- National Appliance Energy Conservation Act

-

The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act is a 1975 piece of legislation by the United States Congress which regulates energy consumption of specific household appliances in the United States. Though minimum Energy Efficiency Standards were first established by the United States Congress in Part B of Title III of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) (Public Law 94-163).[1] Those standards were then amended by The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1975 (Public Law 100-12), then by The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-357), and later by the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (Public Law 102-486).[1] The latest changes were made by the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-58).[1]

All of these laws and regulations have to do with creating mandatory standards that deal with the energy efficiency of certain household appliances. These standards were put in place to ensure that manufacturers were building products that are at the maximum energy efficiency levels are that are technically feasible and economically justified.[2]

Since these standards have gone into effect they have positively affected both the American economy and the environment. Americans who have purchased these appliances have been saving money on their electricity bills every year. It is estimated that these savings have been greater than $300 billion over time. This money is then reinvested into the economy where is estimated to support over 300,000 American jobs. The majority of American electricity production is from fossil fuels, so by reducing electricity loads less fossil fuels have to be burned. This results in fewer pollutants from being emitted in the process, such as carbon dioxide.[3]

Contents

History

The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1975 (NAECA) was enacted to help create uniform appliance efficiency standards at a time when individual states were creating their own standards.[4] The NAECA established a conservation program for major household appliances, however no real standards came into existence until the 1980s when appliance manufacturers realized it was easier to conform to a uniform federal standard then individual state standards.[4]

The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987

The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987 amended the Energy Policy and Conservation Act and was introduced and supported by democratic Senator Bennett Johnston, Jr. from Louisiana in January 1987.[5] The new amendments to the act established minimum efficiency standards for many household appliances, including[4]:

- Refrigerators

- Refrigerator-Freezers

- Freezers

- Room Air Conditioner

- Fluorescent Lamp Ballasts

- Incandescent Reflector Lamps

- Clothes Dryers

- Clothes Washers

- Dishwashers

- Kitchen Ranges and Ovens

- Pool Heaters

- Television Sets (withdrawn in 1995)

- Water Heaters

Congress set the initial efficiency standards at the start of the act then set a schedule for the United States Department of Energy to review them.[4] The act also put into place laws prohibiting manufacturers from making any representations about the energy efficiency of any product on this list without first being tested by Federal testing procedure, and disclosing the results of such tests.[5] Lastly the new act set new rules for when state regulations will be superseded by federal regulations in regard to testing and labeling requirements, and energy conservation standards.[5]

The Energy Policy Act of 1992

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 took a wider look at energy efficiency and aimed to improve many different areas of energy consumption by creating[6]:

- Building Energy Efficiency Standards

- Equipment Energy Efficiency Standards

- Residential Energy Efficiency Ratings

- Regional Lighting and Building Centers

- Federal Energy Management

- Electric and Gas Utility Regulatory Reform

- Least-Cost Planning for Federal Electric Utilities

- Energy Efficiency R&D

The Bill was original introduced by Democratic Representative Philip Sharp (American politician) of Indiana in February 1991.[7] The particular part of the bill that deals with appliance efficiency is Title I, Subtitle C.[7] It expanded the list of standards previously listed in the NAECA of 1987 to include[4]:

- More types of Fluorescent and Incandescent Reflector Lamps

- Plumbing Products

- Electric Motors

- Commercial Water Heaters

- Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) Systems

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 also provided funding for voluntary consumer information programs for[4]:

- Office Equipment

- Luminaries

- Windows

Th EPAct of 1992 was reviewed in 1997 and it was found that since many of the clauses were written to be voluntary, they were largely ignored.[6] For example, clauses calling for states to voluntarily create laws and regulations in regards to energy efficiency only resulted in a few states actually doing so.[6] It was found during the review that the appliance efficiency clauses (Title I, Subtitle C, mentioned above) was the only part of the Act that had actually been effective in reducing energy consumption.[6]

Energy Policy Act of 2005

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 was introduced by Republican Representative Joe Barton of Texas in April 2005.[8] This Act is the lengthiest one so far listed that has to do with Appliance Energy Conservation. It has within it four major titles[9]:

- Efficiency Title

- Tax Title

- Vehicle Fuel Economy

- Electricity Title

The Efficiency title is of the most concern in amending the NAECA. Firstly, the Act put the United States Department of Energy and the United States Environmental Protection Agency in charge of expanding and monitoring the Energy Star program, and acknowledged the program by listing Energy Star by name in Public Law.[8] The Act also called upon the Federal Trade Commission to reexamine the effectiveness of current EnergyGuide Labeling, and with the assistance of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a new label was developed by 2007.[10] Most importantly, the EPAct of 2005 set new efficiency standards for 16 different products that had not been updated since the last amendments in 1992.[9]

Table of standards for each appliance

Labeling of Appliances

See also: Energy Star Look for this Energystar Logo for more efficient Appliances

Look for this Energystar Logo for more efficient Appliances

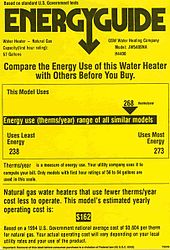

In order for consumers to better understand the different energy efficiencies and cost associated with appliance options, appliances must be labeled to give consumers this information. The appliances the must have this label are Ceiling Fans, Showerheads, Faucets, Water Closets, Urinals, Room Air Conditioners, Water Heaters (all types), Pool Heaters, Furnaces and Boilers, Clothes Washers, Freezers, Refrigerator-Freezers, Refrigerators, Heat Pumps, Central Air Conditioners, Dishwashers, and various types of lamps.[11] The label must show the model number, the size, key features, and display largely a graph showing the annual operating cost in range with similar models, and the estimated yearly energy cost.[12]

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 called for new rules to be made for required and voluntary labeling programs. This spawned the creation of the Energy Guide label and the Energy Star Label?

Using standard test procedures developed by the United States Department of Energy, manufacturers must prove the energy use and efficiency of their product.[13] Test results are printed on a yellow EnergyGuide Label, which manufacturers are required to display on their appliances.[13] The label shows[13]:

- How much energy the appliance uses

- compares the energy use to similar products

- lists approximate annual operating costs

Energy Star is a similar labeling program, but requires more stringent efficiency standards for an appliance to become qualified, and is not a required program, but a voluntary one. Essentially, an Energy Star label shows that the appliance you have chosen uses less energy and will save you more money then it's non-energy star rated competitor

Effects of the National Appliance Energy Act of 1975

Economic Benefit

Appliance energy standards address three market failures that would cause them to be biased toward purchasing more energy intensive appliances. First, low electricity rates cause some consumers to not mind running appliances that are not efficient. Second consumers tend to underestimate the future rate of electricity, thereby underestimating the full lifetime cost of their appliance purchases. Consumers evaluating appliance lifecycle cost tend to use discount rates that are too high which distorts the savings received from using a more efficient appliance. All three of these market failures combine to distort consumers decisions toward purchasing appliances that are less energy efficient than socially desirable.[14] These standards fix these failures by eliminating appliances that are less energy efficient than the standard from the market.

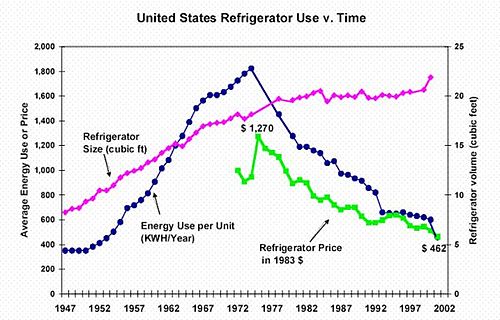

By mandating appliances use electricity more efficiently consumers have gotten better appliances that require less energy to get the same if not more performance. By reducing the electricity required to run appliances consumers have saved tremendous amounts of money since 1975. In many cases the price of these more efficient appliances has not increased compared to previous less efficient models. A great example of this is refrigerators.[15]

The graph above shows refrigerator use in the United States from 1947 until 2002. Before the National Appliance Energy Act of 1975 refrigerators were getting larger in size and using more and more electricity per unit. After 1975 the trend of refrigerator size increasing continued but dramatically after 1975 the electrical use per unit began to decline as a result of the Act. Also importantly after 1975 the price of refrigerators price began to decline. So immediately following this Act consumers in the United States began to get larger refrigerators the use less electricity and cost less per unit. Appliances like refrigerators are essentially always running so these energy improvements since 1975 have saved tremendous amounts of electricity over time.[citation needed] This creates lower utility bills for consumers which allows them to spend their money elsewhere. A refrigerator sold today uses about 70% less electricity as one sold in 1970.[3]

It has been estimated that these standards have saved American taxpayers over $300 Billion in energy savings.[3] Overall these standards have reduced total American energy use by 3.6%, or about 3.6 quadrillion BTU"s every year. Due to the fact that Americans have billions of more dollars every year to reinvest into other sectors of the economy, which they otherwise would not have had without these standards, millions of jobs have been created. It is estimated that these energy savings supported 340,000 American jobs in 2010 [16]. The electricity industry does not support a lot of jobs compared to the amount of revenue it takes in. So, when people reinvest their energy savings into other sectors of the economy that support more jobs per dollar of revenue, jobs are created. These 340,000 jobs created by energy standards represent 0.2% of American jobs a small but beneficial percentage.[3]

Environmental Benefits

The majority of electrical power generation, in the United States, comes from combustion of fossil fuels, which releases carbon dioxide and other pollutants into the atmosphere. 45% of power generation comes from coal, 23% from natural gas, and 1% from petroleum.[17] This totals to about 70% of American electrical consumption being produced from fossil fuels. In the previous section it was discussed that in 2010 3.6 quadrillion BTU's were saved by from the implementation of energy standards. This equates to about 2.52 quadrillion BTU's of energy produced from fossil fuels being abated every year because of these performance standards, or 750,000,000,000 kWh. Production of electricity from coal creates 2.095 pounds of carbon dioxide per kWh, from natural gas 1.321 pounds of carbon dioxide per kWh, and from petroleum 1.969 pounds of carbon dioxide per kWh.[18] This equates to about 500 million tons of carbon dioxide from coal, 160 million tons of carbon dioxide from natural gas, and 10 million tons of carbon dioxide from petroleum. For a total of about 670 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions abated in 2010 alone because of these energy performance standards. Other environmentally degrading emission include sulfur and nitrogen oxides which contribute to acid rain.[19] These emissions are mitigated by energy standards the same way carbon dioxide is as previously shown.

References

- ^ a b c "Laws and Regulations". Appliances & Commercial Equipment Standards. U.S. DOE. http://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/appliance_standards/laws_regs.html. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "About Standards". Appliances & Commercial Equipment Standards. U.S. DOE. http://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/appliance_standards/about_standards.html. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy & Appliance Standards Awareness Project, Appliance and Equipment Efficiency Standards: A Money Maker and Job Creator. January 2011. http://www.aceee.org/research-report/a111

- ^ a b c d e f "History of Federal Appliance Standards". Appliances & Commercial Equipment Standards. U.S. DOE. http://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/appliance_standards/history.html. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "Bill Summary & Status". National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 1987. Library of Congress. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d100:SN00083:@@@L&summ2=m&. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Energy Policy Act of 1992". Energy Efficiency Topics. AEEE. http://www.aceee.org/topics/energy-policy-act-1992. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Bill Summary & Status". Energy Policy Act of 1992. Library of Congress. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d102:HR00776:@@@D&summ2=m&. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Bill Summary & Status". H.R.6. Library of Congress. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d109:HR00006:@@@D&summ2=m&. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Energy Policy Act of 2005". Energy Efficiency. AEEE. http://www.aceee.org/topics/energy-policy-act-2005. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Appliance Labeling". Energy Efficiency. ACEEE. http://www.aceee.org/topics/appliance-labeling. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/edcams/eande/faq.htm#305

- ^ http://www.energystar.gov/ia/business/downloads/FTCs%20Appliance%20Labeling%20Rule.pdf

- ^ a b c "Learn More About EnergyGuide". U.S. EPA, U.S. DOE. http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?c=appliances.pr_energy_guide. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/pss/1802332

- ^ http://www.energetics.com.au/newsroom/media_releases/2007/the_role_of_regulation_in_red)

- ^ Environmental and Energy Study Institute. "Jobs in Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency". http://www.eesi.org/jobs_reee_060111.

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=electricity_in_the_united_states

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/electricity/page/co2_report/co2report.html

- ^ http://environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/acid-rain-overview/

Categories:- 1975 in law

- United States federal energy legislation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.