre

Bartók's next piece was the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, another work which gives a prominent role to percussion and keyboard instruments. Another work which Bartók composed for Sacher was his Divertimento of three years later.

Popular culture

The popularity of the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta is demonstrated by the use of themes from this work in films and popular music. The second movement of this work accompanies "Craig's Dance of Despair and Disillusionment" from the film Being John Malkovich. The Adagio movement was used as the theme music for The Vampira Show (1954–1955), and it was also featured in the Stanley Kubrick film The Shining. It also was the soundtrack for the 1978 Australian film Money Movers. Also the Music is sampled by Anthony "Ant" Davis from the underground hip hop group Atmosphere, from Minneapolis, on the song "Aspiring Sociopath" of their album Lucy Ford. The architect Steven Holl used the overlapping strettos that occur in this piece as a parallel on which the form of the Stretto House (1989) in Dallas, Texas was made.

The novel "City of Night" (1962) by John Rechy makes reference to "Music for Strings Percussion & Celesta" (p. 145, passim), a work which haunts the main character.

Discography

The first recording of the work was by the Los Angeles Chamber Symphony under Harold Byrns,[1] which until 1952 was still being described as the best version.[2]

Other recordings include:

- Ferenc Fricsay and the Symphony orchestra of the RIAS of Berlin (1954)

- Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1958)

- Leopold Stokowski and the Leopold Stokowski Orchestra (1959)

- Antal Doráti and the London Symphony Orchestra

- Yevgeny Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra (1965)

- Pierre Boulez and the BBC Symphony Orchestra (1967)

- Neville Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields (1970)

- Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Mariss Jansons and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra

- Charles Dutoit and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra (1987)

- Iván Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra (1987)

- Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (1997)

References

- ^ "Central Opera Service Bulletin" (PDF). Winter, 1977-78. http://www.cpanda.org/pdfs/csob/2001.pdf. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ^ "Music: New Records, Feb. 18, 1952 :". TIME. 1952-02-18. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,822142,00.html?promoid=googlep. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

External links

- Chapter 7 of Larry Solomon's Symmetry as a Compositional Determinant (an analysis of some formal aspects of the piece)

Categories:- Compositions by Béla Bartók

- 1936 compositions

- Compositions for string orchestra

- Percussion music

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.