- Humanitarian intervention

-

Humanitarian intervention "refers to a state using military force against another state when the chief publicly declared aim of that military action is ending human-rights violations being perpetrated by the state against which it is directed."[1]

There is no one standard or legal definition of humanitarian intervention; the field of analysis (such as law, ethics, or politics) often influences the definition that is chosen. Differences in definition include variations in whether humanitarian interventions is limited to instances where there is an absence of consent from the host state; whether humanitarian intervention is limited to punishment actions; and whether humanitarian intervention is limited to cases where there has been explicit UN Security Council authorization for action.[2] There is, however, a general consensus on some of its essential characteristics:[3]

- Humanitarian intervention involves the threat and use of military forces as a central feature

- It is an intervention in the sense that it entails interfering in the internal affairs of a state by sending military forces into the territory or airspace of a sovereign state that has not committed an act of aggression against another state.

- The intervention is in response to situations that do not necessarily pose direct threats to states’ strategic interests, but instead is motivated by humanitarian objectives.

The subject of humanitarian intervention has remained a compelling foreign policy issue, especially since NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999, as it highlights the tension between the principle of state sovereignty – a defining pillar of the UN system and international law – and evolving international norms related to human rights and the use of force.[4] Moreover, it has sparked normative and empirical debates over its legality, the ethics of using military force to respond to human rights violations, when it should occur, who should intervene, and whether it is effective.

To its proponents, it marks imperative action in the face of human rights abuses, over the rights of state sovereignty, while to its detractors it is often viewed as a pretext for military intervention often devoid of legal sanction, selectively deployed and achieving only ambiguous ends. Its frequent use following the end of the Cold War suggested to many that a new norm of military humanitarian intervention was emerging in international politics, although some now argue that the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the US "war on terror" have brought the era of humanitarian intervention to an end.[5]

Contents

History

Intervening in the affairs of another state has been a subject of discussion in public international law for as long as laws of nations were developed. Attitudes have changed considerably since the end of World War II, the Allied discovery of the Holocaust, and the Nuremberg trials. One of the classic statements for intervention in the affairs of another country is found in John Stuart Mill's essay, A Few Words on Non-Intervention (1859)[6]

"There seems to be no little need that the whole doctrine of non-interference with foreign nations should be reconsidered, if it can be said to have as yet been considered as a really moral question at all... To go to war for an idea, if the war is aggressive, not defensive, is as criminal as to go to war for territory or revenue; for it is as little justifiable to force our ideas on other people, as to compel them to submit to our will in any other respect. But there assuredly are cases in which it is allowable to go to war, without having been ourselves attacked, or threatened with attack; and it is very important that nations should make up their minds in time, as to what these cases are... To suppose that the same international customs, and the same rules of international morality, can obtain between one civilized nation and another, and between civilized nations and barbarians, is a grave error..."

According to Mill's opinion (in 1859) barbarous peoples were found in Algeria and India where the French and British armies had been involved. Mill's justification of intervention was overt imperialism. First, he argued that with "barbarians" there is no hope for "reciprocity", an international fundamental. Second, barbarians are apt to benefit from civilized interveners, said Mill, citing Roman conquests of Gaul, Spain, Numidia and Dacia. Barbarians,

"have no rights as a nation, except a right to such treatment as may, at the earliest possible period, fit them for becoming one. The only moral laws for the relation between a civilized and a barbarous government, are the universal rules of morality between man and man."

While seeming wildly out of kilter with modern discourse, a similar approach can be found in theory on intervention in failed states. Of more widespread relevance, Mill discussed the position between "civilized peoples".

"The disputed question is that of interfering in the regulation of another country’s internal concerns; the question whether a nation is justified in taking part, on either side, in the civil wars or party contests of another: and chiefly, whether it may justifiably aid the people of another country in struggling for liberty; or may impose on a country any particular government or institutions, either as being best for the country itself, or as necessary for the security of its neighbours.

Mill brushes over the situation of intervening on the side of governments who are trying to oppress an uprising of their own, saying "government which needs foreign support to enforce obedience from its own citizens, is one which ought not to exist". In the case however of a civil war, where both parties seem at fault, Mill argues that third parties are entitled to demand that the conflicts shall cease. He then moves to the more contentious situation of wars for liberation.

"When the contest is only with native rulers, and with such native strength as those rulers can enlist in their defence, the answer I should give to the question of the legitimacy of intervention is, as a general rule, No. The reason is, that there can seldom be anything approaching to assurance that intervention, even if successful, would be for the good of the people themselves. The only test possessing any real value, of a people’s having become fit for popular institutions, is that they, or a sufficient portion of them to prevail in the contest, are willing to brave labour and danger for their liberation. I know all that may be said, I know it may be urged that the virtues of freemen cannot be learnt in the school of slavery, and that if a people are not fit for freedom, to have any chance of becoming so they must first be free. And this would be conclusive, if the intervention recommended would really give them freedom. But the evil is, that if they have not sufficient love of liberty to be able to wrest it from merely domestic oppressors, the liberty which is bestowed on them by other hands than their own, will have nothing real, nothing permanent. No people ever was and remained free, but because it was determined to be so..."

Current Approaches to Humanitarian Intervention

Although most writers agree that humanitarian interventions should be undertaken multilaterally, ambiguity remains over which particular agents - the UN, regional organizations, or a group of states - should act in response to mass violations of human rights. The choice of actor has implications for overcoming collective action challenges through mobilization of political will and material resources.[7] Questions of effectiveness, conduct and motives of the intervener, extent of internal and external support, and legal authorization have also been raised as possible criteria for evaluating the legitimacy of a potential intervener.[8]

UN Authorized Interventions

Most states clearly would prefer to secure UN authorization before using force for humanitarian purposes,[9] and would probably agree that the UN Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, can authorize military action in response to severe atrocities and other humanitarian emergencies that it concludes constitute a threat to peace and security.[10]

The understanding of what constitutes threats to international peace has been radically broadened since the 1990s to include such issues as mass displacement, and the UN Security Council has authorized use of force in situations that many states would have previously viewed as “internal” conflicts.[11]

Unauthorized Interventions

In several instances states or groups of states have intervened with force, and without advance authorization from the UN Security Council, at least in part in response to alleged extreme violations of basic human rights. Fairly recent examples include the intervention after the Gulf War to protect the Kurds in northern Iraq as well as NATO’s intervention in Kosovo.

Four distinct attitudes or approaches to the legitimacy of humanitarian intervention in the absence of Security Council authorizations can be identified:[12]

- Status quo: Categorically affirms that military intervention in response to atrocities is lawful only if authorized by the UN Security Council or if it qualifies as an exercise in the right of self-defense.[13] Under this view, NATO’s intervention in Kosovo constituted a clear violation of Article 2(4). Defenders of this position include a number of states, most notably Russia and People's Republic of China.[14] Proponents of this approach point to the literal text of the UN Charter, and stress that the high threshold for authorization of the use of force aims to minimize its use, and promote consensus as well as stability by ensuring a basic acceptance of military action by key states. However, Kosovo war has also highlighted the drawbacks of this approach,[15] most notably when effective and consistent humanitarian intervention is made unlikely by the geopolitical realities of relations between the Permanent Five members of the Security Council, leading to the use of the veto and inconsistent action in the face of a humanitarian crises.

- Excusable breach: Humanitarian intervention without a UN mandate is technically illegal under the rules of the UN Charter, but may be morally and politically justified in certain exceptional cases. Benefits of this approach include that it contemplates no new legal rules governing the use of force, but rather opens an “emergency exit” when there is a tension between the rules governing the use of force and the protection of fundamental human rights.[10][16] Intervening states are unlikely to be condemned as law-breakers, although they take a risk of violating rules for a purportedly higher purpose. However, in practice, this could lead to questioning the legitimacy of the legal rules themselves if they are unable to justify actions the majority of the UN Security Council views as morally and politically justified.

- Customary law: This approach involves reviewing the evolution of customary law for a legal justification of non-authorized humanitarian intervention in rare cases. This approach asks whether an emerging norm of customary law can be identified under which humanitarian intervention can be understood not only as ethically and politically justified but also as legal under the normative framework governing the use of force. However, relatively few cases exist to provide justification for the emergence of a norm, and under this approach ambiguities and differences of view about the legality of an intervention may deter states from acting. The potential for an erosion of rules governing the use of force may also be a point of concern.

- Codification: The fourth approach calls for the codification of a clear legal doctrine or “right” of intervention, arguing that such a doctrine could be established through some formal or codified means such as a UN Charter Amendment or UN General Assembly declaration.[17] Although states have been reluctant to advocate this approach, a number of scholars, as well as the Independent International Commission on Kosovo, have made the case for establishing such a right or doctrine with specified criteria to guide assessments of legality.[18][19] A major argument advanced for codifying this right is that it would enhance the legitimacy of international law, and resolve the tension between human rights and sovereignty principles contained in the UN charter. However, the historical record on humanitarian intervention is sufficiently ambiguous that it argues for humility regarding efforts to specify in advance the circumstances in which states can use force, without Security Council authorizations, against other states to protect human rights.[20]

Responsibility to Protect

See: Responsibility to Protect

Although usually considered to be categorically distinct from most definitions of humanitarian intervention,[21] the emergence of a 'Responsibility to protect' (R2P) deserves mention. Responsibility to Protect is the name of a report produced in 2001 by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) which was established by the Canadian government in response to the history of unsatisfactory humanitarian interventions. The report sought to establish a set of clear guidelines for determining when intervention is appropriate, what the appropriate channels for approving an intervention are and how the intervention itself should be carried out.

Responsibility to protect seeks to establish a clearer code of conduct for humanitarian interventions and also advocates a greater reliance on non-military measures. The report also criticises and attempts to change the discourse and terminology surrounding the issue of humanitarian intervention. It argues that the notion of a 'right to intervene' is problematic and should be replaced with the 'responsibility to protect'. Under Responsibility to Protect doctrine, rather than having a right to intervene in the conduct of other states, states are said to have a responsibility to intervene and protect the citizens of another state where that other state has failed in its obligation to protect its own citizens.

This responsibility is said to involve three stages: to prevent, to react and to rebuild. Responsibility to Protect has gained strong support in some circles, such as in Canada, a handful of European and African nations, and among proponents of human security, but has been criticised by others, with some Asian nations being among the chief dissenters.

Humanitarian Intervention in Foreign Policy Doctrines

See:

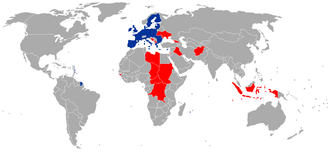

Examples of humanitarian intervention

Examples of past alleged humanitarian interventions include:

- Russian, British and French Anti-Ottoman Intervention in the Greek War of Independence (1824)

- French expedition in Syria (1860-1861)

- Russian Anti-Ottoman Intervention in Bulgaria (1877)

- Spanish–American War (1898)

- United States occupation of Haiti (1915)

- United Nations Operation in the Congo (1964)

- US intervention in Dominican Republic (1965)

- Vietnamese Intervention in Cambodia (1978)

- Uganda-Tanzania War (1979)

- Operation Provide Comfort (Iraq, 1991)[22]

- Unified Task Force (Somalia, 1992)

- Operation Uphold Democracy (Haiti, 1994)

- UNAMIR (Rwanda, 1994)

- UNTAET (East Timor, 1999)

- NATO bombing of Yugoslavia (1999)

- Coalition military intervention in Libya (2011)

The above are only "possible" examples of humanitarian intervention due to the advancement of other reasons of intervention (such as self-defence) as justifications of the use of force. They are, however, academically accepted 'incidences' of humanitarian intervention.[23][24]

Criticism

Many criticisms have been levied against humanitarian intervention.[1] Inter-governmental bodies and commission reports composed by persons associated with governmental and international careers have rarely discussed the distorting selectivity of geopolitics behind humanitarian intervention nor potential hidden motivations of intervening parties. To find less veiled criticism one must usually turn to civil society perspectives, especially those shaped by independent scholars who benefit from academic freedom.[25]

Some argue that humanitarian intervention is a modern manifestation of the Western colonialism of the 19th century. Anne Orford's work is a major contribution along these lines, demonstrating the extent to which the perils of the present for societies experiencing humanitarian catastrophes are directly attributable to the legacy of colonial rule. In the name of reconstruction, a capitalist set of constraints is imposed on a broken society that impairs its right of self-determination and prevents its leadership from adopting an approach to development that benefits the people of the country rather than makes foreign investors happy. The essence of her position is that “legal narratives” justifying humanitarian intervention have had the primary effect of sustaining “an unjust and exploitative status quo”.[26]

Others argue that dominant countries, especially the United States and its coalition partners, are using humanitarian pretexts to pursue otherwise unacceptable geopolitical goals and to evade the non-intervention norm and legal prohibitions on the use of international force. Noam Chomsky and Tariq Ali are at the forefront of this camp, viewing professions of humanitarian motivation with deep skepticism. They argue that the United States has continued to act with its own interests in mind, with the only change being that humanitarianism has become a legitimizing ideology for projection of U.S. hegemony in a post–Cold War world. Ali in particular argue that NATO intervention in Kosovo was conducted largely to boost NATO's credibility.[27][28]

A third type of criticism centers on the event-based and inconsistent nature of most policies on humanitarian intervention. These critics argue that there is a tendency for the concept to be invoked in the heat of action, giving the appearance of propriety for Western television viewers, but that it neglects the conflicts that are forgotten by the media or occur based on chronic distresses rather than sudden crises. Henry Kissinger, for example, finds that Bill Clinton's practice of humanitarian intervention was wildly inconsistent. The US launched two military campaigns against Serbia while ignoring more widespread slaughter in Rwanda, justifying the Russian assault on Chechnya, and welcoming to the United States the second-ranking military official of a widely recognized severe human rights violator - the communist government of North Korea.[29]

Humanitarian intervention has historically consisted of actions directed by Northern states within the internal affairs of Southern states, and has also led to criticism from many non-Western states. The norm of non-intervention and the primacy of sovereign equality are still cherished by the vast majority of states, which see in the new Western dispensation not a growing awareness of human rights, but a regression to the selective adherence to sovereignty of the pre–UN Charter world.[30] During the G-77 summit, which brought together 133 nation-states, the "so-called right of humanitarian intervention" claimed by powerful states was condemned.[31]

See also

- Peacekeeping

- Humanitarian aid

- Nation state

- Responsibility to protect

- Human security

- Imperialism

- Humanitarian bombing

- Mogadishu Line

- Just War Theory

References

- ^ a b Marjanovic, Marko (2011-04-04) Is Humanitarian War the Exception?, Mises Institute

- ^ Jennifer M. Welsh. Humanitarian Intervention and International Relations. Ed. Jennifer M. Welsh. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Alton Frye. 'Humanitarian Intervention: Crafting a Workable Doctrine.' New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2000.

- ^ Shashi Tharoor and Sam Daws. "Humanitarian Intervention: Getting Past the Reefs." World Policy Journal 2001.

- ^ A. Cottey. "Beyond Humanitarian Intervention: The New Politics of Peacekeeping and Intervention." Contemporary Politics 2008: pp. 429-446.

- ^ John Stuart Mill (1859) A Few Words on Non-Intervention at the Online Library of Liberty

- ^ Sumon Dantiki. "Organizing for Peace: Collective Action Problems and Humanitarian Intervention." Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 2005.

- ^ James Pattison. Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect: Who Should Intervene? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- ^ Jason Ladner. Neighbors on Alert: Regional Views on Humanitarian Intervention. Washington DC: The Fund for Peace, 2003.

- ^ a b Danish Institute of International Affairs. Humanitarian Intervention: Legal and Political Aspects. Submitted to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Denmark, December 7, 1999.

- ^ Lori Fisler Dmarosch ed. Enforcing Restraint: Collective Intervention in Internal Conflicts. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1993.

- ^ Jane Stromseth. "Rethinking Humanitarian Intervention: The Case for Incremental Change." Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemnas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Mary Ellen O'Connell. "The UN, NATO, and International Law after Kosovo." Human Rights Quarterly 2000: pgs. 88-89.

- ^ Statements by Russia and China on 24 March 1999, in UN Security Council S/PV.3988.

- ^ Bruno Simma. "NATO, the UN and the Use of Force: Legal Aspects." The European Journal of International Law 1999: pgs. 1-22

- ^ Simon Chesterman. Just War or Just Peace? Humanitarian Intervention and International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ^ Fernando Teson. "The liberal case for humanitarian intervention." Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemnas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Michael Burton. "Legalizing the Sub-Legal: A Proposal for Codifying a Doctrine of Unilateral Humanitarian Intervention." Georgetown Law Journal 1996: pg. 417

- ^ Independent International Commission on Kosovo. Kosovo Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ^ Michael Byers and Simon Chesterman. "Changing the Rules about Rules? Unilateral Humanitarian Intervention and the Future of International Law." Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemnas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Dorota Gierycz. "From Humanitarian Intervention to Responsibility to Protect." Criminal Justice Ethics 2010: pgs.110-128

- ^ The UK based its legal justification for the no-flight restrictions on Iraq on humanitarian intervention. The US based its on UN Security Council Resolution 678.

- ^ Hilpold, Peter, 'Humanitarian Intervention: Is there a Need for a Legal Reappraisal?', European Journal of International Law, 12 (2002), pages 437-467

- ^ Abiew, F. K., The Evolution of the Doctrine and Practice of Humanitarian Intervention, Kluwer Law International (1999)

- ^ Richard Falk. "Humanitarian Intervention: Elite and Critical Perspectives." Global Dialogue 2005

- ^ Anne Orford. Reading Humanitarian Intervention: Human Rights and the Use of Force in International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Noam Chomsky. A New Generation Draws the Line: Kosovo, East Timor, and the Standards of the West. New York: Verso, 2001.

- ^ Tariq Ali. Masters of the Universe? NATO's Balkan Crusade. New York: Verso, 2000.

- ^ Henry Kissinger. Does America Need a New Foreign Policy? New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001.

- ^ Aidin Hehir. "Institutionalizing Impermanence: Kosovo and the Limits of Intervention." Global Dialogue 2005.

- ^ Declaration of the South Summit, 10–14 April 2000

Further reading

- A RIGHT TO INTERFERE. BERNARD KOUCHNER AND THE NEW HUMANITARIANISM by TIM ALLEN and DAVID STYAN

- Nasimi Aghayev, "Humanitäre Intervention und Völkerrecht - Der NATO-Einsatz im Kosovo", Berlin, 2007. ISBN 978-3-89574-622-2

- Lepard, Brian, Rethinking Humanitarian Intervention, Penn State Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02313-9

- Kofi A. Annan, Two Concepts of Sovereignty, Economist, Sep. 18, 1999.

- Josef Bordat, "Globalisation and War. The Historical and Current Controversy on Humanitarian Interventions", in: International Journal of Social Inquiry 2 (2009), 1, 59-72.

- Mark R. Crovelli, "Humanitarian Intervention and the State" http://mises.org/journals/scholar/crovelli2.pdf

- Gareth Evans, Rethinking Collective Action - CASR - edited excerpts - 2004.

- Aidan Hehir, Humanitarian Intervention: An Introduction (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010).

- Gary Klintworth, 'The Right to Intervene in the Domestic Affairs of States', Australian Journal of International Affairs, 46(2) November 1992, pp. 248–266.

- Marjanovic, Marko, Is Humanitarian War the Exception?, Mises Institute (2011)

- Taylor B. Seybolt, "Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Conditions for Success and Failure" (Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Shawcross, W. Deliver Us From Evil: Warlords And Peacekeepers In A World Of Endless Conflict, (Bloomsbury, London, 2000)

- Lyal S. Sunga, ["Is Humanitarian Intervention Legal?" at the e-International Relations website: http://www.e-ir.info/?p=573]

- Lyal S. Sunga, "The Role of Humanitarian Intervention in International Peace and Security: Guarantee or Threat?." The Use of Force in International Relations: Challenges to Collective Security, Int’l Progress Organization & Google Books (2006) 41-79.

- Wheeler, N J, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002)

- Military Intervention on ecological grounds CANINAS, Osvaldo P. Military Intervention on ecological grounds: theoretical construction, legitimacy and repercussions on Brazilian Amazon Forest. Dissertation. MPhil Strategic Studies- Universidade Federal Fluminense. Brazil. 2010. (In Portuguese).

External links

This article relies heavily on the French Wikipedia entry on humanitarian intervention, which was accessed for translation on August 27, 2005.

- Military intervention and the European Union, Chaillot Paper No. 45, March 2001, European Union Institute for Security Studies

- The Ethics of Armed Humanitarian Intervention U.S. Institute of Peace August 2002

- The Argument about Humanitarian Intervention By Michael Walzer

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.