- Commonplace book

-

This article is about the commonplace book. For the music album, see commonplace (album).

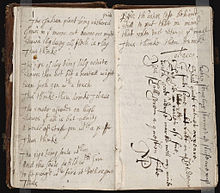

Commonplace books (or commonplaces) were a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They became significant in Early Modern Europe.

"Commonplace" is a translation of the Latin term locus communis (from Greek tópos koinós, see literary topos) which means "a theme or argument of general application", such as a statement of proverbial wisdom. In this original sense, commonplace books were collections of such sayings, such as John Milton's commonplace book. Scholars have expanded this usage to include any manuscript that collects material along a common theme by an individual.

Such books were essentially scrapbooks filled with items of every kind: medical recipes, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, proverbs, prayers, legal formulas. Commonplaces were used by readers, writers, students, and humanists as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts they had learned. Each commonplace book was unique to its creator's particular interests.

Contents

History

Zibaldone

The Italian peninsula, during the course of the 14th-century, was the site of a development of two new forms of book production: the deluxe registry book and the zibaldone (or hodgepodge book). What differentiated these two forms was their language of composition: a vernacular.[1]Giovanni Rucellai, the compiler of one of the most sophisticated examples of the genre, defined it as a "salad of many herbs."[2]

Zibaldone were always paper codices of small or medium format – never the large desk copies of registry books or other display texts. They also lacked the lining and extensive ornamentation of other deluxe copies. Rather than miniatures, zibaldone often incorporate the author's sketches. Zibaldone were in cursive scripts (first chancery minuscule and later mercantile minuscule) and contained what Armando Petrucci, the renowned palaeographer, describes as "an astonishing variety of poetic and prose texts."[3] Devotional, technical, documentary and literary texts appear side-by-side in no discernible order. The juxtaposition of gabelle taxes paid, currency exchange rates, medicinal remedies, recipes and favourite quotations from Augustine and Virgil portrays a developing secular, literate culture.[4] By far the most popular of literary selections were the works of Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio: the "Three Crowns" of the Florentine vernacular traditions.[5]These collections have been used by modern scholars as a source for interpreting how merchants and artisans interacted with the literature and visual arts of the Florentine Renaissance.

English

By the 17th century, commonplacing had become a recognized practice that was formally taught to college students in such institutions as Oxford[citation needed]. John Locke appended his indexing scheme for commonplace books to a printing of his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.[6] The commonplace tradition in which Francis Bacon and John Milton were educated had its roots in the pedagogy of classical rhetoric, and “commonplacing” persisted as a popular study technique until the early 20th century. Both Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were taught to keep commonplace books at Harvard University (their commonplace books survive in published form). Commonplacing was particularly attractive to authors. Some, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Mark Twain, kept messy reading notes that were intermixed with other quite various material; others, such as Thomas Hardy, followed a more formal reading-notes method that mirrored the original Renaissance practice more closely. The older, "clearinghouse" function of the commonplace book, to condense and centralize useful and even "model" ideas and expressions, became less popular over time.

Contemporary evaluations

Critically, many of these works are not seen to have literary value to modern editors. However, the value of such collections is the insights they offer into the tastes, interests, personalities and concerns of their individual compilers.

From the standpoint of the psychology of authorship, it is noteworthy that keeping notebooks is in itself a kind of tradition among litterateurs. A commonplace book of literary memoranda may serve as a symbol to the keeper, therefore, of the person's literary identity (or something psychologically not far-removed), quite apart from its obvious value as a written record. That commonplace books (and other personal note-books) can enjoy this special status is supported by the fact that authors frequently treat their notebooks as quasi-works, giving them elaborate titles, compiling them neatly from rough notes, recompiling still neater revisions of them later, and preserving them with a special devotion and care that seems out of proportion to their apparent function as working materials.

Producing a commonplace is known as commonplacing.

Some modern writers see blogs as an analogy to commonplace books.[7]

Examples in manuscript

- Zibladone da Canal merchant's commonplace book (New Haven, CT, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, MS 327)

- Robert Reynes of Acle, Norfolk (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Tanner 407)].

- Richard Hill, a London grocer (Oxford, Balliol College, MS 354).

- Glastonbury Miscellany. (Trinity College, Cambridge, MS 0.9.38). Originally designed as an account book.

- Jean Miélot, 15th century Burgundian translator and author. His book is in the BnF, and the main sources for his verses, many written for court occasions.

Published examples

- Francis Bacon, "The Promus of Formularies and Elegancies", Longman, Greens and Company, London, 1883. The Promus was a rough list of elegant and useful phrases gleaned from reading and conversation that Bacon used as a source book in writing and probably also as a promptbook for oral practice in public speaking.

- John Milton, “Milton’s Commonplace Book,” in John Milton: Complete Prose Works, gen. ed. Don M. Wolfe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953). Milton kept scholarly notes from his reading, complete with page citations to use in writing his tracts and poems.

- E.M. Forster, "Commonplace Book," ed. Philip Gardner (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985).

- W.H. Auden, "A Certain World," (New York: The Viking Press, 1970).

- Lovecraft, H.P.. "Commonplace Book". H.P. Lovecraft's Commonplace Book. Wired. http://www.wired.com/beyond_the_beyond/2011/07/h-p-lovecrafts-commonplace-book/. Retrieved 5 July 2011. Transcribed by Bruce Sterling.

Literary references to commonplacing

- Bronson Alcott, 1877: “The habit of journalizing becomes a life-long lesson in the art of composition, an informal schooling for authorship. And were the process of preparing their works for publication faithfully detailed by distinguished writers, it would appear how large were their indebtedness to their diary and commonplaces. How carefully should we peruse Shakespeare’s notes used in compiling his plays—what was his, what another’s—showing how these were fashioned into the shapely whole we read, how Milton composed, Montaigne, Goethe: by what happy strokes of thought, flashes of wit, apt figures, fit quotations snatched from vast fields of learning, their rich pages were wrought forth! This were to give the keys of great authorship!” Amos Bronson Alcott, Table-Talk of A. Bronson Alcott (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1877), p. 12.

- Virginia Woolf, mid-20th century: "[L]et us take down one of those old notebooks which we have all, at one time or another, had a passion for beginning. Most of the pages are blank, it is true; but at the beginning we shall find a certain number very beautifully covered with a strikingly legible hand-writing. Here we have written down the names of great writers in their order of merit; here we have copied out fine passages from the classics; here are lists of books to be read; and here, most interesting of all, lists of books that have actually been read, as the reader testifies with some youthful vanity by a dash of red ink." Virginia Woolf, “Hours in a Library,” Granite and Rainbow: Essays by Virginia Woolf (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1958), p. 25.

- In Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events a number of characters including Klaus Baudelaire and the Quagmire triplets keep commonplace books.

- In Michael Ondaatje's The English Patient, Count Almásy uses his copy of Herodotus's Histories as a commonplace book.

See also

Notes

- ^ Armando Petrucci, Writers and Readers in Medieval Italy, trans. Charles M. Radding (New Haven: Yale UP: 1995), 185.

- ^ Dale V. Kent, Cosimo de' Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron's Oeuvre (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2000), p. 69

- ^ Petrucci, 187.

- ^ An example is the Zibaldone da Canal merchant's manual held at the Beinecke Library, which dates from 1312 and contains hand-drawn diagrams of Venetian ships and descriptions of Venice's merchant culture.

- ^ Kent, pg. 81.

- ^ "The Glass Box And The Commonplace Book"

- ^ Blogs as modern day commonplaces:

- "Blogs, Definitions and Commonplace Books"

- "Historical roots of blogging"

- McDaniel, W. Caleb. "The Roots of Blogging." Chronicle of Higher Education. 51.47 (2005): B2.

- Kline, David, etc.. (2005). Blog!: How the Newest Media Revolution is Changing Politics, Business, and Culture. ISBN 1-59315-141-1

- "Blogging Clicks With Colleges", The Washington Post, Friday, March 11, 2005; Page B01.

- "The 18thc Online: commonplace book or coffeehouse?". Notes from a lecture given at NEASECS by Miriam Jones, Associate Professor of English in the Department of Humanities and Languages at the University of New Brunswick, Saint John, which compares commonplace books to blogs.

External links

- First Line Index of English Verses - includes many lines from commonplace books

- The Poetry of Sight: An Online Commonplace Book

- Richard Katzev's Marks in the Margin: Reflections on Notable ideas from my Commonplace Book

- Cameron Louis, ed. (1980). The Commonplace Book of Robert Reynes of Acle

- Commonplaces as figures of speech

- Extraordinary Commonplaces, New York Review of Books

- Schools in Tudor England ISBN 0-918016-28-2

- Commonplace Books by Prof. Lucia Knoles, Assumption College.

- The Zibaldone da Canal commonplace book

- In the Country of Books: Commonplace Books and Other Readings By Richard Katzev

Categories:- Medieval literature

- Books by type

- Publishing terms

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.