- Nandi people

-

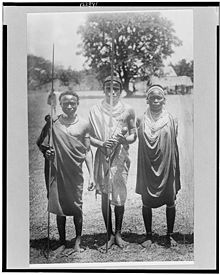

The Nandi people are a number of Kenyan tribes living in the highland areas of the Nandi Hills in Rift Valley Province who speak the Nandi languages. They are a sub-group of the Kalenjin people.

The Nandi live in Nandi County, Uasin-Gishu County, Trans-Nzoia County, Nakuru County and parts of Narok County. Before British colonization, they were sedentary cattle-herders, sometimes also practicing agriculture. Their settlements were more or less evenly distributed rather than being grouped into villages. Like other Nilotic peoples, they were noted warriors. They traditionally practice circumcision of both sexes, although female circumcision is fast fading as a rite of initiation into adulthood. Boys' circumcision festivals took place about every seven and a half years, and boys circumcised at the same time are considered to belong to the same age set; like other Nilotic groups, these age sets (called ibinda, pl. ibinweek) were given names from a limited fixed cycle. Each age set is further subdivided into a subset (siritieet, pl. siritoiik). About four years after this festival, the previous generation officially handed over defense of the country to the newly circumcised youths. Girls' circumcision, excising the clitoris, took place in preparation for marriage.

Contents

Clans (Oreet)

The Nandi peoples have totems or oreet each identified by an 'animal' or tiondo, which no clan member could eat. The identification by Oreet helped prevent inbreeding since marriage within Oreet was largely not permitted. More details are published at Matelong Family Web. Clan symbols (tiondo) range from birds, wild animals, frog and snake to bees. Although the sun is not an animal, 'she' has oreet and is called 'tiondo' in the same sense as a lion. It is claimed that Kong'ony (crested crane) was the first animal allocated a family. Hence Moi (Kong'ony) is regarded as the 'leader' and in child stories this is shown as the source of babies in a family. The jackal (Kimageet, oreet of Tungo, korap oor) is claimed to have been the last tiondo to be allocated and comes along with several rules of favour (ostensibly to hide the fact that it was the last). Hence, even though the Nandi claim 'Cheptaab oreet age ne wendi oreet age' literally 'a daughter from one clan goes to another clan and belongs in the new clan', to mean a woman has no clan, the Tungo girls are permitted to retain their clan identity.

- Kipkenda Maimi

- Segemiat (bee)

- Kiboiis

- Lelwoot

- Solopchoot (coackroach)

- Mooi

- Kong'oony (Crested Crane)

- Soeet (Buffalo)

- Kergeng, Cheptirkiichet (Dik-dik)

- Kipkamoriet

- Kogos, Chepkogosiot (Eagle)

- Kipsirgoi

- Toreet (palee kut ak kutung')

- Kipamui

- Kergeng (Antelope)

- Sogoom

- Chepsirereet (Eagle)

- Talai

- Ng'etuny, Lion (Kuutwo, Talai Orkoi)

- Ng'etuny, Lion (Talai Nandi)

- Kipoongoi (che kwees tibiik)

- Taiyweet

- Kibiegen (kap rat setio let)

- Moseet (Monkey)

- Muriat (rat)

- Kipaa (koros)

- Ndareet (Snake)

- Tisiet (Baboon)

- Toiyoi (moriso)

- Ropta (rain)

- Birechik (Safari Ants)

- Kap Oiit

- Beliot, kiramkeel koe mooi (Elephant)

- Kipleng'wet (rabbit)

- Kipasiiso (Kap koluu)

- Asista (Sun)

- Kuchwa

- Mororochet (frog)

- Tungo (korap oor)

- Kimageetiet (Hyena)

- Kiptabkei

- Chereret (vervet monkey)

Age-set (Ibinda)

The Nandi social organisation centres around the age-set, or ibinda. There are seven age-sets (ibinwek) which are rotational, meaning at the end of one ageset new members of that generation are born. The order is roughly as given below. Among the other Kalenjin peoples, an age-set called Korongoro exists. However, among the Nandi, this ageset is extinct. Legend has it that the members of this ibinda were wiped out in war. For fear of a recurrence, the community decided to retire the age-set. Ibinda was given out at initiation and by simple arrangements, there ought to be one ibinda between a father and a son. For example, a Maina cannot beget a Chumo. The Nandi don't consider a woman to have an ageset, hence she can marry any ageset except that in which her father belongs. The Nandi say "ma tinyei ibin gorgo" which means a woman has no ageset.

- Maina

- Chumo

- Sawe

- Kipkoimet

- Korongoro (not in Nandi)

- Kaplelach

- Kipnyigei

- Nyongi

- Maina

Age sub-set (siritiet)

In each age-set, the initiates were bundled into siritiet or what can be understood as a 'team'. There are four 'teams' or siritoik in an age-set (ibinda) namely:

- Chongin

- Kiptaito

- Tetagaat (literally cow's neck)

- Kiptoinik (literally young calves)

Religion

They traditionally worshiped a supreme deity, Asis (literally "Sun"), as well as venerating the spirits of ancestors. Their land is divided into six "counties" (emet): Wareng in the north, Mosop in the east, Soiin/Pelkut in the south, Aldai and Chesumei in the west, and Em-gwen in the center. The Orkoiyot, or medicine man, was traditionally acknowledged as an overall leader. The Orgoiyot led not only in spiritual matters but also during wars, as evidenced during the war between the British colonials building the railway and the Nandi warriors. The leader at that time was Koitalel Arap Samoei who was killed by Richard Meinertzhagen, a British soldier. In pre-colonial times, they also enjoyed a fearsome reputation as fighters; Arab slave-traders and ivory-traders took care to avoid the area, and the few that dared attempt to traverse it were killed.

Social organisation

The Nandi have had a well structured 'political' system revolving around what might be referred to at the Nandi Bororiet. No other Kalenjin community organised themselves in the Bororiet (pl. bororiosiek) system. The Nandi political life was ordered around 'bororiet' which is distinctly different from oreet (clan) but is probably an expanded form of the advanced order of the 'kokwet' or village system. As explained earlier, people of the same oreet were not necessarily restricted to one bororiet. However, some families were advised, perhaps to avoid recurrent catastrophes, not to live in certain bororiet. A case in point is the long-standing banning of Kap Matelong (and all Kipkenda?) from inhabiting Chesumei which is populated by the relatively obscure but conservative borioriosiek of Cheptol, Kapno and Tibingot.

The Nandi bororiet may be taken as a 'primitive' (not intended to offend, but purely for lack of a better word) model of multipartyism. For it was largely around one's bororiet that vexing, bethrotals and circumcission ceremony attendance were based. It might sound alien to the reader that competition among bororiosiek was more intense than among oratinwek. It would seem, therefore, that with the advent of christianity and the consequential thinking that what was traditional was backward, the disappearance of bororiet became inevitable. The recent resurgence of Nandi nationalism has brought to the fore the social tenets and socio-cultural-political organisational strata. Among these are the realisation that the current level of complacency, laziness and pedestrian attitude to life that is prevalent among the youth has been inspired by a lack of cementing social identities like the bororiet system. Was bororiet, then, a form of a political system? Hence, could we safely albeit without provoking a sense of unjustified pride, say that the bororiosiek were actually a system akin to the modern day multi-party system?

People could and still change bororiet, due to migration, without necessarily changing their oreet. This is where I consider bororiet as a form of a political party. For example, if one's family lived in one bororiet but was haunted by repetitive deaths that pointed to a curse, a ceremony reminiscent of 'Kap Kiyai' was performed to allow the family to change their bororiet by 'crossing a river' in the context of 'ma yaitoos miat aino' which literally means that death does not cross a river (body of water). This elaborate ceremony was called 'raret' (rar means trim or cut off). If you find a family with a name Kirorei then you probably have a family case of bororiet change which came about as a result of 'rareet' (chopping off). People changed bororiet as a result of migration to another koreet, emeet (region). This seems common for some bororiosiek and not others, however. For example an individual who moved to Kabooch could retain the unique identity, leading perhaps derogatively, to the reference of skin rashes that develop on kids heads as 'Kaboochek'. This was understood to mean that the rashes did not infect and blanket the whole head but developed in isolated but closely related colonies! The Matelong family, originally of KapSile, changed their bororiet because of a calamity which has been discussed elsewhere in this blog.

Another instance of change of bororiet is a shameful perhaps spiteful defection 'martaet' which means somebody deserts his bororiet for another. This brings to mind names such as Kimarta. Within each Bororiet were siritoik or sub-bororiet.

Nandi major bororiosiek

- Kap Chepkendi

- Chebolool

- Sigilaiyekab arap Kerebei

- Chebiriir Katuut

- Muruto (Kap lolo)

- Kap Meliilo (mi kericheek ma, gotab ndasimiet)

- Kap Taalam (Che loklokianu ak gariik, che bo ma ki kiop ko somok, che bo arap Kuna)

- Kabooch

- Cheboing'ong ak lelwek

- Kosach nyiim kot koles

- Kaptumoiis

Nandi minor bororiosiek

- Koilegei (che ki sal Tabolwa, Che bo arap Maleel)

- Kabianga

- Kapsile

- Kapno

- Cheptol

- Tibingot (Tebee ng'ot?)

- Murkaptuk

The Nandi athletes

The Nandi people are pioneer athletes in Kenya. From this community have come great distance athletes like the legendary Kipchoge Keino (Kip Keino), a gold medalist at Mexico (1968) and Munich (1972) Olympic games and Prof. Mike Boit, a Bronze medalist at Munich 1972 Olympics. Others include Peter Koech, Bernard Kipchirchir Lagat who represents the USA and Wilson Kipketer who ran for his adopted home of Denmark. Current world beating athletes like Pamela Jelimo, Richard Mateelong, Wilfred Bungei, Janeth Chepkosgei and Super Henry Rono, United Nations Goodwill Ambassador Peter Rono, Tecla Chemabwai, Kenya Paralympian Henry Kirwa among others are Nandi. The father of Kenyan Steeplechasers Amos Kipwambok Biwott comes from the community.

Nandi academics

The Nandi have also produced great scientists and academics like Prof. David Kimutai Some of Moi University, Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Paul Ndalut of Chemistry and Biochemistry department at Moi University, Dr Seronei Chelulei Cheison of the Technical University of Munich, Germany, DR Fredrick Sawe( Director Walterreed, Owner-Nursing home Kericho), DR Saisi Mayo( Dean College of Engineering, Moi University), and Prof. Chelagat Lelei and Prof. Isaack Kosgey, the Dean of the Faculty of Agriculture at Egerton University among others. Prof Mengich(Moi Referral Hospital) Among the leading lawyers from the community are Lawyer Paul Birech of Eldoret, Lawyer Paul Lilan of Nairobi, Lawyer Julius Kipkosgey Kemboy of Nairobi and retired judge Barabara Tanui. Among the leading medics from Nandi are Dr.med. Elly Kibet Cherwon of Heidelberg, Germany, one of very few Africans practising medicine in Germany. Elly also deputises the head of the hospital. There is also Dr. Kirongo (Psychiatrist Moi Referral Hospital),Dr Geoffrey Kiprotich Yebei Ngeny MD (Geriatric Medicine-Internal Medicine) of Pittsburg University, Dr Andrew Kibet Cheruiyot (Consultant Trauma KNH), Dr Franklin Rono.

Nandi politicians

The Nandi people have had remarkable political figures like Jean-Marie Seroney, the first MP for Nandi and Tindiret, Henry Kosgey, Samwel Ngeny, Kipruto Kirwa, Stanley Metto and Ezekiel Barng'etuny, Dr Joseph Misoy and William Morogo Saina. Philomena Chelagat Mutai cut her teeth as a university student in the 1970s and remains one of the most celebrated of Nandi female political leaders.

Society and culture

Female-female marriages within the Nandi culture have been reported[citation needed], although it is unclear if they are still practiced, and only about three percent of Nandi marriages are female-female[citation needed]. Female-female marriages are a socially-approved way for a woman to take over the social and economic roles of a husband and father. They were allowed only in cases where a woman either had no children of her own, had daughters only (one of them could be "retained" at home) or her daughter(s) had married off. The system was practiced "to keep the fire"—in other words, to sustain the family lineage, or patriline, and was a way to work around the problem of infertility or a lack of male heirs. A woman who married another woman for this purpose had to undergo an "inversion" ceremony to "change" into a man. This biological woman, now socially male, became a "husband" to a younger female and a "father" to the younger woman's children, and had to provide a bride price to her wife's family. She was expected to renounce her female duties (such as housework), and take on the obligations of a husband; additionally, she was allowed the social privileges accorded to men, such as attending the private male circumcision ceremonies. No sexual relations were permitted between the female husband and her new wife (nor between the female husband and her old husband); rather, the female husband chose a male consort for the new wife so she will be able to bear children. The wife's children considered the female husband to be their father, not the biological father, because she (or "he") was the socially designated father.

See also

- Rulers of the Nandi

- Terik people

References

Bibliography

- A. C. Hollis. The Nandi: Their Language and Folklore. Clarendon Press: Oxford 1909.

- Ember and Ember. Cultural Anthropology. Pearson Prentice Hall Press: New Jersey 2007.

External links

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.