- Chromatic polynomial

-

The chromatic polynomial is a polynomial studied in algebraic graph theory, a branch of mathematics. It counts the number of graph colorings as a function of the number of colors and was originally defined by George David Birkhoff to attack the four color problem. It was generalised to the Tutte polynomial by H. Whitney and W. T. Tutte, linking it to the Potts model of statistical physics.

Contents

History

George David Birkhoff introduced the chromatic polynomial in 1912, defining it only for planar graphs, in an attempt to prove the four color theorem. If P(G,k) denotes the number of proper colorings of G with k colors then one could establish the four color theorem by showing P(G,4) > 0 for all planar graphs G. In this way he hoped to apply the powerful tools of analysis and algebra for studying the roots of polynomials to the combinatorial coloring problem.

Hassler Whitney generalised Birkhoff’s polynomial from the planar case to general graphs in 1932. In 1968 Read asked which polynomials are the chromatic polynomials of some graph, a question that remains open, and introduced the concept of chromatically equivalent graphs. Today, chromatic polynomials are one of the central objects of algebraic graph theory[1]

Definition

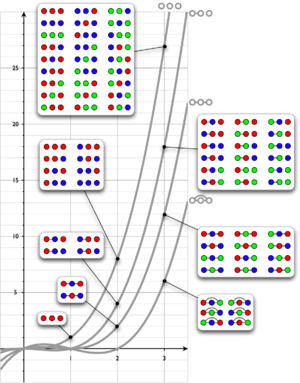

The chromatic polynomial of a graph counts the number of its proper vertex colorings. It is commonly denoted PG(k), χG(k), or πG(k), and sometimes in the form P(G;k), where it is understood that for fixed G the function is a polynomial in k, the number of colors.

For example, the path graph P3 on 3 vertices cannot be colored at all with 0 or 1 colors. With 2 colors, it can be colored in 2 ways. With 3 colors, it can be colored in 12 ways.

Available colors k 0 1 2 3 Number of colorings PG(k) 0 0 2 12 The chromatic polynomial is defined as the unique interpolating polynomial of degree n through the points (k,PG(k)) for k = 0,1,...,n, where n is the number of vertices in G. For the example graph, PG(k) = k(k − 1)2, and indeed PG(3) = 12.

The chromatic polynomial includes at least as much information about the colorability of G as does the chromatic number. Indeed, the chromatic number is the smallest positive integer that is not a root of the chromatic polynomial,

- χ(G) = min{k:PG(k) > 0}.

Examples

Chromatic polynomials for certain graphs Triangle K3 t(t − 1)(t − 2) Path graph Pn t(t − 1)n − 1 Complete graph Kn t(t − 1)(t − 2)...(t − (n − 1)) Tree with n vertices t(t − 1)n − 1 Cycle Cn (t − 1)n + ( − 1)n(t − 1) Petersen graph t(t − 1)(t − 2)(t7 − 12t6 + 67t5 − 230t4 + 529t3 − 814t2 + 775t − 352) Properties

For fixed G on n vertices, the chromatic polynomial P(G,t) is in fact a polynomial; it has degree n. Nonisomorphic graphs may have the same chromatic polynomial. By definition, evaluating the chromatic polynomial in P(G,k) yields the number of k-colorings of G for k = 0,1,2,…,n. Perhaps surprisingly, the same holds for any

, and besides, ( − 1) | V(G) | P(G, − 1) yields the number of acyclic orientations of G.[2] Furthermore, the derivative evaluated at 1, P'(G,1) equals the chromatic invariant θ(G) up to sign.

, and besides, ( − 1) | V(G) | P(G, − 1) yields the number of acyclic orientations of G.[2] Furthermore, the derivative evaluated at 1, P'(G,1) equals the chromatic invariant θ(G) up to sign.If G has n vertices, m edges, and k components G1,G2,…,Gk, then

- The coefficient of tn in P(G,t) is 1.

- The coefficient of tn − 1 in P(G,t) is − m.

- The coefficients of

are all zero.

are all zero. - The coefficient of tk is nonzero.

- The coefficients of every chromatic polynomial alternate in signs.

A graph G with n vertices is a tree if and only if P(G,t) = t(t − 1)n − 1.

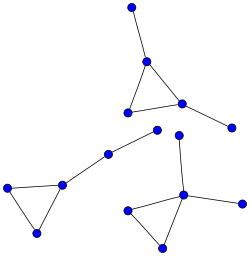

Chromatic equivalence

Two graphs are said to be chromatically equivalent if they have the same chromatic polynomial. Isomorphic graphs have the same chromatic polynomial, but nonisomorphic graphs can be chromatically equivalent. For example, all trees on n vertices have the same chromatic polynomial; in particular, (x − 1)3x is the chromatic polynomial of both the claw graph and the path graph on 4 vertices.

Chromatic uniqueness

A graph is chromatically unique if it is determined by its chromatic polynomial, up to isomorphism. In other words, G is chromatically unique if PG = PH implies that G and H are isomorphic. All Cycle graphs are chromatically unique.[3]

Chromatic roots

A root (or zero) of a chromatic polynomial, called a “chromatic root”, is a value x where PG(x) = 0. Chromatic roots have been very well studied, in fact, Birkhoff’s original motivation for defining the chromatic polynomial was to show that for planar graphs, PG(x) > 0 for x ≥ 4. This would have established the four color theorem.

No graph can be 0-colored, so 0 is always a chromatic root. Only edgeless graphs can be 1-colored, so 1 is a chromatic root for every graph with at least an edge. On the other hand, except for these two points, no graph can have a chromatic root at a real number smaller than or equal to 32/27. A result of Tutte connects the golden ratio ϕ with the study of chromatic roots, showing that chromatic roots exist very close to ϕ2: If Gn is a planar triangulation of a sphere then P(Gn,ϕ) ≤ ϕ5 − n. While the real line thus has large parts that contain no chromatic roots for any graph, every point in the complex plane is arbitrarily close to a chromatic root in the sense that there exists an infinite family of graphs whose chromatic roots are dense in the complex plane.[4]

Algorithms

Chromatic polynomial Input Graph G with n vertices. Output Coefficients of PG Running time O(2nnr) for some constant r Complexity #P-hard Reduction from #3SAT #k-colorings Input Graph G with n vertices. Output PG(k) Running time In P for x = 0,1,2. O(1.6262n) for x = 3. Otherwise O(2nnr) for some constant r Complexity #P-hard unless x = 0,1,2 Approximability No FPRAS for x > 2 Computational problems associated with the chromatic polynomial include

- finding the chromatic polynomial PG of a given graph G, for example finding its coefficients

- evaluating PG(k) at a fixed point k for given G. When k is a natural number, this problem is normally viewed as computing the number of k-colorings of a given graph. For example, this includes the problem #3-coloring of counting the number of 3-colorings, a canonical problem in the study of complexity of counting, complete for the counting class #P.

The first problem is more general because if we knew the coefficients of PG we could evaluate it at any point in polynomial time because the degree is n. The difficulty of the second type of problem depends strongly on the value of k and has been intensively studied in computational complexity.

Efficient algorithms

For some basic graph classes, closed formulas for the chromatic polynomial are known. For instance this is true for trees and cliques, as listed in the table above.

Polynomial time algorithms are known for computing the chromatic polynomial for wider classes of graphs, including chordal graphs[5] and graphs of bounded clique-width.[6] The latter class includes cographs and graphs of bounded tree-width, such as outerplanar graphs.

Deletion–contraction

A recursive way of computing the chromatic polynomial is based on edge contraction: for a pair of vertices u and v the graph G / uv is obtained by merging the two vertices and removing any edges between them. Then the chromatic polynomial satisfies the recurrence relation

- P(G,k) = P(G − uv,k) − P(G / uv,k)

where u and v are adjacent vertices and G − uv is the graph with the edge uv removed. Equivalently,

- P(G,k) = P(G + uv,k) + P(G / uv,k)

if u and v are not adjacent and G + uv is the graph with the edge uv added. In the first form, the recurrence terminates in a collection of empty graphs. In the second form, it terminates in a collection of complete graphs. These recurrences are also called the Fundamental Reduction Theorem[7] Tutte’s curiosity about which other graph properties satisfied such recurrences led him to discover a bivariate generalization of the chromatic polynomial, the Tutte polynomial.

The expressions give rise to a recursive procedure, called the deletion–contraction algorithm, which forms the basis of many algorithms for graph coloring. The ChromaticPolynomial function in the computer algebra system Mathematica uses the second recurrence if the graph is dense, and the first recurrence if the graph is sparse[8] The worst case running time of either formula satisfies the same recurrence relation as the Fibonacci numbers, so in the worst case, the algorithm runs in time within a polynomial factor of

.[9] The analysis can be improved to within a polynomial factor of the number t(G) of spanning trees of the input graph.[10] In practice, branch and bound strategies and graph isomorphism rejection are employed to avoid some recursive calls, the running time depends on the heuristic used to pick the vertex pair.

.[9] The analysis can be improved to within a polynomial factor of the number t(G) of spanning trees of the input graph.[10] In practice, branch and bound strategies and graph isomorphism rejection are employed to avoid some recursive calls, the running time depends on the heuristic used to pick the vertex pair.Computational complexity

The problem of computing the number of 3-colorings of a given graph is a canonical example of a #P-complete problem, so the problem of computing the coefficients of the chromatic polynomial is #P-hard. Similarly, evaluating PG(3) for given G is #P-complete. On the other hand, for k = 0,1,2 it is easy to compute PG(k), so the corresponding problems are polynomial-time computable. For integers k > 3 the problem is #P-hard, which is established similar to the case k = 3. In fact, it is known that PG(x) is #P-hard for all x (including negative integers and non-integers) except for the three “easy points”[11] Thus, from the perspective of #P-hardness, the complexity of computing the chromatic polynomial is completely understood.

In the expansion

, the coefficient an is always equal to 1, and several other properties of the coefficients are known. This raises the question if some of the coefficients are easy to compute. However the computational problem of computing the rth coefficient of PG for fixed r for given graph G is hard for #P.[12]

, the coefficient an is always equal to 1, and several other properties of the coefficients are known. This raises the question if some of the coefficients are easy to compute. However the computational problem of computing the rth coefficient of PG for fixed r for given graph G is hard for #P.[12]No approximation algorithms for computing PG(x) are known for any x except for the three easy points. At the integer points

, the corresponding decision problem of deciding if a given graph can be k-colored is NP-hard. Such problems cannot be approximated to any multiplicative factor by a bounded-error probabilistic algorithm unless NP = RP, because any multiplicative approximation would distinguish the values 0 and 1, effectively solving the decision version in bounded-error probabilistic polynomial time. In particular, under the same assumption, this rules out the possibility of a fully polynomial time randomised approximation scheme (FPRAS). For other points, more complicated arguments are needed, and the question is the focus of active research. As of 2008[update], it is known that there is no FPRAS for computing PG(x) for any x > 2 unless NP = RP holds.[13]

, the corresponding decision problem of deciding if a given graph can be k-colored is NP-hard. Such problems cannot be approximated to any multiplicative factor by a bounded-error probabilistic algorithm unless NP = RP, because any multiplicative approximation would distinguish the values 0 and 1, effectively solving the decision version in bounded-error probabilistic polynomial time. In particular, under the same assumption, this rules out the possibility of a fully polynomial time randomised approximation scheme (FPRAS). For other points, more complicated arguments are needed, and the question is the focus of active research. As of 2008[update], it is known that there is no FPRAS for computing PG(x) for any x > 2 unless NP = RP holds.[13]Notes

- ^ Several chapters Biggs (1993)

- ^ Stanley (1973)

- ^ Chao & Whitehead (1978)

- ^ Sokal (2004)

- ^ Naor, Naor & Schaffer (1987).

- ^ Giménez, Hliněný & Noy (2005); Makowsky et al. (2006).

- ^ Dong, Koh & Teo (2006)

- ^ Pemmaraju, Skiena & 2003 (Sect. 7.4.2.)

- ^ Wilf (1986)

- ^ Sekine, Imai & Tani (1995)

- ^ Jaeger, Vertigan & Welsh (1990), based on a reduction in (Linial 1986).

- ^ Oxley & Welsh (2001)

- ^ Goldberg & Jerrum (2008)

References

- Dong, F. M.; Koh, K. M.; Teo, K. L. (2005), Chromatic polynomials and chromaticity of graphs, World Scientific Publishing Company, ISBN 9812563172

- Fomin, F. V.; Gaspers, S.; Saurabh, S. (2007), "Improved Exact Algorithms for Counting 3- and 4-Colorings", Proc. 13th Annual International Computing and Combinatorics Conference (COCOON), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4598, Springer, pp. 65–74

- Giménez, O.; Hliněný, P.; Noy, M. (2005), "Computing the Tutte polynomial on graphs of bounded clique-width", Proc. 31st Int. Worksh. Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science (WG 2005), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3787, Springer-Verlag, pp. 59–68, doi:10.1007/11604686_6

- Goldberg, L.A.; Jerrum, M. (2008), "Inapproximability of the Tutte polynomial", Information and Computation 206 (7): 908, doi:10.1016/j.ic.2008.04.003

- Jaeger, F.; Vertigan, D. L.; Welsh, D. J. A. (1990), "On the computational complexity of the Jones and Tutte polynomials", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 108: 35–53, doi:10.1017/S0305004100068936

- Linial, N. (1986), "Hard enumeration problems in geometry and combinatorics", SIAM J. Algebraic Discrete Methods 7 (2): 331–335, doi:10.1137/0607036

- Makowsky, J. A.; Rotics, U.; Averbouch, I.; Godlin, B. (2006), "Computing graph polynomials on graphs of bounded clique-width", Proc. 32nd Int. Worksh. Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science (WG 2006), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4271, Springer-Verlag, pp. 191–204, doi:10.1007/11917496_18

- Pemmaraju, S.; Skiena, S. (2003), Computational Discrete Mathematics: Combinatorics and Graph Theory with Mathematica, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521806860

- Naor, J.; Naor, M.; Schaffer, A. (1987), "Fast parallel algorithms for chordal graphs", Proc. 19th ACM Symp. Theory of Computing (STOC '87), pp. 355–364, doi:10.1145/28395.28433.

- Sekine, K.; Imai, H.; Tani, S. (1995), "Computing the Tutte polynomial of a graph of moderate size", Algorithms and Computation, 6th International Symposium, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1004, Cairns, Australia, December 4–6, 1995: Springer, pp. 224–233

- Sokal, A. D. (2004), "Chromatic Roots are Dense in the Whole Complex Plane", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing 13 (2): 221–261, doi:10.1017/S0963548303006023

- Stanley, R. P. (1973), "Acyclic orientations of graphs", Disc. Math. 5 (2): 171–178, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(73)90108-8

- Wilf, H. S. (1986), Algorithms and Complexity, Prentice–Hall, ISBN 0130219738

- Timme, M.; van Bussel, F.; Fliegner, D.; Stolzenberg, Sebastian (2009), "Counting complex disordered states by efficient pattern matching: chromatic polynomials and Potts partition functions", New J. Phys. 11 (2): 023001, doi:10.1088/1367-2630/11/2/023001

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Chromatic polynomial" from MathWorld.

- PlanetMath Chromatic polynomial

- Code for computing Tutte, Chromatic and Flow Polynomials by Gary Haggard, David J. Pearce and Gordon Royle: [1]

Categories:- Graph invariants

- Graph coloring

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.