- Máté Csák

-

The native form of this personal name is Csák Máté. This article uses the Western name order.

Máté Csák

Born 1260-65 Died 18. March 1321 Nationality Hungarian Máté (III) Csák (between 1260-65 – 18 March 1321)[1] (Hungarian: Csák (III) Máté, Slovak: Matúš Čák III), also Máté Csák of Trencsén[1] (Hungarian: trencséni Csák (III) Máté, Slovak: Matúš Čák III Trenčiansky) was a Hungarian[2] oligarch in the Kingdom of Hungary who ruled de facto independently the north-western counties of the kingdom (today roughly the western half of present-day Slovakia and parts of Northern Hungary).[3] He held the offices of Marshal (főlovászmester) (1293-1296), Palatine (nádor) (1296-1297, 1301-1310) and Master of the Treasury (tárnokmester) (1310).[4] He could maintain his rule over his territories even after his defeat at the Battle of Rozgony against King Charles I of Hungary. In the 19th century, he was often described as a symbol of the struggle for independence in both the Hungarian and Slovak literatures.[3]

Contents

Early years

He was a son of the Palatine Peter Csák, a member of the Hungarian[2] genus ("clan") Csák.[4] Around 1283, Máté and his brother, Csák inherited their father's possessions, Komárom (Slovak: Komárno) and Szenic (Slovak: Senica).[3] At about that time, they also inherited their uncles' possessions around Nagytapolcsány (Slovak: Veľké Topoľčany, now Topoľčany), Hrussó (Slovak: Hrušovo) and Tata.[3] Their father had started to expand his influence over the territories that surrounded his possessions, but following his death, the members of the rival Kőszegi family strengthened in Pozsony and Sopron counties.[3]

King Andrew's partisan

In 1291, Máté took part in the campaign of King Andrew III of Hungary against Austria.[4] In the next year, when Nicholas Kőszegi rebelled against King Andrew III and occupied Pressburg (Slovak: Prešporok, today Bratislava) and Detrekő (Slovak Plaveč), Máté managed to reoccupy the castles on behalf of the king.[4] Henceforward, the Danube became the border between the developing domains of the Kőszegi and Csák families.[3] King Andrew appointed him to Marshal and he also became the head of Pressburg county.[1] On 28 October 1293, Máté issued a charter and promised that he would respect the liberties of the burghers of the city of Pressburg that King Andrew had confirmed before.[3]

During this period, Máté started to augment his possessions not only by the king's donations, but also by using force.[3] In 1296, he bought Vöröskő (Slovak: Červený Kameň) from its former holders for money; however, contemporary documents prove that he enforced several neighboring landowners to transfer their possessions either to him or his partisans.[3] He even was ready to occupy territories; e.g., around 1296, he took possession of the lands of the Archabbot of Pannonhalma north of the Danube and he also trespassed the possessions of the Collegiate Chapter of Pressburg.[3]

Around the end of 1296, Máté acquired Trencsén (Slovak: Trenčín) and afterwards, he was named after the castle.[3] In 1296 King Andrew appointed him Palatine,[4] but shortly afterwards the king absolved one of Máté's opponents, Andrew of Gimes of all responsibility for the damage he had caused to Máté.[3] The document proves that the relationship of the king and Máté worsened and the king deprived him of his office of Palatine in 1297.[3] At the same time, the king granted Pozsony county to his queen.[3]

The kings' rival

Battle of Rozgony,1312 Chronicon Pictum from 1360

Battle of Rozgony,1312 Chronicon Pictum from 1360

Máté continued to style himself Palatine even after 1297.[1] He managed to overcome Andrew of Gimes and his family and thus expanded his influence along the Zsitva River (Žitava River).[3]

In 1298, King Andrew III allied himself with King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia; the alliance was probably directed against Máté whose possessions lay between the two monarchs' territories [3] In the next year, King Andrew sent his troops against Máté, but he could resist the attack;[1] only Pressburg county was reoccupied by the king's partisans.[3]

Before 1300, Máté entered into negotiations with the representatives of King Charles II of Naples and reassured him that he would assist the claim of his grandson, Charles for the throne against King Andrew III.[3] However, in the summer of 1300, Máté visited King Andrew's court, but the king died on 14 January 1301, and following his death a struggle commenced among the several claimants for the throne. [3] At that time, Máté's brother, Csák died childless and therefore Máté inherited his possessions.[3]

Following the death of King Andrew III, Máté became the Neapolitan prince's follower, but shortly afterwards, he joined the party that offered the crown to Wenceslaus, the son of King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia.[3] He was present at the coronation of the young Czech prince (27 August 1301) who granted him Trencsén and Nyitra counties;[4] therefore he became the lawful holder of all the royal castles and possessions in the two counties.[3] In the following years, Máté Csák occupied the possessions of the Balassa family in the two counties and he also took several castles in Nógrád and Hont counties.[3]

King Wenceslaus could not strengthen his rule against his opponent and he had to leave the kingdom (August 1304).[3] By that time Máté Csák had already left King Wenceslaus' party,[4] and shortly afterwards he made an alliance with Duke Rudolph III of Austria against the king of Bohemia.[3] Although he did not join to King Charles' partisans, but his troops took part in the campaign King Charles and Duke Rudolph lead against the Kingdom of Bohemia (September-October 1304).[3] The internal struggles, however, did not end, because on 6 December 1305 a new claimant, Otto III, Duke of Bavaria was crowned King of Hungary.[3] Máté Csák did not accept King Otto's rule, and his troops struggled together with King Charles' armies who occupied some castles on the northern part of the kingdom.[3]

On 10 October 1307, an assembly confirmed King Charles' rule, but Máté Csák and some other oligarchs (Ladislaus Kán, Ivan and Henry Kőszegi) absented themselves from the assembly.[3] In 1308, Pope Clement V sent a legate to the kingdom in order to strengthen King Charles' position.[3] The legate, Cardinal Gentilis de Montefiori managed to persuade Máté Csák to accept King Charles' rule at their meeting in the Pauline Monastery of Kékes (10 November 1307).[3] Although Máté Csák himself was not present at the following assembly (27 November) in Pest where King Charles' reign was again confirmed, he sent his envoy to attend at the meeting.[3] Shortly afterwards, King Charles appointed Máté Palatine of the kingdom.[4] However, at the new coronation of King Charles (15 June 1309), he was only represented by one of his followers.[3] In the next year, King Charles appointed him to the office of Master of the Treasury.[1]

Máté Csák did not want to accept the king's rule; therefore, he did not attend King Charles' third coronation, when he was crowned with the Holy Crown of Hungary (27 August).[3] Moreover, Máté Csák still continued to expand the borders of his domains and occupied several castles in the northern part of the kingdom.[3] On 25 June 1311, he led his troops towards Buda and pillaged the surrounding territories and on this account the Cardinal Gentilis excommunicated him[1] (6 July 1311. [3] However, he did not accept the punishment and persuaded some priests to continue their services on his territories.[3]

The indignant oligarch pillaged the possessions of the Archdiocese of Esztergom.[3] When the citizens of Kassa (Slovak: Košice) killed Amade Aba, the powerful oligarch of the north-eastern parts of the kingdom (5 September 1311) Máté made an alliance with his sons against the king who sided with Kassa.[3] Máté's troops liberated Sáros Castle (Slovak: Šarišský hrad), besieged by the king, and then marched against Kassa.[3] At the Battle of Rozgony, the king's armies defeated Máté's and his allies' troops (15 June 1312).[1] Following the battle, the king occupied the territories of Amade Aba's sons.[3] Although Máté's domain stayed undisturbed, the occupation of the neighboring territories by the king hindered his expansion.[3]

His last years

In 1314, the king's armies invaded Máté Csák's domain, but they could not occupy it.[3] In the meantime, Máté occupied some fortresses in the March of Moravia and therefore King John of Bohemia also invaded his territories (May 1315).[3] The Czech armies defeated his troops (whom he encouraged in Hungarian language) at Holics but they could not occupy the fortress.[3] King Charles also invaded Máté's domain and occupied Visegrád.[3]

In 1316, some of his former followers rebelled against him, and although he occupied their castle Jókő, but some of them left his domain.[3] In 1317, he invaded the possessions of the Diocese of Nyitra, and his troops occupied and pillaged its see.[3] As a consequence, the Bishop of Nitra excommunicated him and his followers again.[3]

The king's armies continued to invade his territories and occupied Sirok and Fülek (Fiľakovo), but Máté could maintain his rule over his territories until his death.[3]

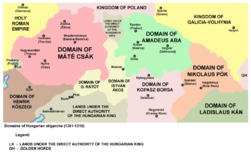

His domain

Máté Csák's domain had been developing gradually before the Battle of Rozgony, and it reached its greatest territorial extent around 1311.[3] By that time, 14 counties of the kingdom, and about 50 castles were under his and his followers' rule.[1]

Around 1297, he organized his own court, similar to the king's court and he usurped royal prerogatives on his domains, similarly to other oligarchs (e.g., Amade Aba, Nicholas Kőszegi) of the beginning of the 14th century.[3] Thus he became the de facto ruler of his domain and he made alliances independently of the king.[3] He refused to accept appeals against his decisions to the king and he denied to put claimants in possession of lands the king had granted them on his territories.[3] Although some of the local landowners did not want to accept Máté's supremacy, but sooner or later, they had to leave their possessions.[3]

Following his death, his cousin Stephen Sternberg became the head of his domain,[1] because his son had died and his grandsons were still minors at the time of his death.[3] However, Stephen Sternberg could not resist the king's invasion and Máté Csák's former domain was occupied by the king's armies in some months.[3]

Afterlife

During the period of Slovak national revival in the 18th and 19th centuries, Máté Csák and his "realm" became the symbols of Slovak independence with the purpose to expropriate his historical heritage for the expectant national state of Slovakia.[citation needed] According to Slovak historian Peter Macho, the national myth that a separate and independent Slovak state existed within Hungary during the 13th century[when?] is very impressive.[5] It was Alexander Boleslav Vrchovský[who?] who first[when?] proposed that Máté Csák was a "Slovak King".[6] Later numerous Slovak poets and writers claimed the Hungarian oligarch for the Slovak national history.[6] Ľudovít Štúr, the most prominent personality in the period of the Slovak national revival presented Máté Csák in his poem Matus z Trencina ("Máté of Trencsén") as champion of Slovak interests, predicting that the Slovak nation "will be free one day".[7] Ján Nepomuk Bobula[who?][when?] described Máté Csák as an invincible patriot who fought for the Slovak nation's freedom until he had been betrayed by which his fate was sealed.[5] In 1881 Czech archeologist Josef Ladislav Píč identified the magnate's Upper Hungarian "realm" as "the first Slovakia independent of the Hungarian King".[6] Slovak historian and linguist Jozef Škultéty[when?] elevated Máté Csák into the Slovak national pantheon in 1938 with his work titled Matúš Čák Trenčiansky a jeho vláda na Slovensku ("Máté Csák of Trencsén and His Rule in Slovakia").[6] The view of the older Slovak histography is that under the decades of Máté Csák's rule "Slovakia was an independent country" but after being defeated "Slovakia became part of Hungary again".[8] According to a new generation of Slovak scholars:[9]

Máté Csák was hardly a Slovak patriot as some 19th century historians have claimed. He pursued the ordinary goals of a Hungarian magnate and never did establish a sufficiently well-defined territory or political organization to support any Slovak claims to a heritage.—Anton Špiesz, Dušan Čaplovič, Ladislaus J. Bolchazy; Illustrated Slovak history: a struggle for sovereignty in Central Europe (2006); p.51See also

- Beckov Castle - owned and fortified by Máté Csák

- Amade Aba - oligarch who ruled de facto independently the northern and north-eastern counties of the Kingdom of Hungary[1]

- Ladislaus Kán - oligarch who governed de facto independently the Transylvanian parts of the Kingdom of Hungary[1]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kristó, Pál; Makk, Ferenc. Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9-14. század).

- ^ a b Peter A. Toma; Dušan Kováč (2001). Slovakia: from Samo to Dzurinda. Hoover Institution Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780817999513. "...The greatest magnates were Matus Cak (Matthew Cak) of Trencin and the Amadeis of the Aba...The Caks, of Magyar origin, had begun their rise during the rules of Stephen V and Ladislas IV..."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be Kristó, Gyula. Csák Máté.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Markó, László. A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig.

- ^ a b Macho, Peter; KREKOVIČ, E. – MANNOVÁ, E. – KREKOVIČOVÁ, E. (2005). "Matúš Čák Trenčiansky - slovenský kráľ?". Mýty naše slovenské. Bratislava: Academic Electronic Press. pp. 104–110. ISBN 80-88880-61-0.

- ^ a b c d Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Basingstoke, UK (Foreword by Professor Peter Burke): Palgrave Macmillan. p. 815. ISBN 13: 978–0–230–55070.

- ^ Stanislav J. Kirschbaum (16 September 1996). A history of Slovakia: the struggle for survival. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 102. ISBN 9780312161255.

- ^ Joseph M. Kirschbaum (1960). Slovakia: nation at the crossroads of central Europe. R. Speller. p. 185. "Matus Cak succeeded in upholding his rule in Slovakia until 1321, but was defeated, and Slovakia became a part of old Hungary"

- ^ Anton Špiesz; Duśan Čaplovič; Ladislaus J. Bolchazy (30 July 2006). Illustrated Slovak history: a struggle for sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 51. ISBN 9780865164260.

Sources

- Engel, Pál: Magyarország világi archontológiája (1301-1457) (The Temporal Archontology of Hungary (1301-1457)); História - MTA Történettudományi Intézete, 1996, Budapest; ISBN 963 8312 43 2.

- Kristó, Gyula: Csák Máté (Máté Csák); Gondolat, 1986, Budapest; ISBN 963 281 736 2.

- Kristó, Gyula (General Editor) - Engel, Pál (Editor) - Makk, Ferenc (Editor): Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9-14. század) (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History /9th-14th centuries/); Akadémiai Kiadó, 1994, Budapest; ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Markó, László: A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig - Életrajzi Lexikon (The High Officers of the Hungarian State from Saint Stephen to the Present Days - A Biographical Encyclopedia); Magyar Könyvklub, 2000, Budapest; ISBN 963 547 085 1.

External links

Categories:- 1260s births

- 1321 deaths

- History of Hungary

- History of Slovakia

- Hungarian nobility

- People excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church

- Palatines of the Kingdom of Hungary

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.