- Frecklebelly madtom

-

Frecklebelly madtom

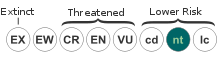

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Actinopterygii Order: Siluriformes Family: Ictaluridae Genus: Noturus Species: N. munitus Binomial name Noturus munitus

Suttkus & Taylor, 1965The frecklebelly madtom (Noturus munitus) is a species of fish in the Ictaluridae family. It is endemic to the United States. Madtoms are in the genus Noturus, which is a group of catfish prevalent to North America.

Contents

Description

The Noturus munitus (Frecklebelly madtom) is a robust, boldly patterned member of the monophyletic saddled madtom subgenus Rabida [1]. Historically the population thrived in large rivers in the Mobile Basin and Pearl River drainages in the southeastern United States [2]. However, it is currently limited to the Coastal Plain rivers [3]. The species lives exclusively in medium to large rivers free of sedimentation and over gravel shoals [3]. They spawn between June and August while producing 50 to 75 mature eggs in a single clutch size [3].

All madtoms species, including Noturus munitus have experienced much decline since the 1950’s due to channelization, gravel mining, dredging, and siltation. These activities reduce the ability for the species to properly breed and survive. An effective management plan for this species should concentrate on habitat protection and further biological research. A potential plan could include: monitoring species populations, preventing construction of dams, conducting biological research, and developing riparian buffer zones. Once riparian habitat and stream restoration are created and maintained, the reintroduction of Noturus munitus could be possible.

Geographic Distribution

Noturus munitus is a diminutive catfish with a disjunct distribution across the southeastern United States. It is historically known from the Pearl River drainage in MS and LA, the Upper Tombigbee River drainage in MS and AL, the Alabama River and Cahaba River drainages in Al. However, it has been extirpated from the main channel of Tombigbee and Alabama River, and is currently limited to the Coastal Plain rivers [3]. The species lives exclusively in medium to large rivers free of sedimentation and over gravel shoals [3]. N. munitus has declined rapidly since the mid-1950’s when river modification began. The loss of gravel substrates and increased levels of sedimentation due to poor agricultural practices have also implicated the species. It is now reliably found in high numbers in only a few locations and is considered threatened with extinction [2].

Ecology

The habitats of Noturus munitus and other Noturus species are very specific. They have to have moving, cool water, with no sedimentation. This is why human modification of rivers is such an important subject when it comes to conserving this species and others. Dams interrupt the water regimes, and sedimentation can cover eggs preventing them to hatch. Also, according to research it is typical that large-river specialists frequently cohabitate. In a study published in the Southeastern Naturalist several large-river specialists were frequently collected with N. munitus, including Macrhybopsis sp.cf. aestivalis (Speckled Chub), Macrhybopsis storeriana (Silver Chub), Notropis uranoscopus Suttkus (Skygazing Shiner), Crystallaria asprella (Crystal Darter), Percina lenticula (Freckled Darter), and Percina vigil (saddleback Darter) [4]

Since Noturus. munitus is an opportunistic insectivore, like most of these fish, competition for food may be present in the ecology of the species. A diet analysis published in the Southeastern Naturalist, showed Bactidae nymphs (31%), hydropsychidae larvae (20%), and Simuliidae larvae (20%) provided most of the food volume for N. munitus [4]. Consequently, in the long run, managing for N. munitus would also benefit other species as well. On the other hand, another reason for decline that should be assessed is predators. However, published articles on madtom predators were hard to find. Though, like all madtoms, they are known for their pectoral spines that contain saw-like teeth and a neurotoxin gland. These spines and toxins produce a painful sting when utilized, and indicate the presence of predators.

Life History

N. munitus reproduction is similar to those of other madtom species. They spawn between June and August while producing 50 to 75 mature eggs in a single clutch size [3]. They also prefer to make homes in cavities under rocks. They use these cavities for spawning. The male locates and guards a suitable site while the female deposits the eggs. The male then protects the eggs from predators and keeps them clean until they hatch. This is why sedimentation plays such a big role in the decline of the species. Sedimentation can cover the eggs and cause them to die. If successful it will reach reproductive maturity during the second summer of life [4], and will live 2-3 years [3].

Current Management

Of the 29 Noturus species, more than 50% are considered vulnerable, imperiled, or extinct, and many are likely in need of conservation action due to small ranges and increasing anthropogenic threats [5]. Much of this decline is due to human impacts such as: water impoundment, channelization, gravel mining, dredging, and siltation. These activities reduce the ability for the species to properly breed and survive. Its habitat specificity and lack of published research are also affecting further conservation actions. To reduce these human impacts the species needs to be considered for a federal threatened status. They are protected in MS and AL, however not legally protected in LA. The Alabama Forever Wild Land Trust has aimed to protecting habitat sites that would be utilized by N. munitus. [3] However, besides that there is no direct management for the species.

Conservation

Conservation recommendations include:

- First, to be done is to have the species federally listed as a threatened species [3], beyond the existing IUCN Red List near threatened species status, and to monitor the populations. The most effective way to monitor the species would be to use seines in specific sites and count the number of captured specimens. Historic population sites, and potential population sites should be surveyed. Anywhere with suitable gravel-riffle habitats would be considered potential sites. It would also be useful to sample each site for 30 minutes once a year.

- Secondly, the habitats need to be protected. Human modification needs to be eliminated, and the development of riparian buffer zones should be encouraged. Riparian areas filter out excessive sedimentation and maintain erosion. These buffer zones could also increase insect abundance and larvae. N.munitus’ trophic ecology appears to be typical of other small benthic fishes, and aquatic insect larvae comprise the bulk of the diet [6].

- Thirdly, further research of the species would be beneficial. Successful conservation of aquatic biodiversity in the future will depend on accurate knowledge of species habitat and life-history traits, the communities and ecosystems they occupy, recognition and description of evolutionary diversity within currently described species, and our ability as scientists to educate and involve more citizens in research and conservation efforts [7].

References

- Angermeier, P.L. 2007. <refname="ref1"> The role of fish biologists in helping society build ecological sustainability. Fisheries 32:9-20.</ref>

- Bennett, Micah G., Arrington, Albrey D., Kuhajda, Bernard R., and Shepard, Thomas E. 2005. [3]

- Bennet, Micah G., Kuhajda, Bernard R., and Howell, Heath J. 2008. [2]

- Bennet, Micah G., Kuhajda, Bernard R., and Khudamrongsawat, Jenjit. 2010. [4]

- Boschung.H.T., Jr., and R.L. Mayden. 2004. [8]

- Burr, B.M., and J.N. Stoeckel. 1999.[5]

- Hardman. M. 2004. [1]

- Miller, Gary L. 1984. [6]

- Miller, G.L. 1983. [9]

- Piller, KR, Bart, HL, and Tipton, JA. 2004. [10]

Notes

- ^ a b The phylogenetic relationships among Noturus catfishes (Siluriformes:Ictaluridae) as inferred from mitochondrial gene cytochrome b and nuclear recombination activating gene 2. Molecular phylogenetics and Evolution 30:395-408.

- ^ a b c Status of the Imperiled Frecklebelly Madtom, Noturus munitus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae): A Review of Data from Field Surveys, Museum Records, and the Literature. Southeastern Naturalist 7:459-474.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Threatened fishes of the world: Noturus munitus Suttkus & Taylor 1965 (Ictaluridae). Environmental Biology of Fishes 73:226.

- ^ a b c d Life-history Attributes of the Imperiled Frecklebelly Madtom, Noturus munitus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae), in the Cahaba River System, Alabama. Southeastern Naturalist 9(3): 507-520.

- ^ a b The natural history of madtoms (genus Noturus). North America’s diminutive catfishes. American Fisheries Society Symosium 24:51-101.

- ^ a b Trophic Ecology of the Frecklebelly Madtom Noturus munitus in the Tombigbee River, Mississippi. American Midland Naturalist. 111:8-15.

- ^ Threatened fishes of the world: Noturus munitus Suttkus & Taylor 1965 (Ictaluridae). Environmental Biology of Fishes 73:226.

- ^ Fishes of Alabama. Smithsonian Press. Washington. DC. 736pp.

- ^ Aspects of morphology and tropic ecology in a guild of stream fishes. Dissertation Abstracts International B Sciences and Engineering 43:2100.

- ^ Decline of the frecklebelly madtom in the Pearl River based on contemporary and historical surveys. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 133:1004-1013.

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Noturus

- Fauna of the Southeastern United States

- Fish of the United States

- Near threatened fauna of the United States

- Siluriformes stubs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.