- Camille Claudel

-

This article is about the artist. For the 1988 film, see Camille Claudel (film). For the musical, see Camille Claudel (musical).

Camille Claudel

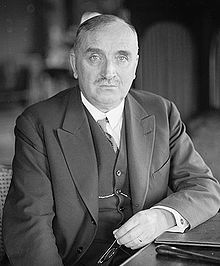

Camille Claudel in 1884 (aged 19)Born 8 December 1864

Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, France

Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, FranceDied 19 October 1943 (aged 78) Alma mater Académie Colarossi Influenced by Alfred Boucher, Jessie Lipscomb, Auguste Rodin Parents Louis Prosper

Louise Athanaïse Cécile CerveauxRelatives Paul Claudel Camille Claudel (8 December 1864 – 19 October 1943) was a French sculptor and graphic artist. She was the elder sister of the poet and diplomat Paul Claudel.

Contents

Early years

Camille Claudel was born in Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, in northern France, the second child of a family of farmers and gentry. Her father, Louis Prosper, dealt in mortgages and bank transactions. Her mother, the former Louise Athanaïse Cécile Cerveaux, came from a Champagne family of Catholic farmers and priests. The family moved to Villeneuve-sur-Fère while Camille was still a baby. Her younger brother Paul Claudel was born there in 1868. Subsequently they moved to Bar-le-Duc (1870), Nogent-sur-Seine (1876), and Wassy-sur-Blaise (1879), although they continued to spend summers in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, and the stark landscape of that region made a deep impression on the children. Camille moved with her mother, brother and younger sister to the Montparnasse area of Paris in 1881, her father having to remain behind, working to support them.

Creative period

Fascinated with stone and soil as a child, as a young woman she studied at the Académie Colarossi with sculptor Alfred Boucher. (At the time, the École des Beaux-Arts barred women from enrolling to study.) In 1882, Claudel rented a workshop with other young women, mostly English, including Jessie Lipscomb. Alfred Boucher became her mentor and provided inspiration and encouragement to the next generation of sculptors such as Laure Coutan and Claudel. The latter was depicted in "Camille Claudel lisant" by Boucher[1] and later she herself sculpted a bust of her mentor. Before moving to Florence and after having taught Claudel and others for over three years, Boucher asked Auguste Rodin to take over the instruction of his pupils. This is how Rodin and Claudel met and their tumultuous and passionate relationship started.

Around 1884, she started working in Rodin's workshop. Claudel became a source of inspiration, his model, his confidante and lover. She never lived with Rodin, who was reluctant to end his 20-year relationship with Rose Beuret. Knowledge of the affair agitated her family, especially her mother, who never completely agreed with Claudel's involvement in the arts[citation needed]. As a consequence, she left the family house. In 1892, after an unwanted abortion, Claudel ended the intimate aspect of her relationship with Rodin, although they saw each other regularly until 1898.

Beginning in 1903, she exhibited her works at the Salon des Artistes français or at the Salon d'Automne.

It would be a mistake to assume that Claudel's reputation has survived simply because of her once notorious association with Rodin. The novelist and art critic Octave Mirbeau described her as "A revolt against nature: a woman genius". Her early work is similar to Rodin's in spirit, but shows an imagination and lyricism quite her own, particularly in the famous Bronze Waltz (1893). The Mature Age (1900) whilst interpreted by her brother as a powerful allegory of her break with Rodin, with one figure The Implorer that was produced as an edition of its own, has also been interpreted in a less purely autobiographical mode as an even more powerful representation of change and purpose in the human condition.[2]

Her onyx and bronze small-scale Wave (1897) was a conscious break in style with her Rodin period, with a decorative quality quite different from the "heroic" feeling of her earlier work.

In the early years of the 20th Century, Claudel had patrons, dealers, and some commercial success.

Composer Claude Debussy has also been romantically linked to Claudel, but this was later proven as being false.[citation needed] Nevertheless, Debussy kept a copy of Claudel's La Valse on his mantel.[citation needed]

Illness

After 1905 Claudel appeared to be mentally ill. She destroyed many of her statues, disappeared for long periods of time, and exhibited signs of paranoia and was diagnosed as having schizophrenia.[3] She accused Rodin of stealing her ideas and of leading a conspiracy to kill her. After the wedding of her brother (who had supported her until then) in 1906 and his return to China, she lived secluded in her workshop.

Confinement

Her father, who approved of her career choice, tried to help her and supported her financially. When he died on 2 March 1913, Claudel was not informed of his death. On 10 March 1913 at the initiative of her brother, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital of Ville-Évrard in Neuilly-sur-Marne. The form read that she had been "voluntarily" committed, although her admission was signed by a doctor and her brother. There are records to show that while she did have mental outbursts, she was clear-headed while working on her art. Doctors tried to convince the family that she need not be in the institution, but still they kept her there[citation needed].

In 1914, to be safe from advancing German troops, the patients at Ville-Évrard were at first relocated to Enghien. On 7 September 1914 Camille was transferred with a number of other women, to the Montdevergues Asylum, at Montfavet, six kilometres from Avignon. Her certificate of admittance to Montdevergues was signed on 22 September 1914; it reported that she suffered "from a systematic persecution delirium mostly based upon false interpretations and imagination"[citation needed].

For a while, the press accused her family of committing a sculptor of genius. Her mother forbade her to receive mail from anyone other than her brother. The hospital staff regularly proposed to her family that Claudel be released, but her mother adamantly refused each time. On 1 June 1920, physician Dr. Brunet sent a letter advising her mother to try to reintegrate her daughter into the family environment. Nothing came of this.

Paul Claudel visited her every few years, though he referred to her in the past tense. In 1929 Jessie Lipscomb visited her and insisted "it was not true" that Claudel was insane. Rodin's friend, Mathias Morhardt, insisted that Paul was a "simpleton" who had "shut away" his sister of genius.[citation needed]

Camille Claudel died on 19 October 1943, after having lived 30 years in the asylum at Montfavet (known then as the Asile de Montdevergues, now the modern psychiatric hospital Centre Hospitalier de Montfavet), and without a visit from her mother or sister (her mother died on 20 June 1929). Her body was interred in the cemetery of Monfavet. No one from the family attended the ceremony (only a few members from the hospital staff). Later her remains were buried in a communal grave (the body was never claimed by her family)[citation needed].

Legacy

Though she destroyed much of her art work, about 90 statues, sketches and drawings survive.

Some authors argue that Henrik Ibsen based his last play, 1899's When We Dead Awaken, on Rodin's relationship with Claudel.[4][5][6][7]

In 1951, Paul Claudel organized an exhibition at the Musée Rodin, which continues to display her sculptures. A large exhibition of her works was organized in 1984. In 2005 a large art display featuring the works of Rodin and Claudel was exhibited in Quebec City, Canada and Detroit, Michigan, USA. In 2008, the Musée Rodin organized a retrospective exhibition including more than 80 of her works.

The publication of several biographies in the 1980s sparked a resurgence of interest in her work.

Camille Claudel (1988) was a dramatization of her life based largely on historical records. Directed by Bruno Nuytten, co-produced by Isabelle Adjani, starring herself as Claudel and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin, the film was nominated for two Academy Awards in 1989.

In 2003, plans were announced to turn the Claudel family home at Nogent-sur-Seine into a museum, which was negotiating to buy works from the Claudel family. These include 70 pieces by Camille Claudel, including a bust of Rodin.

Seattle playwright S.P. Miskowski's La Valse (2000) is a well-researched look at Claudel's life.[8]

Composer Wildhorn and lyricist Knighton's musical Camille Claudel was produced by Goodspeed Musicals at The Norma Terris Theatre in Chester, Connecticut in 2003.[9]

In 2005, Sotheby's sold a second edition La Valse (1905, Blot, number 21) for $932,500.[10] In a 2009 Paris auction, Claudel's Le Dieu Envolé (1894/1998, Valsuani, signed and numbered 6/8) has a high estimate of $180,000,[11] while a comparable Rodin sculpture, L'eternelle Idole (1889/1930, Rudier, signed) has a high estimate of $75,000.[12]

In 2007, the band The Poison Control Center released a song simply titled "Camille Claudel", based on Claudel's relationship with Rodin and his reluctance to part with Rose Beuret.

See also

- Category:Sculptures by Camille Claudel

Notes

- ^ Camille Claudel révélée, exporevue, magazine, art vivant et actualité at www.exporevue.com

- ^ The different scales, the different modes of plasticity, and gender-representation, of the three figures which make up this important group, enable a more universal thematic and metaphoric stylistics related to the ages of existence, childhood, maturity, and the perspective of the transcendent (v. Angela Ryan, "Camille Claudel: the Artist as Heroinic Rhetorician." Irish Women's Studies Review vol 8: Making a Difference: Women and the Creative Arts. (December 2002): 13-28).

- ^ http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0047-20852006000300012&script=sci_arttext

- ^ Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, J. Adolf (1994). Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel. Prestel. ISBN 3791313827, 9783791313825.

- ^ Bremel, Albert (1996). Contradictory characters: an interpretation of the modern theatre. Northwestern University Press. pp. 282–283. ISBN 0810114410, 9780810114418.

- ^ Binding, Paul (2006). With vine-leaves in his hair: the role of the artist in Ibsen's plays. Norvik Press. ISBN 1870041674, 9781870041676.

- ^ Templeton, Joan (2001). Ibsen's women. Cambridge University Press. p. 369. ISBN 0521001366, 9780521001366.

- ^ http://www.seattlepi.com/theater/valseq.shtml

- ^ [1] Playbill News

- ^ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id=159563476

- ^ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id=159557282

- ^ http://www.sothebys.com/app/live/lot/LotDetail.jsp?lot_id=159567009

Bibliography

- Ayral-Clause, Odile. Camille Claudel: A Life. New York: Abrams, 2002.

- Lenormand-Romain, Antoinette et al. Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter. New York: Gingko Press, 2005.

- Rivière, Anne & Bruno Gaudichon. Camille Claudel: Catalogue raisonné. Paris: Adam Biro, 2001.

External links

- Review of 2008 Claudel exhibition at Musee Rodin, Paris[dead link]

- Camille Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter at Detroit Institute of Arts 2005

- Claudel pages, including biography and timeline, at rodin-web.org

- Camille Claudel at artcyclopedia.com

- Camille Claudel: a Life of Struggle[dead link]

- Camille Claudel, Of Dreams and Nightmares

- Camille Claudel: a Life of Struggle

- Camille Claudel, Of Dreams and Nightmares !- This link is broken-

- An Eye on Art: L'Age Mûr

- Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks: Camille Claudel

- CBC interview for the 2005 exhibition in Quebec

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) Works People and places Camille Claudel · Hôtel Biron, Paris · Musée Rodin, Paris · Rodin Museum, Philadelphia · Rodin Gallery, SeoulCategories:- 1864 births

- 1943 deaths

- People from Aisne

- French artists' models

- French sculptors

- French women artists

- People with schizophrenia

- Women sculptors

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.