- n-dimensional sequential move puzzle

-

The Rubik's cube is the original and best known of the three-dimensional sequential move puzzles. There have been many virtual implementations of this puzzle in software. It is a natural extension to create sequential move puzzles in more than three dimensions. Although no such puzzle could ever be physically constructed, the rules of how they operate are quite rigorously defined mathematically and are analogous to the rules found in three-dimensional geometry. Hence, they can be simulated by software. As with the mechanical sequential move puzzles, there are records for solvers, although not yet the same degree of competitive organisation.

Contents

Glossary

- Vertex. A zero-dimensional point at which higher-dimension figures meet.

- Edge. A one-dimensional figure at which higher-dimension figures meet.

- Face. A two-dimensional figure at which (for objects of dimension greater than three) higher-dimension figures meet.

- Cell. A three-dimensional figure at which (for objects of dimension greater than four) higher-dimension figures meet.

- n-Polytope. A n-dimensional figure continuing as above. A specific geometric shape may replace polytope where this is appropriate, such as 4-cube to mean the tesseract.

- n-cell. A higher-dimension figure containing n cells.

- Piece. A single moveable part of the puzzle having the same dimensionality as the whole puzzle.

- Cubie. In the solving community this is the term generally used for a 'piece'.

- Sticker. The coloured labels on the puzzle which identify the state of the puzzle. For instance, the corner cubies of a Rubik cube are a single piece but each has three stickers. The stickers in higher-dimensional puzzles will have a dimensionality greater than two. For instance, in the 4-cube, the stickers are three-dimensional solids.

For comparison purposes, the data relating to the standard 33 Rubik cube is as follows;

Piece count Number of vertices (V) 8 Number of 3-colour pieces 8 Number of edges (E) 12 Number of 2-colour pieces 12 Number of faces (F) 6 Number of 1-colour pieces 6 Number of cells (C) 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1 Number of coloured pieces (P) 26 Number of stickers 54 Number of achievable combinations

There is some debate over whether the face-centre cubies should be counted as separate pieces as they cannot be moved relative to each other. A different number of pieces may be given in different sources. In this article the face-centre cubies are counted as this makes the arithmetical sequences more consistent and they can certainly be rotated, a solution of which requires algorithms. However, the cubie right in the middle is not counted because it has no visible stickers and hence requires no solution. Arithmetically we should have

But P is always one short of this (or the n-dimensional extension of this formula) in the figures given in this article because C (or the corresponding highest-dimension polytope, for higher dimensions) is not being counted.

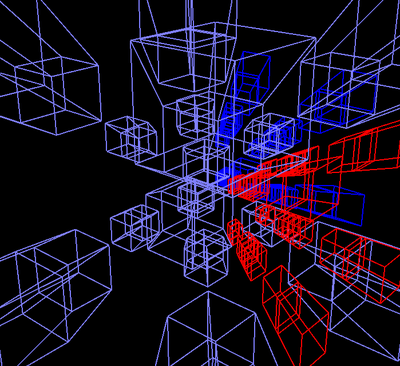

Magic 4D Cube

-

- Geometric shape: tesseract

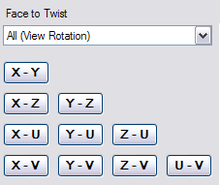

The Superliminal MagicCube4D software is capable of rendering 4-cube puzzles in four sizes, namely 24, the standard 34, 44, and 54. As well as the ability to make moves on the cube there are controls to change the view. These include controls for rotating the whole cube in 3-space and 4-space, 4-D perspective, cubie size and spacing, and sticker size.

Superliminal Software maintains a Hall of Fame for record breaking solvers of this puzzle.

34 4-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 16 Number of 4-colour pieces 16 Number of edges 32 Number of 3-colour pieces 32 Number of faces 24 Number of 2-colour pieces 24 Number of cells 8 Number of 1-colour pieces 8 Number of 4-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1 Number of coloured pieces 80 Number of stickers 216 Achievable combinations:[2]

24 4-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 16 Number of 4-colour pieces 16 Number of edges 32 Number of 3-colour pieces 0 Number of faces 24 Number of 2-colour pieces 0 Number of cells 8 Number of 1-colour pieces 0 Number of 4-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 0 Number of coloured pieces 16 Number of stickers 64 Achievable combinations:[2]

44 4-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 16 Number of 4-colour pieces 16 Number of edges 32 Number of 3-colour pieces 64 Number of faces 24 Number of 2-colour pieces 96 Number of cells 8 Number of 1-colour pieces 64 Number of 4-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 16 Number of coloured pieces 240 Number of stickers 512 Achievable combinations:[2]

54 4-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 16 Number of 4-colour pieces 16 Number of edges 32 Number of 3-colour pieces 96 Number of faces 24 Number of 2-colour pieces 216 Number of cells 8 Number of 1-colour pieces 216 Number of 4-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 81 Number of coloured pieces 544 Number of stickers 1000 Achievable combinations:[2]

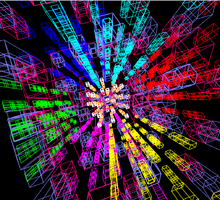

Magic 5D Cube

-

- Geometric shape: penteract

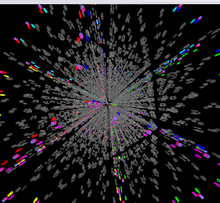

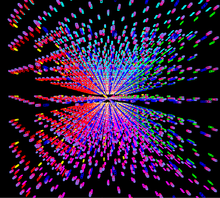

The Gravitation3d Magic 5D Cube software is capable of rendering 5-cube puzzles in six sizes from 25 to 75. As well as the ability to make moves on the cube there are controls to change the view. These include controls for rotating the cube in 3-space, 4-space and 5-space, 4-D and 5-D perspective controls, cubie and sticker spacing and size controls, similar to Subliminal's 4D cube.

However, a 5-D puzzle is much more difficult to comprehend on a 2-D screen than a 4-D puzzle is. An essential feature of the Gravitation3d implementation is the ability to turn off or highlight chosen cubies and stickers. Even so, the complexities of the images produced are still quite severe as can be seen from the screen shots.

Gravitation3d maintains a Hall of Insanity for record breaking solvers of this puzzle. As of 6th, January 2011, there has been two successful solutions for the 75 size of 5-cube.[3]

35 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 80 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 80 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 40 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 10 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1 Number of coloured pieces 242 Number of stickers 810 Achievable combinations:[4]

25 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 0 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 0 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 0 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 0 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 0 Number of coloured pieces 32 Number of stickers 160 Achievable combinations:[4]

45 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 160 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 320 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 320 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 160 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 32 Number of coloured pieces 992 Number of stickers 2,560 55 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 240 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 720 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 1,080 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 810 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 243 Number of coloured pieces 2,882 Number of stickers 6,250 65 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 320 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 1,280 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 2,560 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 2,560 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1,024 Number of coloured pieces 6,752 Number of stickers 12,960 75 5-cube

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 32 Number of 5-colour pieces 32 Number of edges 80 Number of 4-colour pieces 400 Number of faces 80 Number of 3-colour pieces 2,000 Number of cells 40 Number of 2-colour pieces 5,000 Number of 4-cubes 10 Number of 1-colour pieces 6,250 Number of 5-cubes 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 3,125 Number of coloured pieces 13,682 Number of stickers 24,010 Magic 7D Cube

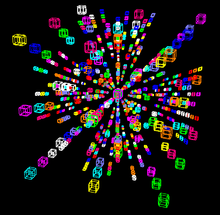

Andrey Astrelin's Magic Cube 7D software is capable of rendering puzzles of up to 7 dimensions in twelve sizes from 34 to 57.

As of May 2011, only 36, 37 and 46 puzzles were solved.[5]

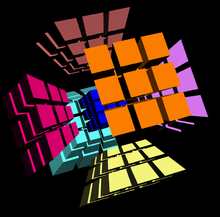

Magic 120-cell

-

- Geometric shape: 120-cell or hecatonicosachoron

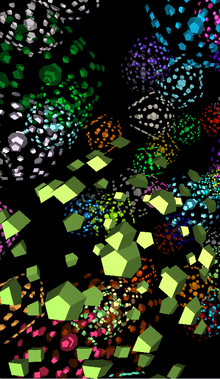

The 120-cell is a 4-D geometric figure (4-polytope) composed of 120 dodecahedrons, which in turn is a 3-D figure composed of 12 pentagons. The 120-cell is the 4-D analogue of the dodecahedron in the same way that the tesseract (4-cube) is the 4-D analogue of the cube. The 4-D 120-cell software sequential move puzzle from Gravitation3d is therefore the 4-D analogue of the Megaminx dodecahedral 3-D puzzle.

The puzzle is rendered in only one size, that is three cubies on a side, but in six colouring schemes of varying difficulty. The full puzzle requires a different colour for each cell, that is 120 colours. This large number of colours adds to the difficulty of the puzzle in that some shades are quite difficult to tell apart. The easiest form is two interlocking tori, each torus forming a ring of cubies in different dimensions. The full list of colouring schemes is as follows;

- 2-colour tori.

- 9-colour 4-cube cells. That is, the same colouring scheme as the 4-cube.

- 9-colour layers.

- 12-colour rings.

- 60-colour antipodal. Each pair of diametrically opposed dodecahedron cells is the same colour.

- 120-colour full puzzle.

The controls are very similar to the 4-D Magic Cube with controls for 4-D perspective, cell size, sticker size and distance and the usual zoom and rotation. Additionally, there is the ability to completely turn off groups of cells based on selection of tori, 4-cube cells, layers or rings.

Gravitation3d has created a "Hall of Fame" for solvers, who must provide a log file for their solution. As of January 2009, Noel Chalmers remains the only person to have solved the puzzle.[6]

Piece count[7] Number of vertices 600 Number of 4-colour pieces 600 Number of edges 1,200 Number of 3-colour pieces 1,200 Number of faces 720 Number of 2-colour pieces 720 Number of cells 120 Number of 1-colour pieces 120 Number of 4-cells 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1 Number of coloured pieces 2,640 Number of stickers 7,560 Achievable combinations:[7]

This calculation of achievable combinations has not been mathematically proven and can only be considered an upper bound. Its derivation assumes the existence of the set of algorithms needed to make all the "minimal change" combinations. There is no reason to suppose that these algorithms will not be found since puzzle solvers have succeeded in finding them on all similar puzzles that have so far been solved.

3x3 2D square

-

- Geometric shape: square

Interestingly, a 2-D Rubik type puzzle can no more be physically constructed than a 4-D one can.[8] A 3-D puzzle could be constructed with no stickers on the third dimension which would then behave as a 2-D puzzle but the true implementation of the puzzle remains in the virtual world. The implementation shown here is from Superliminal who quite perversely call it the 2D Magic Cube.

The puzzle is not of any great interest to solvers as its solution is quite trivial. In large part this is because it is not possible to put a piece in position with a twist. Some of the most difficult algorithms on the standard Rubik's cube are to deal with such twists where a piece is in its correct position but not in the correct orientation. With higher-dimension puzzles this twisting can take on the rather disconcerting form of a piece being apparently inside out. One has only to compare the difficulty of the 2×2×2 puzzle with the 3×3 (which has the same number of pieces) to see that this ability to cause twists in higher dimensions has much to do with difficulty, and hence satisfaction with solving, the ever popular Rubik's cube.

Piece count[1] Number of vertices 4 Number of 2-colour pieces 4 Number of edges 4 Number of 1-colour pieces 4 Number of faces 1 Number of 0-colour pieces 1 Number of coloured pieces 8 Number of stickers 12 Achievable combinations:

The centre pieces are in a fixed orientation relative to each other (in exactly the same way as the centre pieces on the standard 3×3×3 cube) and hence do not figure in the calculation of combinations.

This puzzle is not really a true 2-dimensional analogue of the Rubik's cube. If the group of operations on a single polytope of an n-dimensional puzzle is defined as any rotation of an (n – 1)-dimensional polytope in (n – 1)-dimensional space then the size of the group,

- for the 5-cube is rotations of a 4-polytope in 4-space = 8×6×4 = 192,

- for the 4-cube is rotations of a 3-polytope (cube) in 3-space = 6×4 = 24,

- for the 3-cube is rotations of a 2-polytope (square) in 2-space = 4

- for the 2-cube is rotations of a 1-polytope in 1-space = 1

In other words, the 2D puzzle cannot be scrambled at all if the same restrictions are placed on the moves as for the real 3D puzzle. The moves actually given to the 2D Magic Cube are the operations of reflection. This reflection operation can be extended to higher-dimension puzzles. For the 3D cube the analogous operation would be removing a face and replacing it with the stickers facing into the cube. For the 4-cube, the analogous operation is removing a cube and replacing it inside-out.

1D projection

Another alternate-dimension puzzle is a view achievable in David Vanderschel's 3D Magic Cube. A 4-cube projected on to a 2D computer screen is an example of a general type of an n-dimensional puzzle projected on to a (n – 2)-dimensional space. The 3D analogue of this is to project the cube on to a 1-dimensional representation, which is what Vanderschel's programme is capable of doing.

Vanderschel bewails that nobody has claimed to have solved the 1D projection of this puzzle.[9] However, since records are not being kept for this puzzle it might not actually be the case that it is unsolved.

See also

- Megaminx

- Rubik's cube group

- Tesseract

- 120-cell

- List of Rubik's cube software

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Roice Nelson,Anatomy of a d-dimensional Rubik's Cube, available online here and archived 25th Dec 2008.

- ^ a b c d Eric Balandraud, Calculating the Permutations of 4D Magic Cubes, available online here and archived 25th Dec 2008.

- ^ Roice Nelson, MagicCube5D unsolved puzzles listed online here and archived 25th Dec 2008.

- ^ a b MC5D Permutation Counts

- ^ Magic Cube 7D archived 15th May 2011

- ^ Roice Nelson, Magic120Cell, Roice states that Noel Chalmers is the only person to solve the puzzle on the Gravitation3d website here

- ^ a b David Smith, An Upper Bound for the Number of Different Positions of the Fully-Colored Magic120-Cell, available online here and archived 25th Dec 2008.

- ^ David Vanderschel, "Lower-dimensional cubes", 4D Cubing Forum, 21st Aug 2006. "MC2D's (reflecting) moves would require a 3rd dimension to implement them physically". Retrieved 4th April 2009.

- ^ Vanderschel posting on the 4D Cubing group at Yahoo retrieved and archived 25th Dec 2008.

Further reading

- H. J. Kamack and T. R. Keane, The Rubik Tesseract, available online here and archived 25th Dec 2008.

- Velleman, D, "Rubik's Tesseract", Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Feb., 1992), pp. 27–36, Mathematical Association of America.

- Pickover, C, Surfing Through Hyperspace, pp120–122, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Pickover, C, Alien IQ Test, Chapter 24, Dover Publications, 2001.

- Pickover, C, The Zen of Magic Squares, Circles, and Stars, pp130–133, Princeton University Press, 2001.

- David Singmaster, Computer Cubists, June 2001. A list maintained by Singmaster, including 4D references. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

External links

Categories:- Rubik's Cube

- Combination puzzles

- Puzzles

- Multi-dimensional geometry

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.