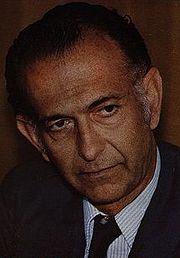

- José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz

-

José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz

Minister of Economy of Argentina In office

March 29, 1976 – March 31, 1981President Jorge Videla Preceded by Joaquín de la Heras Succeeded by Lorenzo Sigaut Minister of Economy of Argentina In office

May 21, 1963 – October 12, 1963President José María Guido Preceded by Eustaquio Méndez Delfino Succeeded by Eugenio Blanco Personal details Born August 13, 1925

SaltaNationality  Argentina

ArgentinaAlma mater University of Cambridge José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz (born August 13, 1925) was an Argentine executive and policy maker. He served as Minister of the Economy under de facto President Jorge Rafael Videla between 1976 and 1981, and shaped economic policy during the self-styled National Reorganization Process military dictatorship.

Contents

Biography

Early career

Martínez de Hoz, the scion of one Argentina's oldest cattle ranching families, was born in Salta, Argentina. Pursuing higher studies at the University of Cambridge, he returned and in 1955, following the coup against the populist Juan Perón, he was appointed his province's Minister of the Economy. Though democracy returned to Argentina three years later, the armed forces continued to exercise vetting power over most policy and in 1963, Martínez de Hoz became one of a series of conservative Argentine Economy Ministers during Jose Maria Guido's brief presidency (an interlude marked by squabbles among the military brass and recession).

Becoming an influential lobbyist for Acindar, one of Argentina's largest steel manufacturers, Martínez de Hoz became its CEO in 1968. Seven years later, after union laborers at Acindar's Villa Constitución plant elected a socialist shop steward, Martínez de Hoz retaliated by using his family's long-standing connections with the armed forces to have them brutally repressed. Supported by Metalworkers Union leader Lorenzo Miguel, security forces abducted the new shop steward, Alberto Piccinini, and about 300 others (most of whom were murdered).[1]

Work as minister of economy

Having become considerably developed, Argentina, by 1975, was nevertheless in the throes of some of the worst instability since 1930. Argentine public opinion turned to the military, who deposed Isabel Perón's weak regime in a March 1976 coup. Inheriting a wave of violence and 700% inflation, the new regime called on Martínez de Hoz, appointing him Minister of the Economy. Anxious to restore business confidence, announced a plan to further open Argentina's markets, believing that the country's national industry was inefficient and uncompetitive internationally. He moved to lessen Argentina's trade barriers quickly, which he believed to be a cause of economic isolation. He enjoyed the personal friendship of David Rockefeller, who facilitated Chase Manhattan and International Monetary Fund loans of nearly US$1 biliion following his appointment.[2]

He decreed a general freeze on wages, and instituted a value-added tax while rescinding the inheritance tax. As a result of the changes instituted by Martínez de Hoz, inflation fell sharply; but, many local retailers and home builders became incapable of coping with the fall in demand and declared bankruptcy.[3]

A year later, the billion-dollar trade deficit had turned around and business investment had soared by about 25%. Real wages, however, had lost nearly 40% of their purchasing power, and while consumer spending remained weak, the shock might have been worse but for hitherto high savings rates. Inflation, in turn, revived, and Martínez de Hoz responded in June, 1977, with deregulation of the financial markets, removing checks on banks and transferring responsibility for any bad loans to the state, which took charge of their debt as needed.[4]

The Central Bank, like many key economic posts in the Martínez de Hoz era, was led by one of a number of Chicago Boys: Adolfo Diz. Diz enacted much of the Economy Minister's financial deregulation policy, while moving to limit domestic credit. He enacted the Monetary Regulation Account Law of 1977, which raised reserve requirements to 45% of deposits, thereby doubling borrowers' interest rates while eliminating yields on demand deposits.[5]

Short-term financial speculation flourished, while chronic tax evasion and budget deficits remained high. Frequent wage freeze decrees continued to depress living standards generally and income inequality increased.[3]

Sweet Money

Again in recession by 1978, the economy continued to be saddled with inflation around 175%. Image-conscious and so, fearful of possible riots, Martínez de Hoz relented and in December, he issued new, more generous wage guidelines. To address his fellow conservatives' fear that this might lead to even higher inflation, he introduced a novel take on the currency crawling peg: fixed, progressively smaller devaluations of the official exchange rate between the Argentine peso and the US dollar set by a monthly timetable, popularly known as the Tablita.

The Tablita invariably set a slower depreciation of the peso value than what local inflation warranted and although inflation did ease somewhat, imported goods and foreign credit soon became much cheaper than those locally available. Imports almost tripled in volume and by 1980, the peso became one of the most overvalued currencies in the world; its high purchasing power abroad soon had many referring to it as plata dulce ("sweet money"). Record numbers of Argentines now vacationed abroad, often stocking up on appliances; between the suddenly negative trade deficit and tourists' foreign spending, however, this chalked up a then-record US$4 billion annual loss for the national balance sheet in both 1980 and 1981.[3]

Having already suffered from weakened demand, many industries (particularly smaller factories) could not compete with the flood of imports and a second wave of industry bankruptcies began. Ostensibly to avoid a sharp rise in unemployment, Martínez de Hoz took an even more controversial step when he decided to begin absorbing private sector debts (mostly those of the well-connected, including US$700 miliion of Acindar's)[6] into the national debt. One of his chief business interests, the insolvent Compañía Italo Argentina de Electricidad, was nationalized at his orders at a reported cost of US$394 million.[2]

The economy was still in relatively high gear and, with rising fiscal revenues, the nation's finances appeared healthy during 1979 and 1980.[3] Secretly, however (as much of this data was censored at time), local speculators were taking advantage of the overvalued peso by taking up over US$30 billion in loans overseas.[7] This money soon found itself in risky gambles at home and abroad and when one bank's Ponzi scheme collapsed in March, 1980, Martínez de Hoz responded to the possible panic by luring investors with one-year treasury bills, paying 60% in US dollars. Facing these pressures, the Argentine peso increasingly became the object of short-selling by insiders, including Martínez de Hoz himself.[1]

Circular 1050 and the shattered Tablita

Martínez de Hoz addresses the nation in a March 12, 1981, farewell address

The end of his tenure soon near and increasingly unpopular, in April 1980, Martínez de Hoz had the Central Bank promulgate new regulations governing adjustable loans. The Central Bank Circular 1050 tied monthly loan interest payments (almost all lending in Argentina is on an adjustable basis) to the value of the US dollar vis-a-vis the peso. Borrowers were confident that the gradual peso devaluations would continue on schedule and new homeowners rushed to secure (or, refinance) mortgages at these favorable terms.[5] Brokerage houses proliferated as put options against the peso increased sharply and in February, 1981, Martínez de Hoz announced the unthinkable: the time had come for a sharp devaluation. The Tablita was shattered and he retired the following month.[3]

What followed was one of the worst financial crises in the history of modern Argentina. Speculators quickly took advantage of the 1977 deregulation to write off their debts, legitimate borrowers (including many large employers) were faced with suddenly unaffordable US dollar payments and homeowners' monthly payments (tied by the Circular 1050 to the value of the Dollar), rose by over tenfold during the next fifteen months.[8]

Legacy

It took defeat during the disastrous Falklands War in June 1982, to usher in more moderate leadership in the junta. That July, the new Central Bank President, Domingo Cavallo, rescinded the hated "1050." Thousands were saved from financial ruin by this change, but the economic damage would remain.

Business confidence was destroyed by the whole calamity and even though Argentina's productive Agricultural sector brought in over US$34 billion in trade surpluses over the next eight years, none of it sufficed to deal with chronic capital flight or the newly monstrous public debt (US$7 billion at the start of the dictatorship, it had grown to US$43 billion by the time of the restoration of democracy in 1983).[3]

Martínez de Hoz was himself indicted in 1988 for his involvement in the human rights abuses at Acindar and spent 77 days in jail. Quickly freed, he finally benefitted from a pardon by President Carlos Menem in 1990. Returning to world of high finance despite a 1992 conviction of operating a brokerage with a revoked licence, Martínez de Hoz became a member of the board of directors of two Arbitrage houses: Rohm Group and the Banco General de Negocios ("General Business Bank").

The General Business Bank, now defunct, later helped clients illegally wire up to US$30 billion out of the country prior to its December, 2001, financial crisis.[9]

In 2006, a judge declared the pardon unconstitutional and revoked the suspension of the judicial process dictated before, thus leaving the way open to investigate Martínez de Hoz's alleged involvement in the kidnapping and extortion of Federico and Miguel Gutheim (a local textile mill owner and his son) in 1976, as well as the murder of Juan Carlos Casariego (one his own assistants at the Economy Ministry).

Martinez de Hoz was arrested on April 5, 2007, following a Supreme Court ruling deeming the 1990 presidential pardons unconstitutional,[10] and was given a preliminary sentence of house arrest (due to his advanced age) on May 4, 2010, pursuant to his indictment in the Gutheim case.[11]

References

- ^ a b Significativa propuesta realizada a Acindar

- ^ a b Buenos Aires Económico: La saga de los Martínez de Hoz (Spanish)

- ^ a b c d e f Lewis, Paul.The Crisis of Argentine Capitalism. University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

- ^ Crawley, Eduardo. Argentina: A House Divided. St. Martin's Press, 1985.

- ^ a b de Pablo, Juan Carlos. Economists and Economic Policy: Argentina since 1958.

- ^ Inversiones millonarias en medio de los cortes de energía (Spanish)

- ^ National Geographic Magazine. Argentina's New Beginning, August 1986.

- ^ Argentina: From Insolvency to Growth. World Bank Press, 1993.

- ^ Atlas Escolar

- ^ Argentina arrests former dictator's top money man (AFP)

- ^ InfoBAE: Martínez de Hoz fue trasladado a su domicilio tras recibir el alta (Spanish)

- La dictadura militar en Argentina on the Ministry of Education website.

- Una pesada herencia, by Ernesto Hadida.

- "La Justicia anuló los indultos a Martínez de Hoz y Harguindeguy" (in Spanish). Clarín. 4 September 2006. http://www.clarin.com/diario/2006/09/04/um/m-01265295.htm.

- "Argentine junta pardons revoked". BBC News. 6 September 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/5314700.stm.

Preceded by

Joaquín De las HerasMinister of Economy

1976–1981Succeeded by

Lorenzo SigautCategories:- 1925 births

- Living people

- People from Salta Province

- Argentine people of Spanish descent

- Argentine Ministers of Finance

- Argentine businesspeople

- Operatives of the Dirty War

- Prisoners and detainees of Argentina

- Recipients of Argentine presidential pardons

- Alumni of the University of Cambridge

- Argentine anti-communists

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.