- Henry Maudslay

-

Henry Maudslay

Portrait by Pierre Louis ('Henri') Grevedon 1827Born 22 August 1771 Died 14 February 1831 Nationality British Work Significant advance machine tool technology Henry Maudslay (pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was a British machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology.

Contents

Early life

Maudslay's father, also named Henry, served as a wheelwright in the Royal Engineers. After being wounded in action he became a storekeeper at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, London.[when?] There he married a young widow, Margaret Laundy and they had seven children, among which young Henry was the fifth. Henry’s father died in 1780. Henry began filling cartridges at the Arsenal when he was twelve. After two years, he was transferred to a carpenter’s shop followed by a blacksmith’s forge, where at the age of fifteen he began training as a blacksmith. He seems to have specialised in the lighter, more complex kind of forge work.[1]

Bramah lock

Maudslay acquired such a good reputation for his skill that Joseph Bramah (the inventor of the hydraulic press) called for his services. Bramah had recently designed and patented an improved type of lock based on the tumbler principle, but was having difficulty manufacturing the complex lock at an economic price. Having sent for Maudslay on the recommendation of one of his employees, Bramah was surprised to discover that he was only eighteen, but Maudslay demonstrated his ability and started work at Bramah’s workshop in Denmark Street, St Giles. It was Maudslay who built the lock that was displayed in Bramah’s shop window with a notice offering a reward of 200 guineas to anyone who could pick it. It resisted all efforts for forty-seven years. Maudslay designed and made a set of special tools and machines that allowed the lock to be made at an economic price.[1]

Hydraulic press

Bramah had designed a hydraulic press, but was having problems sealing both the piston and the piston rod where it fitted into the cylinder. The usual method was hemp packing but the pressures were too high for this to work. Maudslay came up with the idea of a leather cup washer, which gave a perfect seal but offered no resistance to movement when the pressure was released. The new hydraulic press worked perfectly thereafter. But Maudslay, who had made a major contribution to its success, received little credit for it.[1]

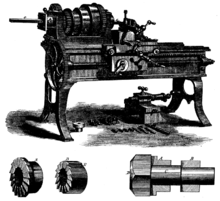

Slide-rest lathe

At the time when Maudslay began working for Bramah, the typical lathe was worked by a treadle and the workman held the cutting tool against the work. This did not allow for precision, especially in cutting iron. Maudslay designed a tool holder into which the cutting tool would be clamped, and which would slide on accurately planed surfaces to allow the cutting tool to move in either direction. This meant that machine components could be turned out reproducibly and precisely. Maudslay’s slide-rest lathe revolutionised the production of machine components.[1]

Promotion and marriage

Maudslay had shown himself to be so talented that he was soon made manager of Bramah’s workshop. In 1791 he married Bramah’s housemaid, Sarah Tindel. The couple were to have four sons together. Thomas Henry, the eldest, and Joseph, the youngest, subsequently joined their father in business. William, the second, became a civil engineer, being one of the founders of the Institute of Civil Engineers.

In 1797, after having worked for Bramah for eight years, Maudslay asked for an increase in his wage of only 30s a week. Bramah refused his request. This refusal determined Maudslay to set up business on his own account.[1]

His own business

Maudslay obtained a small shop and smithy in Wells Street, off Oxford Street. In 1800, Maudslay moved to larger premises in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square.

Following earlier work by Samuel Bentham, his first major commission was to build a series of 42 woodworking machines to produce wooden rigging blocks (each ship required thousands) for the Navy under Sir Marc Isambard Brunel. The machines were installed in the purpose-built Portsmouth Block Mills, which still survive, including some of the original machinery. The machines were capable of making 130,000 ships’ blocks a year, needing only ten unskilled men to operate them compared with the 110 skilled workers needed before their installation.[3] This was the first well-known example of specialized machinery, used for machining in an assembly-line type factory.[1][4][5]

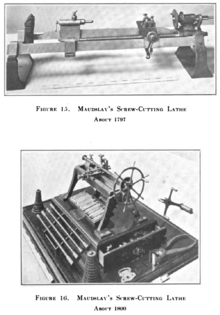

Screw cutting

Maudslay also developed the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe in 1800, allowing standardisation of screw thread sizes for the first time. This allowed the concept of interchangeability (an idea that was already taking hold) to be practically applied to nuts and bolts. Before this, all nuts and bolts had had to be made as matching pairs only. This meant that when machines were disassembled, careful account had to be kept of the matching nuts and bolts in preparation for reassembly. Maudslay standardized the screw threads used in his workshop and produced sets of taps and dies that would make nuts and bolts consistently to those standards, so that any bolt of the appropriate size would fit any nut of the same size. This was a major advance in workshop technology.[1]

Lathe design

Although Maudslay was not the first person to invent a slide-rest (as many writers have claimed),[6] and may not have been the first inventor to combine a lead screw, slide-rest, and set of change gears all on one lathe (Jesse Ramsden may have done that in 1775; evidence is scant),[7] he is certainly the person who introduced to the rest of the world the winning three-part combination of lead screw, slide rest, and change gears, sparking a great advance in machine tools and in the engineering use of screw threads.

Maudslay invented the first bench micrometer capable of measuring to one ten-thousandth of an inch (0.0001 in ≈ 3 µm). He called it the "Lord Chancellor", as it was used to settle any questions regarding accuracy of workmanship.

By 1810 Maudslay was employing eighty workers and was running out of room at his workshop, so he moved to larger premises in Westminster Road, Lambeth. Maudslay also recruited a promising young Admiralty draughtsman, Joshua Field, who proved to be so talented that Maudslay took him into partnership. The company later became Maudslay, Sons & Field, when Maudslay’s sons became partners.[1]

Marine engines

Maudslay’s Lambeth works began to specialize in the production of marine steam engines. The type of engine he used for ships was a side-lever design, in which a beam was mounted alongside the cylinder. This saved on height in the cramped engine rooms of steamers. His first marine engine was built in 1815, of 17 h.p., and fitted to a Thames steamer called Richmond. In 1823 a Maudslay engine powered the Lightning, the first steam-powered vessel to be commissioned by the Royal Navy. In 1829 a side-lever engine of 400 h.p. was completed for HMS Dee, and was the largest marine engine existing at that time.

The marine engine works became a partnership between Maudslay, his son Joseph, and Joshua Field, as Maudslay, Sons and Field.

In 1838, after Maudslay's death, the Lambeth works supplied a 750 h.p. engine for Isambard Kingdom Brunel's famous SS Great Western, the first transatlantic steamship. They patented a double cylinder direct acting engine in 1839. They introduced some of the earliest screw propulsion units for ships, including that for the first Admiralty screw steamship, HMS Rattler, in 1841. By 1850 the firm had supplied more than two hundred vessels with steam engines,[1] though the firm's dominance was being challenged by John Penn's trunk engine design.

Thames Tunnel

In 1825 Marc Isambard Brunel began work on the Thames Tunnel, intended to link Rotherhithe with Wapping. After many difficulties this was successfully completed in 1842, and was the first tunnel under the Thames. The tunnel would not have been possible without the innovative tunneling shield, designed by Marc Brunel and built by Maudslay Sons & Field at their Lambeth works. Maudslay also supplied the steam-driven pumps that were so important in keeping the tunnel workings dry.[8]

Later life

At the end of his life Maudslay developed an interest in astronomy and began to construct a telescope. He intended to buy a house in Norwood and build a private observatory there, but he died before he was able to accomplish his plan. In January 1831 he caught a chill while crossing the English Channel. He was ill for four weeks and died on 15 February. He was buried in the churchyard of St Mary Magdalen Woolwich, and his memorial in its Lady Chapel was designed by himself.[1]

Many outstanding engineers trained in his workshop including Richard Roberts, David Napier, Joseph Clement, Sir Joseph Whitworth, James Nasmyth (inventor of the steam hammer), Joshua Field and William Muir.

Henry Maudslay played his part in the development of mechanical engineering, when it was in its infancy, but he was especially pioneering in the development of machine tools to be used in engineering workshops across the world.

Maudslay’s company was one of the most important British engineering manufactories of the nineteenth century, finally closing in 1904.

Pronunciation and spelling

Maudslay's surname is pronounced with a reduced /li/ terminal syllable (as typical of British pronunciation of such terminals, e.g., /li/, /lɪ/, /lɛ/). Many books have spelled his surname with an "e" as "Maudsley";[9] but this seems to be an error propagated via citation of earlier books containing the same error.

See also

- Henry Maudsley, another 19th-century Englishman, who was a notable psychiatrist

- Maudslay Motor Company, founded by Walter H. Maudslay, great grandson of Henry Maudslay.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rolt, L.T.C., “Great Engineers”, 1962, G. Bell and Sons Ltd, ISBN

- ^ Roe 1916, frontispiece

- ^ Deane 1965, page 131

- ^ Gilbert, K.R. (1965). The Portsmouth Blockmaking Machinery. HMSO, for the Science Museum. pp. 1. "...the first instance of the use of machine tools for mass production."

- ^ Rees, A. (1819). "Machinery". The Cyclopaedia of Arts, Science, and Literature. Vol XXI. London. An entire chapter devoted to the Portsmouth machinery, of 18 pages and 7 plates.

- ^ Roe 1916:36-40.

- ^ Roe 1916:38.

- ^ Bagust, Harold, “The Greater Genius?”, 2006, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0711031754

- ^ A search of Google Books for the query "Henry+Maudsley"+lathe (quotes inclusive) returns several hundred results that clearly are meant to refer to the same identity.

Bibliography

- John Cantrell and Gillian Cookson, eds., Henry Maudslay and the Pioneers of the Machine Age, 2002, Tempus Publishing, Ltd, pb., (ISBN 0-7524-2766-0) This is a collection of essays by various specialists, and comprises biographies of Maudslay, Roberts, Napier, Clement, Whitworth, Nasmyth and Muir, as well as an account of the London Engineering Scene at the time of Maudslay, and an account of the firm from the death of Maudslay in 1831 until its demise in 1904.

- Coad, Jonathan, The Portsmouth Block Mills: Bentham, Brunel and the start of the Royal Navy's Industrial Revolution, 2005, ISBN 1-873592-87-6.

- Deane, Phyllis (1965). The First Industrial Revolution. Cambridge University Press.

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press, LCCN 16-011753, http://books.google.com/books?id=X-EJAAAAIAAJ&printsec=titlepage. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-024075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, IL, USA (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

External links

Categories:- 1771 births

- 1831 deaths

- English inventors

- Steam engine engineers

- English engineers

- British mechanical engineers

- Machine tool builders

- People of the Industrial Revolution

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.