- Repetitive strain injury

-

Repetitive Strain Injury Classification and external resources DiseasesDB 11373 eMedicine pmr/97 MeSH D012090 Repetitive strain injury (RSI) (also known as repetitive stress injury, repetitive motion injuries, repetitive motion disorder (RMD), cumulative trauma disorder (CT), occupational overuse syndrome, overuse syndrome, regional musculoskeletal disorder) is an injury of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems that may be caused by repetitive tasks, forceful exertions, vibrations, mechanical compression (pressing against hard surfaces), or sustained or awkward positions.[1] Different sections of this article present contrasting perspectives regarding the causes of RSI.

Types of RSIs that affect computer users may include non-specific arm pain[2] or work related upper limb disorder (WRULD). Conditions such as RSI tend to be associated with both physical and psychosocial stressors.[3]

Contents

Causes

RSI is believed by many to be caused due to lifestyle without ergonomic care[citation needed], E.g. While working in front of computers, driving, traveling etc. Simple reasons like 'Using a blunt knife for everyday chopping of vegetables', may cause RSI.

Other typical habits that some sources believe lead to RSI:[citation needed]

- Reading or doing tasks for extended periods of time while looking down.

- Sleeping on an inadequate bed/mattress or sitting in a bad armchair and/or in an uncomfortable position.

- Carrying heavy items.

- Holding one's phone between neck and shoulder.

- Watching TV in incorrect position e.g. Too much to the left/right.

- Sleeping with head forward, while traveling.

- Prolonged use of the hands, wrists, back, neck, etc.

- sitting in the same position for a long period of time.

Illness

Symptoms

The following complaints are typical in patients who might receive a diagnosis of RSI:[4]

- Short bursts of excruciating pain in the arm, back, shoulders, wrists, hands, or thumbs (typically diffuse – i.e. spread over many areas).

- The pain is worse with activity.

- Weakness, lack of endurance.

In contrast to carpal tunnel syndrome, the symptoms tend to be diffuse and non-anatomical, crossing the distribution of nerves, tendons, etc. They tend not to be characteristic of any discrete pathological conditions.

Frequency

A 2008 study showed that 68% of UK workers suffered from some sort of RSI, with the most common problem areas being the back, shoulders, wrists, and hands.[5]

Physical examination and diagnostic testing

The physical examination discloses only tenderness and diminished performance on effort-based tests such as grip and pinch strength—no other objective abnormalities are present. Diagnostic tests (radiological, electrophysiological, etc.) are normal. In short, RSI is best understood as an apparently healthy arm that hurts. Whether there is currently undetectable damage remains to be established.

Definition

The term "repetitive strain injury" is most commonly used to refer to patients in whom there is no discrete, objective, pathophysiology that corresponds with the pain complaints. It may also be used as an umbrella term incorporating other discrete diagnoses that have (intuitively but often without proof) been associated with activity-related arm pain such as carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, DeQuervain's syndrome, stenosing tenosynovitis/trigger finger/thumb, intersection syndrome, golfer's elbow (medial epicondylosis), tennis elbow (lateral epicondylosis), and focal dystonia.

Finally RSI is also used as an alternative or an umbrella term for other non-specific illnesses or general terms defined in part by unverifiable pathology such as reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (RSDS), Blackberry thumb, disputed thoracic outlet syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, "gamer's thumb" (a slight swelling of the thumb caused by excessive use of a gamepad), "Rubik's wrist" or "cuber's thumb" (tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, or other ailments associated with repetitive use of a Rubik's Cube for speedcubing), "stylus finger" (swelling of the hand caused by repetitive use of mobile devices and mobile device testing.), "raver's wrist", caused by repeated rotation of the hands for many hours (for example while holding glow sticks during a rave).

Although tendinitis and tenosynovitis are discrete pathophysiological processes, one must be careful because they are also terms that doctors often use to refer to non-specific or medically unexplained pain, which they theorize may be caused by the aforementioned processes.

Doctors have also begun making a distinction between tendinitis and tendinosis in RSI injuries. There are significant differences in treatment between the two, for instance in the use of anti-inflammatory medicines, but they often present similar symptoms at first glance and so can easily be confused.

Treatment

On their own, most RSIs will resolve spontaneously provided the area is first given enough rest when the RSI first begins. However, without such care, some RSIs have been known to persist for years, or have needed to be cured with surgery.

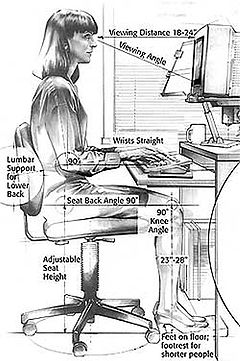

The most often prescribed treatments for repetitive strain injuries are rest, exercise, braces and massage. A variety of medical products also are available to augment these therapies. Since the computer workstation is frequently blamed for RSIs, particularly of the hand and wrist, ergonomic adjustments of the workstation are often recommended.

Ergonomics

Modifications of posture and arm use (ergonomics) are often recommended.[6]

Adaptive software

Main article: List of repetitive strain injury softwareThere are several kinds of software designed to help in repetitive strain injury. Among them, there are speech recognition software, and break timers. Break timers software reminds the user to pause frequently and perform exercises while working behind a computer. There is also automated mouse-clicking software that has been developed, which can automate repetitive tasks in games and applications.

Adaptive hardware

Adaptive technology ranging from special keyboards, mouse replacements to pen tablet interfaces might help improve comfort.

Mouse

Switching to a much more ergonomic mouse, such as a roller mouse, vertical mouse or joystick, or switching from using a mouse to a stylus pen with graphic tablet may provide relief, but in chronic RSI they may result only in moving the problem to another area. Using a graphic tablet for general pointing, clicking, and dragging (i.e. not drawing) may take some time to get used to as well. Switching to a trackpad or pointing stick, which requires no gripping or tensing of the muscles in the arms may help as well. Inertial mice (which do not require a surface to operate) might offer an alternative where the user's arm is in a less stressful thumbs up position rather than rotated to thumb inward when holding a normal mouse. Also, since they do not need a surface to operate ("air mice" function by small, forceless, wrist rotations), the wrist and arm can be supported by the desktop.

Keyboards and keyboard alternatives

Exotic keyboards by manufacturers such as Datahand, OrbiTouch, Maltron and Kinesis are available. Also one can use digital pens to avoid the strain coming from typing itself. Other solutions move the mode of input from one's hands entirely. These include the use of voice recognition software or pedals designed for ergonomics and gaming to supplant normal keyboard input.

Tablet computers

Tablet computers such as the iPad are also valuable to RSI sufferers, since overall strain is much reduced by the keyless nature of the device and the minimal finger movement involved, as well as the much greater variety of body postures while using the device and the replacement of the mouse by a touch screen.[citation needed] Although not a complete solution, it can be a good way to do day-to-day personal computing tasks.

Medical products

A number of medical treatments, including non-narcotic pain medications, braces, and therapy. Although some professionals consider these to be palliative, others consider them to be effective.[7][8]

Pain medications, particularly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are most often used to eliminate pain. The major problem with such drug use with RSIs is that the pain can be masked, and therefore the patient returns to the activities which strained the tissues in the first place before the tissues have had time to heal. So a balance must be struck where pain is reduced, yet not so much that the tissues will be reinjured with continued over-use.

Medical devices are available which help the strained tissues to heal faster. Several types of devices are available, and are classified as either passive or active devices. Passive devices generally immobilize the limb allowing the body to heal itself, while active devices enhance the body's healing capacity[citation needed].

Braces, particularly wrist braces, are by far the most often used products for RSIs[citation needed]. They stabilize the hand and allow healing to occur without further stressing the joint. Braces are available in two basic varieties; soft (i.e., nylon fabric) and hard shell.

Exercise

Exercise decreases the risk of developing RSI.[9]

- Doctors[citation needed] sometimes recommend that RSI sufferers engage in specific strengthening exercises, for example to improve posture.

- In light of the fact that a lifestyle that involves sitting at a computer for extended periods of time increases the probability that an individual will develop excessive kyphosis, theoretically the same exercises that are prescribed for thoracic outlet syndrome or kyphotic postural correction would benefit an RSI sufferer.[10]

- Some sources[who?] recommend motoric exercises and ergo-aerobics to decrease chances of strain injury. Ergo-aerobics target touch typists and people who often use computer keyboard.

Resuming normal activities despite the pain

Psychologists Tobias Lundgren and Joanne Dahl have asserted that, for the most difficult chronic RSI cases, the pain itself becomes less of a problem than the disruption to the patient's life caused by

- avoidance of pain-causing activities

- the amount of time spent on treatment

They claim greater success from teaching patients psychological strategies for accepting the pain as an ongoing fact of life, enabling them to cautiously resume many day-to-day activities and focus on aspects of life other than RSI.[8]

Psychosocial factors

Population studies

Studies have related RSI and other upper extremity complaints with psychological and social factors. A large amount of psychological distress showed doubled risk of the reported pain, while job demands, poor support from colleagues, and work dissatisfaction also showed an increase in pain, even after short term exposure.[11]

For example, the association of Carpal tunnel syndrome with arm use is commonly assumed but not well-established.[12] Typing has long been thought to be the cause of carpal tunnel syndrome,[13] but recent evidence suggests that, if anything, typing may be protective.[14] Another study claimed that the primary risk factors for Carpal tunnel syndrome were "being a woman of menopausal age, obesity or lack of fitness, diabetes or having a family history of diabetes, osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb, smoking, and lifetime alcohol intake."[15]

Psychological exacerbation of symptoms

There are three common mechanisms by which a normally functioning human mind increases pain and pain-related disability.

- Psychological distress (depression and anxiety) make pain seem worse.[16] Chronic pain, regardless of its source, leads to a cycle of increasing depression and reduced physical activity. Reduced physical activity reduces pain in the short term but increases it in the long term.[17]

- Misinterpretation or over-interpretation of pain signals. Psychologists refer to this as pain catastrophizing (the tendency to think the worst when one feels pain),[4] and it is worsened by reliance on patient support groups and internet sites for diagnosis.[18] Gate Control Theory, part of the most accepted medical theory of pain, states that, when we are worried about a particular body part, the brain can actually signal to the spinal cord (via outgoing neurons) that it should be more apt to interpret nerve impulses from that body part as pain and pass them on to the brain.[19] In patients with chronic arm pain, the brain may even learn to automatically trigger pain whenever the limb is moved, as a defense mechanism to prevent further movement[20]

- A sense that something is seriously wrong that does not lessen with normal test results and reassurance from health professionals.[21] Psychologists call this heightened illness concern or health anxiety. (This is commonly seen in psychosomatic illnesses.[22]) The typical RSI patient presents with a strong intuition that their pain indicates existing and ongoing tissue damage.[21] One explanation is that they have a strong "pain alarm"—pain tends to be accepted as a sign of danger and they have difficulty modulating this intuitive uneasiness with pain.[4]

Psychosomatic cases

Some doctors and medical researchers believe that stress is the main cause, rather than a contributing factor, of a large fraction of pain symptoms usually attributed to RSI. The most famous advocate of this point of view, Dr. John E. Sarno, Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine at the New York University Medical School considers that RSI, back pain, and other pain syndromes, although they sometimes have a physical cause, are more often a manifestation of tension myositis syndrome, a psychogenic disorder in which stress causes the autonomic nervous system to reduce blood flow to muscles, causing pain and weakness.[23]

RSI shares many characteristics with known psychosomatic disorders:

- Freud and other psychiatrists believe that diffuse, difficult to describe symptoms likely indicated a psychosomatic root cause for an illness, especially if they moved around the body.[22] (Only some RSI cases fit this description.)

- Psychosomatic illnesses typically display symptoms whose origins are unverifiable but which seem consistent with the time period's understanding of physical (non-psychosomatic) disease processes. When an objective test invented which is able to prove the psychosomatic origins of a specific illness, that illness typically disappears and is replaced by new, undiagnosable sets of symptoms.[22]

- Patients and their advocates usually reject the suggestion that their disease may be non-physical in origin. Doctors frequently avoid giving psychosomatic diagnosis, for fear of angering patients or prompting them to switch doctors.[22] "Psychosomatic" is often misunderstood to mean "faking it" or "imaginary".[22] Other psychosomatic diseases have been known to cause severe pain, paralysis, seizures.[22]

See also

- List of Repetitive Strain Injury software

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.state.nj.us/health/eoh/peoshweb/ctdib.htm

- ^ Teixeira, Tania (2008-12-09). "Technology | The mouse is biting some PC users". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7761262.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ^ Macfarlane, Hunt, Silman. Role of mechanical and psychosocial factors in the onset of forearm pain: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2000

- ^ a b c Ring D, Kadzielski J, Malhotra L, Lee SG, Jupiter JB (February 2005). "Psychological factors associated with idiopathic arm pain". J Bone Joint Surg Am 87 (2): 374–80. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.01907. PMID 15687162. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15687162.

- ^ "Two thirds of office staff suffer from repetitive strain injury | Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. 2008-06-04. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-1024097/Two-thirds-office-staff-suffer-Repetitive-Strain-Injury.html. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ^ Berkeley Lab. Integrated Safety Management: Ergonomics. Website. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Amadio PC (January 2001). "Repetitive stress injury". J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A (1): 136–7; author reply 138–41. PMID 11205849. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11205849.

- ^ a b Living Beyond Your Pain: Using Acceptance & Commitment Therapy to Ease Chronic Pain by Joanne Dahl and Tobias Lundgren

- ^ Ratzlaff, C. R.; J. H. Gillies, M. W. Koehoorn (April 2007). "Work-Related Repetitive Strain Injury and Leisure-Time Physical Activity". Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Care & Research) 57 (3): 495–500. doi:10.1002/art.22610. PMID 17394178.

- ^ Carolyn Kisner & Lyn Allen Colby, Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques, at 473 (5th Ed. 2007).

- ^ Nahit ES, Pritchard CM, Cherry NM, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ (June 2001). "The influence of work related psychosocial factors and psychological distress on regional musculoskeletal pain: a study of newly employed workers". J. Rheumatol. 28 (6): 1378–84. PMID 11409134. http://www.jrheum.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11409134.

- ^ Lozano-Calderón S, Anthony S, Ring D (April 2008). "The quality and strength of evidence for etiology: example of carpal tunnel syndrome". J Hand Surg Am 33 (4): 525–38. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.004. PMID 18406957. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0363-5023(08)00008-7.

- ^ Scangas G, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D (September 2008). "Disparity between popular (Internet) and scientific illness concepts of carpal tunnel syndrome causation". J Hand Surg Am 33 (7): 1076–80. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.03.001. PMID 18762100. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0363-5023(08)00281-5.

- ^ Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Ornstein E, Johnsson R, Ranstam J (November 2007). "Carpal tunnel syndrome and keyboard use at work: a population-based study". Arthritis Rheum. 56 (11): 3620–5. doi:10.1002/art.22956. PMID 17968917. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/116835897/abstract.

- ^ Falkiner S, Myers S (March 2002). "When exactly can carpal tunnel syndrome be considered work-related?". ANZ J Surg 72 (3): 204–9. doi:10.1046/j.1445-2197.2002.02347.x. PMID 12071453. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1445-1433&date=2002&volume=72&issue=3&spage=204.

- ^ Ring D, Kadzielski J, Fabian L, Zurakowski D, Malhotra LR, Jupiter JB (September 2006). "Self-reported upper extremity health status correlates with depression". J Bone Joint Surg Am 88 (9): 1983–8. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00932. PMID 16951115. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16951115.[dead link]

- ^ Turk and Winter. The Pain Survival Guide: How to Reclaim Your Life

- ^ Taylor, Steven J.; Asmundson, Gordon J. G. (2005). It's Not All in Your Head: How Worrying about Your Health Could be Making You Sick—and What You Can Do about It. New York: The Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-993-8.

- ^ Brannon and Feist. Health Psychology: An Introduction to Behavior and Health

- ^ page 193. The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science.

- ^ a b Vranceanu AM, Safren S, Zhao M, Cowan J, Ring D (November 2008). "Disability and psychologic distress in patients with nonspecific and specific arm pain". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466 (11): 2820–6. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0378-1. PMC 2565030. PMID 18636306. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2565030.

- ^ a b c d e f Shorter, Edward (1992). From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. New York: Free Press ; Toronto : Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; New York : Maxwell Macmillan International. ISBN 0-02-928665-4.

- ^ Sarno, John E (2006). The Divided Mind: The Epidemic of Mindbody Disorders. Regan Books. ISBN 978-0060851781.

References

- References that support or promote use of the physical illness concept of RSI

- Repetitive Strain Injury: A Computer User's Guide; Emil Pascarelli and Deborah Quilter (ISBN 0-471-59533-0)

- It's Not Carpal Tunnel Syndrome! RSI Theory and Therapy for Computer Professionals; Suparna Damany, Jack Bellis (ISBN 0-9655109-9-9)

- Conquering Carpal Tunnel Syndrome & Other Repetitive Strain Injuries, A Self-Care Program; Sharon J. Butler (ISBN 1-57224-039-3)

- The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide for Pain Relief, Second Edition; Clair Davies, Amber Davies (ISBN 1-57224-375-9)

- Electromyographic Applications in Pain, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Repetitive Strain Injury Computer User Injury With Biofeedback: Assessment and Training Protocol; Erik Peper, Vietta S Wilson et al. The Biofeedback Foundation of Europe, 1997

- van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (2007). "Repetitive strain injury". Lancet 369 (9575): 1815–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60820-4. PMID 17531890.

- References that are cautious about the use of the physical illness concept of RSI

- Szabo RM, King KJ (September 2000). "Repetitive stress injury: diagnosis or self-fulfilling prophecy?". J Bone Joint Surg Am 82 (9): 1314–22. PMID 11005523. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11005523. Review.

- Ring D, Guss D, Malhotra L, Jupiter JB (July 2004). "Idiopathic arm pain". J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A (7): 1387–91. PMID 15252084. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15252084.

- Quintner JL (July 1995). "The Australian RSI debate: stereotyping and medicine". Disabil Rehabil 17 (5): 256–62. doi:10.3109/09638289509166644. PMID 7626774.

- Hall W, Morrow L (1988). "'Repetition strain injury': an Australian epidemic of upper limb pain". Soc Sci Med 27 (6): 645–9. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90013-5. PMID 3227370.

- Lucire Y. Constructing RSI: Belief and Desire. University of New South Wales Press. 2001

- Brooks P (November 1993). "Repetitive strain injury". BMJ 307 (6915): 1298. doi:10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1298. PMC 1679411. PMID 8257882. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1679411.

External links

- Repetitive Strain Injuries at the Open Directory Project

- Musculoskeletal disorders from the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA)

- Workrave application for prevention of RSI

- Amadio PC (January 2001). "Repetitive stress injury". J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A (1): 136–7; author reply 138–41. PMID 11205849. http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11205849.

- Harvard RSI Action

- Prevention and Management of Repetitive Strain Injury

- My work, my sorrow, a documentary on RSI in France today

Categories:- Disability

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Occupational diseases

- Overuse injuries

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.