- Codex Marchalianus

-

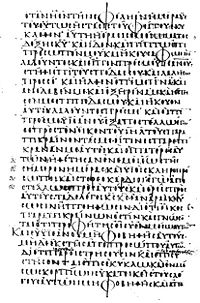

Codex Marchalianus designated by siglum Q is a 6th-century Greek manuscript copy of the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh or Old Testament) known as the Septuagint. The text was written on vellum in uncial letters. Palaeographically it has been assigned to the 6th century.[1]

Its name was derived from a former owner, Rene Marchal.[2]

Contents

Description

The manuscript is in quarto volume, arranged in quires of five sheets or ten leaves each, like Codex Vaticanus or Codex Rossanensis. It contains text of the Twelve Prophets, Book of Isaiah, Book of Jeremiah with Baruch, Lamentations, Epistle, Book of Ezekiel, Book of Daniel, with Susanna and Bel. The order of the 12 Prophets is unusual: Hosea, Amos, Micah, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. The order of books is the same as in Codex Vaticanus.[3][4] The Book of Daniel represents the Theodotion version.[3]

Actually the manuscript consists of 416 parchment leaves, but the first twelve contain patristic matter, and did not form a part of the original manuscript. The leaves measure 11 x 7 inches (29 x 18 cm). The writing is in one column per page, 29 lines per column, and 24-30 letters in line.[4][5] It is written in bold uncial of the so-called Coptic style.[2]

In the first half of the 19th century it had the reputation of being one of the oldest manuscript of Septuagint. It is generally agreed that Codex Marchalianus belongs, to a well-defined textual family with Hesychian characteristics, and its text is a result of the Hesychian recension (along with the manuscripts A, 26, 86, 106, 198, 233).[6][7]

In Book of Isaiah 45:18 where the Greek translator of Septuaginta used εγω ειμι to render "I am YHWH", it was corrected by a later hand to "I am Lord".[8]

The manuscript is used in discussion about the Tetragrammaton.

About seventy items of an onomasticon stand in the margins of Ezekiel and Lamentations.[2]

History of the codex

The manuscript was written in Egypt not later than the 6th century. It seems to have remained there till the ninth, since the uncial corrections and annotations as well text exhibits letters of characteristically Egyptian form. From Egypt it was carried before the 12th century to South Italy, and thence into France, where it became the property of the Abbey of St. Denys near Paris.[3] Rene Marchal (hence name of the codex) obtained the manuscript from the Abbey of St. Denys. From the library of Marchal it passed into the hands of Cardinal Rochefoucauld, who in turn presented it to the College de Clermont, the celebrated Jesuit house in Paris.[2] Finally, in 1785, it was purchased for the Vatican Library, where it now housed.[3][9]

The codex was known for Bernard de Montfaucon and Giuseppe Bianchini. The text of the codex was used by J. Morius, Wettstein, an Montfaucon. It was collated for James Parsons, and edited by Tischendorf in the fourth volume of his Nova Collectio 4 (1869), pp. 225–296,[10] and in the ninth volume of his Nova Collectio 9 (1870), pp. 227–248.[3] Giuseppe Cozza-Luzi edited its text in 1890.[11]

It was suggested by Ceriani in 1890 that the text of the codex represents Hesychian recension; but Hexaplaric signs have been freely added, and the margins supply copious extracts from Aquila, Symmachus, Theodotion, and the Septuaginta of the Hexapla.[4]

The codex is housed in the Vatican Library (Vat. gr. 2125).

See also

References

- ^ Würthwein Ernst (1988). Der Text des Alten Testaments, Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1981, p. 94

- ^ a b c d e Swete, Henry Barclay (1902). An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek. Cambridge. pp. 120.

- ^ a b c Alfred Rahlfs, Verzeichnis der griechischen Handschriften des Alten Testaments, für das Septuaginta-Unternehmen, Göttingen 1914, pp. 273-274.

- ^ Swete, Henry Barclay (1902). An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek. Cambridge. pp. 121.

- ^ The Cambridge History of the Bible (Vol. 2 - The West From the Fathers to the Reformation), ed. by G. W. H. Lampe, Cambridge University Press 2006, p. 19

- ^ Natalio Fernández Marcos, Wilfred G. E. Watson, The Septuagint in context: introduction to the Greek version of the Bible (Brill: Leiden 2000), p. 242

- ^ John T. Townsend, "The Gospel of John and the Jews: The Story of a Religious Divorce", in: Alan T. Davies, ed., Antisemitism and the Foundations of Christianity (Paulist Press, 1979): p. 77

- ^ C. v. Tischendorf, Nova Collectio 4 (1869), p. XIX

- ^ C. v. Tischendorf, Nova Collectio 4 (1869), pp. 225-296

- ^ Giuseppe Cozza-Luzi, Prophetarum codex Graecus Vaticanus 2125 (Romae, 1890)

Further reading

- Constantin von Tischendorf, Nova Collectio 4 (1869), pp. 225–296 [text of the codex]

- Joseph Cozza-Luzi, Prophetarum codex Graecus Vaticanus 2125 (Romae, 1890)

- Antonio Ceriani, De codice Marchaliano seu Vaticano Graeco 2125 (1890)

- Alfred Rahlfs, Verzeichnis der griechischen Handschriften des Alten Testaments, für das Septuaginta-Unternehmen, Göttingen 1914, p. 107-108

- Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1981, Plate 21, p. 94

Categories:- Illuminated biblical manuscripts

- 6th-century biblical manuscripts

- Septuaginta manuscripts

- Vatican Library

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.