- Chandler v Cape plc

-

Chandler v Cape plc

Court High Court Citation(s) [2011] EWHC 951 (QB) Case opinions Wyn Williams J Keywords Tort victim, asbestos, duty of care, corporate veil, subsidiary Chandler v Cape plc [2011] EWHC 951 (QB) is a UK company law and English tort law case concerning the availability of damages for a tort victim from a parent company, when the victim is harmed by the operations of a subsidiary company.

Contents

Facts

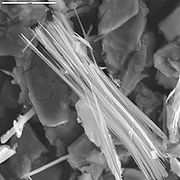

David Chandler had been employed by a wholly owned subsidiary company of Cape plc from 1959 to 1962. Cape plc manufactured asbestos. In 2007 Mr Chandler discovered he had asbestosis, however the subsidiary of Cape plc no longer existed, and it had no policy of insurance. Mr Chandler brought a claim against Cape plc alleging it should be jointly and severably liable to pay him damages. Cape plc contended it owed no duty of care to the employees of its subsidiaries.

Judgment

Wyn Williams J held that Cape plc owed Mr Chandler a duty of care, as the threefold test of foreseeability, proximity and it being fair, just and reasonable, was met according to Caparo Industries Plc v Dickman.[1] Cape plc had had actual knowledge of the subsidiary employees' working conditions, and the asbestos risk was obvious. It had employed a scientific and medical officer to be responsible for health and safety issues, and Cape plc retained responsibility for ensuring its own employees, and those of subsidiaries were not harmed. Hence there was sufficient proximity, and a duty of care arose.

“ 48 In the light of the contemporaneous and later documents discussed above there can be little doubt that the Defendant exercised control over some of the activities of Cape Products from the time that it came into existence and through the period during which the Claimant was one of its employees. With his usual realism, Mr Feeny does not seek to argue to the contrary. He submits, however, that although the Defendant was obviously entitled to exercise control over Cape Products and from time to time it did so, that does not mean that the Defendant controlled all its important activities. I accept that submission. A glance at the minutes of the meetings of the directors of Cape Products in the period 1956 to 1962 shows that many decisions about its activities, some of them important, were taken without reference to the Defendant. 49 It does not seem to me, however, that the Claimant's case stands or falls simply upon whether he can establish that the Defendant controlled all the activities of Cape Products. It is enough, in my judgment, if he can establish that the Defendant either controlled or took overall responsibility for the measures adopted by Cape Products to protect its employees against harm from asbestos exposure. I will explain why in the next section of my judgment.

[...]

64 In Caparo Industries Plc v Dickman [1992] 2 A.C. 605 Lord Bridge summarised the test which is to be applied in determining whether or not a person owes a duty of care to another. He said this:

“What emerges is that, in addition to the foreseeability of damage, necessary ingredients in any situation giving rise to a duty of care are that there should exist between the party owing the duty and the party to whom it is owed a relationship characterised by the law as one of ‘proximity’ or ‘neighbourhood’ and that the situation should be one in which the court considers it fair, just and reasonable that the law should impose a duty of a given scope on the one party for the benefit of the other.”

65 Subsequently, this formulation has come to be known as the “three-stage test” for determining whether or not a duty situation exists. Essentially, my task is to apply that test to the facts of this case.

66 Before doing so, however, it is necessary to dispel certain possible misunderstandings which might arise in cases of this type or upon a cursory reading of this judgment. First, the fact that the Claimant was owed a duty of care by Cape Products does not prevent such a duty arising between the Claimant and other parties. No doubt, the fact that a duty situation exists between the Claimant and his employer is a factor to be taken into account when deciding whether another party owes the Claimant such a duty. But, to repeat, the existence of the duty between the Claimant and his employer cannot preclude another person being fixed with a duty of care. Second, the fact that Cape Products was a subsidiary of the Defendant or part of a group of companies of which the Defendant was the parent cannot mean by itself that the Defendant owes a duty to the employees of Cape Products. So much is clear from Adams and others v Cape Industries plc & another [1991] 1 AER 929 . Equally, the fact that Cape Products was a separate legal entity from the Defendant cannot preclude the duty arising. Third, this case has not been presented on the basis that Cape Products was a sham – nothing more than a veil for the activities of the Defendant. Accordingly, this is not a case in which it would be appropriate to “pierce the corporate veil.”

67 It is commonly the case that injured workmen suffer their injuries as a consequence of the negligent acts or omissions of more than one legally identifiable party. That was the alleged situation in the case of Connelly v The Ritz Corporation Plc and another QBD 4/12/1998 , a decision much relied upon by Mr Weir QC. In Connelly the Claimant was employed by a Namibian company called Rossing Uranium Ltd to work in an open-cast uranium mine in Namibia. Rossing Uranium Ltd was a Namibian subsidiary of The Ritz Corporation Plc. As a consequence of his work in Namibia the Claimant developed squamous-cell carcinoma of the larynx. He brought proceedings in this country for damages against The Ritz Corporation Plc and another English company which was a wholly owned subsidiary of Ritz in even though his exposure had occurred in Namibia and, no doubt, a duty of care was owed to him by his employer.

68 The Defendant's response was to seek to strike out the claim. It did so on a number of grounds but one of the grounds relied upon was that the pleaded case did not support the existence of the alleged duty of care on the part of the Defendants. During the course of his judgment Wright J summarised the Defendants' arguments as follows:—

“Mr Spencer QC on behalf of the Defendant argues that this pleading whether in its amended or re-amended form, discloses no cause of action. In particular, he says, it lays no foundation for the alleged duty of care said to be owed to the plaintiff. He points out, as is undoubtedly the case, that it is not alleged that the plaintiff was employed by either of the First or Second Defendants…he points out, and it is not contended otherwise, that a duty of care to the plaintiff, as a Rossing employee, cannot come into existence simply because the employing company is a subsidiary (whether wholly owned or not) of a parent company which it is sought to fix with such a duty. Nor, as he points out, does the pleading seek to set out any of the relatively limited circumstances under which the doctrine of “piercing the corporate veil” can be invoked. There is no suggestion on the face of the pleading that Rossing was anything other than a separate and independent company, registered in Namibia, having its own separate Board of Directors – even if some of those directors may also have been the directors of the parent company. Accordingly, says Mr Spencer, unless it is being alleged that Rossing was a bogus or “sham” company with no separate will of its own, but is simply doing the bidding of one or other of its parent companies in England, the pleading sets up no factual basis for the duty alleged to have been owed by the English companies to the plaintiff. Mr Spencer asserts that no other person other than the plaintiff's actual employer can owe the duty owed by a master to his servant to the plaintiff.”

69 Wright J's answer to these submissions was given in the section of his judgment which followed immediately:—

“As a matter of strict language this may well be true; but that is not to say that in appropriate circumstances there may not be some other person or persons who owe a duty of care to an individual plaintiff which may be very close to the duty owed by a master to his servant. For example, the consultant who advises the employer upon the safety of his work processes may owe a duty to the individual employee who he can foresee may be affected by the contents of that advice – see, for example, Clay v Crump & Sons Ltd [1964] 1 QB 533 . Even more clearly, if the situation is that an employer has entirely handed over responsibility for devising, installing and operating the various safety precautions required of an employer to an independent contractor, then that contractor may owe a duty to the individual employee which is virtually coterminous with that of the employer himself. That is not to say that the employer, by so handing over such responsibility, will necessarily escape his own liability to his employee. On a fair reading of his pleading, it seems to me that that is more or less what the amended Statement of Claim alleges – namely, that the first Defendant had taken into its own hands the responsibility for devising an appropriate policy for health and safety to be operated at the Rossing mine, and that either the first Defendant or one or other of its English subsidiaries implemented that policy and supervised the precautions necessary to ensure as so far as was reasonably possible, the health and safety of the Rossing employees through the RTZ supervisors. Such an allegation, if true, seems to me to impose a duty of care on those Defendants who undertook those responsibilities, whatever contribution Rossing itself may have made towards the safety procedures at the mine. The situation would be an unusual one; but if the pleading represents the actuality then, as it seems to me, the situation is likely to comprehend the elements of proximity, foreseeability and reasonableness required to give rise to a duty of care: Caparo Industries v Dickman [1992] 2 A.C. 605 .”

70 Mr Feeny acknowledges the possibility that the Defendant could assume a duty to the Claimant; he submits, however, that there can be no general duty upon the Defendant to prevent an independent third party from causing harm to the Claimant. Mr Feeny submits that special or exceptional circumstances needed to exist before a duty could be imposed upon the Defendant to prevent harm to him from asbestos exposure which was caused by the negligence and/or breach of statutory duty of Cape Products.

71 It is true that generally the law imposes no duty upon a party to prevent a third party from causing damage to another. That emerges clearly from Smith v Littlewoods Organisation Ltd [1987] A.C. 241 . However, that same case makes it clear that there are exceptions to the general rule. In his speech Lord Goff identified the circumstances in which a duty might arise. They were a) where there was a special relationship between the Defendant and Claimant based on an assumption of responsibility by the Defendant; b) where there is a special relationship between the Defendant and the third party based on control by the Defendant; c) where the Defendant is responsible for a state of danger which may be exploited by a third party; and d) where the Defendant is responsible for property which may be used by a third party to cause damage. Mr Weir QC submits that if it is necessary to show that special or exceptional circumstances exist in the instant case that can be done. He submits that there was a special relationship between the Defendant and the Claimant based upon the Defendant's assumption of responsibility for safeguarding the Claimant against illness from exposure to asbestos; alternatively, the Defendant had the ultimate control of those measures which were taken to protect the Claimant from the risk of exposure to asbestos.

72 I end my discussion of the parties' submissions upon the law where I began. I must apply the three-stage test in Caparo. I must do so in the factual context that I have outlined in the preceding section of this judgment.

73 On the basis of the evidence adduced before me I am satisfied that the Defendant had actual knowledge of the Claimant's working conditions. As I have said the Defendant produced Asbestolux at the Uxbridge factory until 1956. There is no basis for concluding that production practices changed in any significant way before or during the Claimant's period of employment. In particular, as is clear, Asbestolux was produced in a building which had no sides. Dust was permitted to escape without any real regard for the consequences. This was no failure in day-to-management; this was a systemic failure of which the Defendant was fully aware.

74 The risk of an asbestos related disease from exposure to asbestos dust was obvious. Mr Feeny does not suggest otherwise. There can be no doubt that the Defendant should have foreseen the risk of injury to the Claimant. As I have said that is admitted.

75 The Defendant employed a scientific officer and a medical officer who were responsible, between them, for health and safety issues relating to all the employees within the group of companies of which the Defendant was parent. On the basis of the evidence as a whole it was the Defendant, not the individual subsidiary companies, which dictated policy in relation to health and safety issues insofar as the Defendant's core business impacted upon health and safety. The Defendant retained responsibility for ensuring that its own employees and those of its subsidiaries were not exposed to the risk of harm through exposure to asbestos. In reaching that conclusion I do not intend to imply that the subsidiaries, themselves, had no part to play – certainly in the implementation of relevant policy. However, the evidence persuades me that the Defendant retained overall responsibility. At any stage it could have intervened and Cape Products would have bowed to its intervention. On that basis, in my judgment, the Claimant has established a sufficient degree of proximity between the Defendant and himself. At paragraph 27 of the skeleton argument submitted on behalf of the Claimant the suggestion is made that in this case the degree of proximity between the Defendant and Claimant is central to the analysis of whether, on the facts, a duty of care was owed. I agree. The facts I have found proved in this case persuade me that proximity is established.

76 No argument was advanced to me by Mr Feeny that if foreseeability and proximity were established nonetheless it was not fair, just and reasonable for a duty to exist. Had such an argument been advanced I would have rejected it. By the late 1950s it was clear to the Defendant that exposure to asbestos brought with it very significant risk of very damaging and life threatening illness. I can think of no basis upon which it would be proper to conclude in those circumstances that it would not be just or reasonable to impose a duty of care upon an organisation like the Defendant.

77 In my judgment the three-stage test for the imposition of a duty of care is satisfied in this case. Accordingly, the Claimant succeeds in his claim. Conclusion

78 I propose to enter judgment for the Claimant for an award of provisional damages. For the avoidance of any doubt about its terms it would assist if the parties submitted a draft of the order for my approval prior to or at the handing down of the judgment. There need be no attendance at the handing down if an order consequent upon this judgment can be agreed by the parties.

” See also

Corporate personality cases Case of Sutton's Hospital (1612) 77 ER 960Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22Macaura v Northern Assurance Co Ltd [1925] AC 619Gilford Motor Co Ltd v Horne [1933] Ch 935Lee v Lee’s Air Farming [1961] AC 12Jones v Lipman [1962] 1 WLR 832Wallersteiner v Moir [1974] 1 WLR 991DHN Ltd v Tower Hamlets LBC [1976] 1 WLR 852Woolfson v Strathclyde Regional Council [1978] UKHL 5Adams v Cape Industries plc [1990] Ch 433Lubbe v Cape Plc [2000] UKHL 41Chandler v Cape plc [2011] EWHC 951 (QB)Notes

- ^ [1990] 2 AC 605

References

External links

Categories:- United Kingdom company case law

- English tort case law

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.