- Modoc people

-

For other uses, see Modoc.

Modoc Total population 800 (2000) Regions with significant populations United States –

Languages English, formerly Modoc

Related ethnic groups Klamath, Yahooskin

The Modoc are a Native American people who originally lived in the area which is now northeastern California and central Southern Oregon. They are currently divided between Oregon and Oklahoma. The latter are a federally recognized tribe, the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma. The Oregon Modoc are enrolled in the federally recognized Klamath Tribes.[1]

Modoc Plateau, Modoc National Forest, Modoc County, California; Modoc, Indiana; and numerous other places are named after this group of people.

Contents

History

Pre-contact

Prior to the 19th century, when European explorers first encountered the Modoc, like all Plateau Indians, they caught salmon during salmon runs[citation needed] and migrated seasonally to hunt and gather other food. Their housing included portable tents used in summer, located near reliable sources of edible roots and hunting. In winter, they built earthen dug-out lodges shaped like beehives, covered with sticks and plastered with mud, located near lake shores with reliable sources of seeds from aquatic woka plants and fishing.[2]

Neighboring groups

In addition to the Klamath, with whom they shared a language and the Modoc Plateau, the groups neighboring the Modoc home were the following:

- Shasta on the Klamath River;

- Rogue River Athabaskans and Takelma west over the Cascade Mountains;

- Northern Paiute east in the desert;

- Karuk and Yurok further down the Klamath River; and

- Achomawi or Pit River to the south, in the meadows of the Pit River drainages.

The Modoc, Northern Paiute, and Achomawi shared Goose Lake Valley.[2]

Settlements

The known Modoc village sites are Agawesh where Willow Creek enters Lower Klamath Lake, Kumbat and Pashha on the shores of Tule Lake, and Wachamshwash and Nushalt-Hagak-ni on the Lost River.[3]

First contact

In the 1820s, Peter Skene Ogden, an explorer for the Hudson's Bay Company, established trade with the Klamath people to the north of the Modoc.

South Emigrant Trail established

Lindsay Applegate, accompanied by fourteen other settlers in the Willamette and Rogue valleys in western Oregon, established the South Emigrant Trail in 1846. It connected a point on the Oregon Trail near Fort Hall, Idaho and the Willamette Valley. The new route was created to encourage European-American settlers to western Oregon, to eliminate the hazards encountered on the Columbia Route, to provide an alternate route in the event of trouble with the United Kingdom (the British Hudson's Bay Company controlled the Columbia Route), and to provide a route which would be open for most of the year, except for a short winter season.

Applegate and his party were the first known white men to enter what is now the Lava Beds National Monument. On their exploring trip eastward, they attempted to pass around the south end of Tule Lake, but the rough lava along the shore forced them to seek a route around the north end of the lake.

The opening of the South Emigrant Trail allegedly brought the first regular contact between the Modoc and the European-American settlers, who had largely ignored their territory before. Many of the events of the Modoc War took place along the South Emigrant Trail.

Emigrant invasion

Beginning in 1847, the Modoc raided the invading emigrants on the South Emigrant Trail. The Modoc, numbering about 600 warriors under the leadership of Old Chief Schonchin, inhabited the region around Lower Klamath Lake, Tule Lake, and the Lost River in northern California and southern Oregon.

In September 1852, the Modoc destroyed an emigrant train at Bloody Point on the east shore of Tule Lake. Only three of the 65 persons in the train escaped immediate death. The Modoc took two young girls as captives. They were reportedly killed several years later by jealous Modoc women. The only man to survive the attack made his way to Yreka, California. After hearing his news, Yreka settlers organized a militia under the leadership of Sheriff Charles McDermit, Jim Crosby and Ben Wright. They went to the scene of the massacre to bury the dead and avenge their death. Crosby's party had one skirmish with a band of Modoc and returned to Yreka.

Ben Wright and a small group stayed on to avenge the deaths. He was a notorious Indian hater.[citation needed] Accounts differ as to what took place when Wright's party met the Modoc on Lost River, but most agree that Wright planned to ambush them, which he did in November, 1852. Wright and his forces attacked, killing approximately 40 Modoc, in what came to be known as the "Ben Wright Massacre."

Historians have estimated that at least 300 emigrants and settlers were killed by the Modoc during the years 1846 to 1873.[citation needed] Perhaps as many Modoc were killed by settlers and slave traders.

Treaty with the United States

L to R, standing: US Indian agent, Winema (Tobey) Riddle, a Modoc; and her husband Frank Riddle, with four Modoc women in front. Photographed by Eadweard Muybridge, 1873.[citation needed]

L to R, standing: US Indian agent, Winema (Tobey) Riddle, a Modoc; and her husband Frank Riddle, with four Modoc women in front. Photographed by Eadweard Muybridge, 1873.[citation needed]

The United States, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin band of Snake tribes signed a treaty in 1864, establishing the Klamath Reservation. The treaty required the tribes to cede the land bounded on the north by the 44th parallel, on the west and south by the ridges of the Cascade Mountains, and on the east by lines touching Goose Lake and Henley Lake back up to the 44th parallel. In return, the United States was to make a lump sum payment of $35,000, and annual payments totaling $80,000 over 15 years, as well as providing infrastructure and staff for a reservation. The treaty provided that if the Indians drank or stored intoxicating liquor on the reservation, the payments could be withheld and that the United States could locate additional tribes on the reservation in the future. The tribes requested Lindsay Applegate as the US Indian agent.[citation needed]

The terms of the 1864 treaty demanded that the Modoc surrender their lands in near Lost River, Tule Lake, and Lower Klamath Lake in exchange for lands in the Upper Klamath Valley. They did so, under the leadership of Chief Schonchin. The Indian agent estimated the total population of the three tribes at about 2,000 when the treaty was signed.[citation needed]

The land of the reservation did not provide enough food for both the Klamath and the Modoc peoples. Illness and tension between the tribes increased. The Modoc requested a separate reservation closer to their ancestral home, but neither the federal nor the California government would approve it.[citation needed]

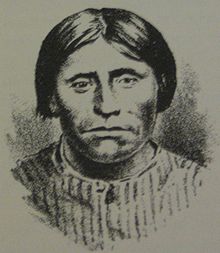

[[Kintpuash (also called Captain Jack) led a band of Modoc in 1870 to leave reservation and return to their traditional homelands. They built a village near the Lost River. These Modoc had not been adequately represented in the treaty negotiations and wished to end the harassment by the Klamath on the reservation.[citation needed]

Modoc War

Main article: Modoc WarIn November 1872, the U.S. Army was sent to Lost River to attempt to force the Keintpuash's band back to the reservation. A battle broke out, and the Modoc escaped to what is called Captain Jack's Stronghold in what is now Lava Beds National Monument, California. The band of less than 53 warriors was able to hold off the 3,000 troops of the U.S. Army for several months, defeating them in combat several times. In April 1873, the Modoc left the Stronghold and began to splinter. Keintpuash and his group were the last to be captured on June 4, 1873, when they voluntarily gave themselves up. The U.S. government personnel had assured them that their people would be treated fairly and that the warriors would be allowed to live on their own land.

The US Army tried, convicted and executed Keintpuash and three of his warriors in October 1873 for the murder of Major General Edward Canby earlier that year at a parley. The general had violated agreements made with the Modoc. The Army sent the rest of the band to Oklahoma as prisoners of war with Scarfaced Charley as their chief. The tribe's spiritual leader, Curley Headed Doctor, also made the removal to Indian Territory.[4]

In the 1870s, Peter Cooper brought Indians to speak to Indian rights groups in eastern cities. One of the delegations was from the Modoc and Klamath tribes. In 1907, the group in Oklahoma was given permission, if they wished, to return to Oregon. Several people did, but most stayed at their new home.

Population

Further information: Population of Native CaliforniaEstimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. James Mooney put the aboriginal population of the Modoc at 400.[5] Alfred L. Kroeber estimated the 1770 Modoc population within California as 500.[6] University of Oregon anthropologist Theodore Stern suggested that there had been a total of about 500 Modoc.[7]

Geography

About 600 members of the tribe currently live in Klamath County, Oregon, in and around their ancestral homelands. This group included the Modocs who stayed on the reservation during the Modoc War, as well as the descendants of those who chose to return to Oregon from Oklahoma in 1909. Since that time, many of them have followed the path of the Klamath. The shared tribal government of the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin in Oregon is known as the Klamath Tribes.

200 Modocs live in Oklahoma on the Quapaw Indian Reservation at the far northeast corner of Oklahoma. They are descendants of the band led by Captain Jack (Keintpuash) during the Modoc War. The Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma was officially recognized by the United States government in 1978, and their constitution was approved in 1991.

Culture

The original language of the Modoc and that of the Klamath, their neighbors to the north, were branches of the family of Plateau Penutian languages. The Klamath and Modoc languages together are sometimes referred to as Lutuamian languages. Both peoples called themselves maklaks, meaning "people". To distinguish between the tribes, the Modoc called themselves Moatokni maklaks, from muat meaning "South". The Achomawi, a band of the Pit River tribe, called them Lutuami, meaning "Lake Dwellers".[2]

The religion of the Modoc is not known in detail. The number 5 figured heavily in ritual, as in the Shuyuhalsh, a five-night dance rite of passage for adolescent girls. A sweat lodge was used for purification and mourning ceremonies.

Further reading

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Mooney, James. 1928. The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections No. 80(7). Washington, D.C.

- Stern, Theodore. 1998. "Klamath and Modoc". In Plateau, edited by Deward E. Walker, Jr. Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant, general editor, vol. 12. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

See also

- Modoc traditional narratives

- Native American history of California

References

- ^ "Appendix O Federally Recognized Indian Tribes with Interest in the Planning Area" (PDF), Western Oregon Plan Revision Final Environmental Impact Statement For the Revision of the Resource Management Plans of the Western Oregon Bureau of Land Management Districts, Oregon State Office, Bureau of Land Management, Portland, Oregon: US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, 2001-02-01, pp. 516–517, http://www.blm.gov/or/plans/wopr/final_eis/files/Volume_4/Volume_IV_App_O.pdf, retrieved 2010-04-06

- ^ a b c Pease, Robert W. (1965). Modoc County; University of California Publications in Geography, Volume 17. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 46–48.

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1925, 1976). Handbook of the Indians of California. 78. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology. pp. 305–335. http://books.google.com/books?id=YDdn0WNMQMYC&dq=%22Handbook+of+the+Indians+of+California%22&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Thrapp, Dan L. (1991-08). "Captain Jack". Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography. 1: A-F. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ Mooney, James (1928). The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico. 80. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. p. 18.

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1925, 1976). Handbook of the Indians of California. 78. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology. p. 883. http://books.google.com/books?id=YDdn0WNMQMYC&dq=%22Handbook+of+the+Indians+of+California%22&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1998-06). "Klamath and Modoc". In Deward E. Walker, William C. Sturtevant, Gen. Edit.. Handbook of North American Indians. 12, Plateau. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 446–456. ISBN 0-16-049514-8.

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1865. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1865: Reports of Agents in Oregon U.S. Office of Indian Affairs, Washington, D.C.

- Waldman, Carl. 1999. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark, New York. ISBN 0-8160-3964-X

External links

- Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

- Klamath Tribes: Klamath, Modoc, Yahooskin, official website

- Southern Oregon Digital Archives

- Modoc, Four Directions Institute

Categories:- Modoc tribe

- Native American tribes in California

- Native American tribes in Oregon

- Native American tribes in Oklahoma

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.