- Pygmy madtom

-

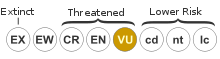

Pygmy madtom Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Actinopterygii Order: Siluriformes Family: Ictaluridae Genus: Noturus Species: N. stanauli Binomial name Noturus stanauli

Etnier & Jenkins, 1980The pygmy madtom (Noturus stanauli) is a species of fish in the Ictaluridae family. It is endemic to the United States.

Contents

Abstract

This species is endemic worldwide to only two known regions of Tennessee. Portions of the Duck, and Clinch Rivers support the only known populations of this federally endangered species. Madtoms are the smallest members of the catfish family. Members of the genus Noturus can be distinguished by their small size, unusually long adipose fin and rounded caudal fin.

Most specimens have been collected over shallow, fine gravel shoals with moderate to swift flow, usually near the stream bank.

A management plan was drafted 27-Sept-94 by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (lead office: Cookeville Ecological Services Field) outlining description of actions to be taken, time frame, responsible parties, labor type and various other activities relating to species repopulation is available on the USFWS website at the following address: http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=E03T.

Geographic Distribution of Species

The Pygmy Madtom has an extremely limited distribution, appearing only in samples taken from the Duck River, in Humphreys and Hickman Counties, Tennessee; and from the Clinch River, Hancock County, Tennessee. These two locations are separated by approximately 600 river miles, though there is no current evidence indicating the entire historical range of the species.

Ecology

The pygmy madtom (Noturus stanauli) is the smallest of madtoms, reaching only about 50 millimeters in length at adulthood. Noturus stanauli are dark brown dorsally and nearly white ventrally. The Pygmy Madtom is similar to the Least Madtom but is distinguished by its white snout and large teeth on the front edge of the pectoral spine. The caudal fin has a dark band or dusky blotches in the middle. The anal fin has 14-17 rays.

N. Stanauli has currently been observed and collected in moderate to swift gravel runs of clear medium-sized rivers in pea-sized gravel of fine sand substrates. Although there are no observations of seasonal habitat shifts, the closely related Smoky Madtom is known to switch from riffles to overwinter in shallow pools (Dinkins 1984). Two closely related species, Noturus baileyi (Smoky Madtom) and N. flavipinnis (Yellowfin Madtom),are found in the flowing portions of pools during the reproductive season (Dinkins and Shute 1993).

Many Specific biological traits of this madtom have not been gathered to date, mainly stemming from a lack of observable specimens in their natural environment. A total of 10 individuals have been found from both locations since the species was listed as endangered in 1993. C.F.I. (Conservation Fisheries, Inc.) of Knoxville, Tennessee was able to propagate young on several instances and reported adult activity was limited only to the early evening hours. Because of this observation, it is believed that the adults are crepuscular.

Madtoms almost exclusively prey on aquatic insect larvae. Most authors have suggested that they are primarily opportunistic feeder and take prey items in proportion to their abundance (Starnes and Starnes 1985, Gutowski and Stauffer 1990).

Related madtoms nest in cavities beneath slabrocks and at times use other cover objects, such as cans and bottles. As native mussels are abundant in pygmy madtom habitat, it is possible that this species might use empty mussel shells for nesting cover. Reproduction likely occurs from spring to early summer.

Management

The Pygmy Madtom was listed as federally endangered throughout the entirety of its range on 27-April-93. As a result, a management plan was drafted 27-Sept-94 by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (lead office: Cookeville Ecological Services Field) outlining description of actions to be taken, time frame, responsible parties, labor type and various other activities relating to species repopulation.

The two known populations are isolated from each other by impoundments, making recolonization of any extirpated population impossible without human intervention. The absence of natural gene flow among the limited populations of these fishes leaves the long-term genetic viability of these isolated populations in question.

Additionally, several madtom species have, for unexplained reasons, been extirpated from sections of their naturally occurring range. One speculated hypothesis of why this may be states "...in addition to visible habitat degradation be related to their being unable to cope with olfactory 'noise' being added to riverine ecosystems in the form of a wide variety of complex organic chemicals that may occur only in trace amounts (Etnier and Jenkins 1980)." If, as they speculated, madtoms are adversely impacted by increased concentrations of organic chemicals, an increase in the presence of these materials could be a problem for the Pygmy Madtom.

Many species that once existed throughout major portions of the Tennessee River now exist only as isolated remnant populations (Neves and Angermeier 1990), and extirpations and extinctions are predicted (Sheldon 1988, Etnier 1993). The Tennessee River previously supported one of the world's richest assemblages of temperate freshwater river fishes (Starnes and Etnier 1986, Sheldon 1988), but this river is now one of the United States' most severely altered river systems. Most of the main stem of Tennessee River and many of its tributaries are impounded. Over 2,300 river miles, or about 20 percent, of the Tennessee River and its tributaries with drainage areas of 25 square miles (65 km2) or greater are impounded (Tennessee Valley Authority 1971). In addition to the loss of riverine habitat within the impoundment, most impoundments also seriously alter downstream aquatic habitat.

Threats affecting the Pygmy Madtom are increased urbanization, coal mining, toxic chemical spills, siltation, improper pesticide use, and stream bank erosion remain threats to the Pygmy Madtom. Additional threats to the madtom include gravel dredging, water withdrawals, and agricultural practices. None of the threats have been eliminated since the fish was listed; consequently, both the Duck and Clinch River populations remain vulnerable to extirpation. Existing Federal and State laws and regulations are applied to actions conducted within the range of Pygmy Madtom to protect the fish and its habitats. However, due to difficulty in finding the fish in surveys the extent of its habitat is unknown.

Monitoring of the species is difficult due to its scarcity in both abundance and distribution. Given the current state of the population, monitoring techniques must minimize impact to the existing individuals. For this reason, snorkel observation is the only feasible option for collecting physiological and behavioral data without directly impacting individuals. Collection for the ultimate purpose of propagating offspring should be conducted via careful seining, while limiting stress during the handling phases.

Sampling for this species should additionally be conducted in similar, well suited habitat both between its two current know locations, and in either direction to discover if unknown populations exist elsewhere. Uncovering hidden populations could hold the key to incorporating new genetics into the stagnant gene pool, and rebound the species to a healthy sustainable level. Realistically, lack of funds limits the amount of research and sampling that can be conducted in order to gather more information about this elusive and exceedingly rare Siluriform. Since only two locations have been discovered holding a very small population of these animals, it is essential that these areas be protected to the fullest extent.

Sources

- Gimenez Dixon, M. 1996. Noturus stanauli. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 4 August 2007.

- Dinkins, G.R. 1984. Aspects of the life history of the smoky madtom (Noturus baileyi) in Citico Creek. M.S. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN. 50pp.

- Dinkins, G.R., and P.W. Shute. 1993. Life histories of two federally listed madtom catfish, Noturus baileyi (smoky madtom) and N. flavipinnis (yellowfin madtom). Unpublished manuscript.

- Starnes, W. C., and L. B. Starnes. 1985. Ecology and life history of the mountain madtom, Noturus eleutherus (Pisces: Ictaluridae). Am. Midl. Nat. 114:331-341.

- Gutowski, M. J., and J. R. Stauffer, Jr. 1990. Feeding ecology of the margined madtom Noturus insignis (Richardson) (Teleos-tei: Ictaluridae). Abstract, 70th annual meeting ASIH (p. 95).

- Etnier, D. A., and R. E. Jenkins. 1980. Noturus stanauli, a new madtom catfish (Ictaluridae) from the Clinch and Duck Rivers, Tennessee. Bull. Alabama Mus. Nat. Hist. 5:17-22.

- Neves, R. J., and P. L. Angermeier. 1990. Habitat alteration and its effects on native fishes in the upper Tennessee River system, east-central U.S.A. J. Fish Biol. 37 (Supplement A), pp. 45–52.

- Starnes, W. C., and D. A. Etnier. 1986. Drainage evolution and fish biogeography of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers drainage realm. In: The Zoogeography of North American Freshwater Fishes (C. H. Hocutt, and E. O. Wiley, eds.), pp. 325–361. New York: John Wiley.

- Starnes, W. C., and D. A. Etnier. 1986. Drainage evolution and fish biogeography of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers drainage realm. In: The Zoogeography of North American Freshwater Fishes (C. H. Hocutt, and E. O. Wiley, eds.), pp. 325–361. New York: John Wiley.

- Sheldon, A. L. 1988. Conservation of stream fishes: patterns of diversity, rarity, and risk. Conservation Biology. 2:149-156.

- Tennessee Valley Authority. 1971. Stream length in the Tennessee River Basin. Tennessee Valley Authority, Knoxville, TN. 25 pp.

Categories:- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Fauna of the United States

- Noturus

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.