- United States Constabulary

-

United States Constabulary

United States Constabulary patchActive 1946-1952 Country United States of America Allegiance Regular Army Branch U.S. Army Role Constabulary Size Division equivalent Nickname Circle C Cowboys Motto Mobility, Vigilance, Justice Disbanded 1952 Commanders Notable

commandersErnest Harmon

Withers A. Burress

Louis Craig

Isaac D. White

Thomas L. HarroldThe United States Constabulary was a United States Army military Constabulary force. From 1946 to 1952, in the aftermath of World War II, it acted as an occupation and security force in the U.S. Occupation Zone of West Germany and Austria.

Contents

Reason

The concept of a police-type occupation of Germany arose from the consideration of plans for the most efficient employment of the relatively small forces available.

The speed of redeployment in the fall of 1945, and the certainty that the occupational troop basis would have to be reduced speedily, dictated the utmost economy in the use of manpower. The basic principle of the police-type occupation—that the lack of strength in the forces of occupation must be made up for by careful selection, rigid training, and high mobility—cannot be attributed to any single individual, or indeed to any single agency. Before any plans were worked out for the organization of the United States Constabulary, units of the United States Army assigned to occupational duties in Germany had experimented with the organization of parts of their forces into motorized patrols for guarding the borders and maintaining order in the large areas for which they were responsible. In September 1945, the G-2 Division of European Theater Headquarters put forward a plan, which was carried into effect towards the end of the years for the organization of a special security force known as the District Constabulary. In October 1945, the War Department asked European Theater Headquarters to consider the feasibility of organizing the major portion of the occupational forces into an efficient military police force on the model of state police or constabulary in the United States.

Ideas crystallized rapidly. At the end of October 1945, General Eisenhower, then Theater Commander, announced to the proper authorities that the population of the United States Zone of Germany would ultimately be controlled by a super-police force or constabulary. In early November, the strength of the proposed constabulary was announced as 38,000. Planning was well advanced by the end of 1945, when the European Theater Headquarters notified the War Department that the constabulary would be organized as an elite force, composed of the highest caliber personnel obtainable under the voluntary re-enlistment program, and that it would be equipped with an efficient communications network, sufficient vehicles and liaison airplanes to make it highly mobile, and the most modern weapons. During the paper stage, the organization was known by a series of names. "State Police" was discarded for "State Constabulary." Then it was thought that "State" would be confusing, as the main United States Zone of Germany had been divided, for purposes of civil administration, into three states, or Länder. Then the organization emerged from the planning stage, it as known as the "Zone Constabulary," but before it became operational it was named "United States Constabulary."

Command and staff

On 10 January 1946, Major General Ernest N. Harmon, wartime commander of the 1st and 2d Armored Divisions and the XXII Corps, was appointed Commanding General of the United States Constabulary.

At the direction of Lieutenant General Lucian K. Truscott, Commanding General, Third United States Army, a small group was detailed to assist General Harmon in carrying forward the planning for the new force. Its headquarters was established at Bad Tölz. Theater Headquarters had already announced the principle that the Constabulary would be organized along geographical lines to coincide as nearly as possible with the major divisions of the German civil administration, in order to facilitate liaison with the German police and United States Offices of Military Government. Thus, there would be one Constabulary Headquarters for the entire United States Zone, a brigade headquarters at each of the capitals of the three German Länder, and group, squadron, and troop headquarters established at points selected for ease in performing the mission. Theater Headquarters had also directed that the organization charts of the Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron would be used in planning the organization of the Constabulary.

The primary unit of the Constabulary, the troop, was organized on the pattern of the mechanized cavalry troop used in the war. In view of its tasks of road and border patrolling and its police-type jobs, the Constabulary needed a greater number of hand weapons and light vehicles, such as jeeps and armored cars. Each troop was divided for patrolling purposes into sections or teams, each of which was equipped with three jeeps and one armored car serving as a command vehicle and as support in case of emergency. A mobile reserve of one company equipped with light tanks was established in each Constabulary regiment. Horses were provided for patrolling in difficult terrain along the borders and motorcycles for the control of traffic on the super-highways (Autobahnen). Static border control posts were established at the crossing points.

Uniforms

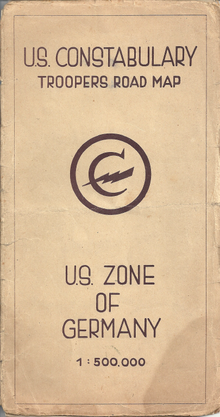

The uniform of the Constabulary trooper was designed both to make him easily recognizable and to distinguish him as a member of an elite force. The "Lightning Bolt" shoulder patch consisting of a circular yellow shoulder patch with the border of the patch and the letter "C" in the middle being in blue. A red lightning bolt appeared diagonally going down from right to left in the center of the "C". The yellow, blue, and red combined the colors of the cavalry, infantry, and artillery. Their motto was "Mobility, Vigilance, Justice." To make the troops more distinctive they were given US Cavalry bright golden yellow scarves, combat boots with a smooth outer surface designed to be spit shined, and helmet liners bearing the Constabulary insignia and yellow and blue stripes. One ex-member of the force remembered being called a "circle C cowboy" by soldiers from American regular army units.

Creation

To create a high morale in the Constabulary as quickly as possible, elements of the 1st and 4th Armored Divisions and certain cavalry groups were assigned to form the basis for the new organization. The units converted into Constabulary squadrons and regiments included armored infantry, field artillery, tank, tank destroyer, antiaircraft battalions, and mechanized cavalry squadrons. The Constabulary was also called the Circle C Cowboys because they had approximately 300 horses on duty in Berlin, the U.S. Zone of Germany, and Austria, with two veterinarians to treat them.

Organization

The VI Corps Headquarters became the Headquarters, United States Constabulary.

The 1st Armored Division, activated at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in June 1940 and one of the first American divisions to fight on the other side of the Atlantic, supplied many tank and infantry units.

The 4th Armored Division furnished the three brigade headquarters for the Constabulary.

These veteran units, seriously depleted by redeployment, now approached a task quite different from that of waging war, but one demanding initiative and high standards in training and discipline. Some of the combat units assigned to the Constabulary were carried temporarily as mere paper organizations, redeployment having taken all their officers and men. Other units had up to 75 percent of their allotted strength, but all the units taken together averaged only 25 percent of their authorized strength.

In February 1946, Constabulary Headquarters was established in Bamberg. During the period when tactical units, released from the Third and Seventh Armies, were being redesignated as Constabulary units, the main tasks were training and reorganization. Continuous training was prescribed for the trooper so that he might attain an acceptable standard of discipline and all around efficiency in the use of weapons, vehicles, and communications equipment.

Education and training

Early in the planning stage the need for a Constabulary School became evident.

The Constabulary trooper, it was seen, must know, not only the customary duties of a soldier, but also police methods, how to make arrests, and how to deal with a foreign population. A school was also needed to develop among the members of the Constabulary a spirit which would lift them towards the required high standards of personal appearance, soldierly discipline, and unquestioned personal integrity. The Constabulary School was established at Sonthofen, Germany, in a winter sports area at the foot of the Allgau Alps. This citadel had been formerly used as a Nazi school to train youthful candidates for positions of leadership in the Party. The curriculum for Constabulary officers and noncommissioned officers included instruction in the geography, history, and politics of Germany. The technical and specialist training for the trooper included the theory and practice of criminal investigation, police records, self-defense, and the apprehension of wanted persons. The trooper's indoctrination in the mission of the Constabulary gave him a knowledge of his responsibilities and the functions of the Constabulary. The Constabulary School had standards comparable to those of Army Service Schools in the United States. A graduate of Sonthofen was qualified, not only to perform his duties, but also to serve as an instructor in his unit. By the end of 1946, 5,700 officers and enlisted personnel had been graduated.

A Trooper's Handbook was written to cover the basic rules to be followed by him in the execution of his duties. To prepare this manual, the Constabulary obtained the services of Colonel J. H. Harwood, formerly State Police Commissioner of Rhode Island.

The training program, as originally planned, aimed at the progressive development of the Constabulary so as to attain a common standard of efficiency throughout the organization. 1 July 1946 was set as the date upon which the Constabulary would become operational and, in preparation for that day, the training program was divided into three phases. During the first phase, prior to 1 April, attention was concentrated on the training of cadre and on the establishment of regimental and squadron headquarters so that the Constabulary would be prepared to receive the approximately 20,000 men expected to fill the ranks. During this phase, the emphasis from the point of view of control by the main headquarters was shifted from the squadron to the regiment, since each of the latter directed three of the former. The second phase, between 1 April and 1 June, was a period of intensive training in the duties of both individuals and units. The final phase was planned as on-the-job training during June. The last phase, however, was not completed because of delay in receiving reinforcements.

The Constabulary became operational on 1 July 1946 as scheduled, despite the fact that its training program had not been completed. Changes in the redeployment rules caused the loss within a few weeks of 8,000 troopers, 25 percent of the total strength. During the first two months of operations 14,000 men, or 42.7 percent of the total strength, were lost through redeployment. The replacement and training task at that time were staggering. To make matters worse, there was a critical shortage in the Constabulary of junior officers during the late summer of 1946. This delayed the Constabulary in attaining the desired standards in discipline and operations, and was the cause of many changes in operational techniques.

Despite all of these difficulties, the Constabulary attained its goal of selecting high caliber personnel. The main reason for seeking troopers of high caliber and for giving them higher ratings than are available in other military organizations was the realization that the Constabulary was only as good as the individual trooper. Small groups of two or three troopers operated far from their headquarters and were empowered with unusual authority in matters of arrest, search, and seizure. In conducting their daily duties, they faced many temptations, such as those offered by persons willing to pay almost any price for immunity after crossing the border, or for illegal concessions in the black market. Maintaining high standards in the Constabulary was all the more difficult because most of the combat veterans had gone home and had been replaced by men in the age group of 18 to 22 years.

Mission

The mission of the United States Constabulary was to maintain general military and civil security, to assist in the accomplishment of the objectives of the United States government in Germany, and to control the borders of the United States Zone.

The Constabulary set up a system of patrols throughout the entire area and along the borders. The territory to be patrolled had an area of over 40,000 square miles (100,000 km²) and included nearly 1,400 miles of international and interzonal boundaries, extending from Austria in the South to the British Zone in the North, and from Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Zone in the East to the Rhine River and the French Zone in the West. Approximately the area of Pennsylvania in size, the United States Zone of Occupation in Germany had similar contours, with flat lands, hills, mountains, and forests, crisscrossed by many rivers and streams. More than sixteen million German people lived in this area, and it included many cities of considerable size. The entire Zone was covered by a network of roads, while here and there were the Autobahnen—the four-lane express highways.

Operations

At first the Constabulary tried to patrol everywhere in the Zone.

Troopers traveled on country roads, through small villages, over narrow and rough mountainous roads. They moved up and down the streets of large cities like Munich and Stuttgart, and of the smaller ones like Fritzlar, Weiden, Hof, and Passau—names which have become as familiar to the Constabulary trooper as Pittsburgh, Akron, Richmond, Clay Center, and Abilene. Wherever patrols operated, they were in constant communication by radio or telephone with their platoon or troop headquarters, which were in turn linked in a chain of communications reaching up to Constabulary Headquarters. The telephone lines used by the Constabulary were, for the most part, those of the German system, although some military lines and equipment were also available. In addition to radio and telephone, the Constabulary was hooked up in a teletype system, which was the most comprehensive and effective communications network operated by the United States Army in Europe.

In the performance of their mission, Constabulary patrols visited periodically the German mayors (Buergermeister), German police stations, United States investigating agencies, and other military units in their areas. They were always prepared to assist any one or all of these. Like the State police units in the United States, Constabulary patrols worked closely with the municipal, rural, and border police, even though the German police were part of the administration of an occupied country. The Constabulary troopers became acquainted with the local policemen, received reports from them of what occurred since the last visit, and worked out with them methods of trapping criminals and of forestalling possible disturbances.

As they roamed their beat in their yellow and blue striped jeep, each pair of Constabulary troopers was usually accompanied by a German policeman who rode in the back seat. The German policeman knew some English and the troopers were trained at the Constabulary school to understand a number of German phrases useful in police work. If the patrol investigated a disturbance in a German home, the troopers stood by while the German officer made the arrest. If they apprehended suspected displaced persons outside their camp, the troopers again stood by while the German policeman handles the situation. If the offender was an American or Allied soldier or civilian, the troopers made the arrest. This procedure built up the prestige of the new German police in the eyes of their own people.

Border control was an important element in the security of the United States Zone. On 1 July 1946, the Constabulary replaced the troopers of the 1st, 3d, and 9th Infantry Divisions at the many static control posts along the borders. At these border posts, often in isolated locations, Allied soldiers met and exchanged greetings across the red and white barricades as they performed their duties of customs inspection, passport control, and law enforcement. During the second half of 1946, 120 border posts employing 2,800 Constabulary troopers turned back from the border over 26,000 undocumented transients. An additional 22,000 illegal crossers were apprehended by patrols within the ten-mile (16 km) border zone and turned over to military government. As the patrols of the Constabulary increased, illegal crossings showed a downward trend because travelers became aware of the regulations and the effectiveness of the Constabulary in their enforcement.

Modernization

As a result of continuous study of crime statistics, emphasizing the location and time of commission, the patrolling of the interior areas of the American Zone was modified so as to provide for more frequent visits to disorderly areas than to the relatively quiet localities.

The potential sources of trouble were judged to be, not in rural areas where peasants gazed in wonder at Constabulary patrols, but in areas where large urban populations scrambled among ruins for food and for jury-built shelter. Here the patrols, passing every two hours, found that they were missing the real disturbances. Night reports of holidays and weekends told of assaults, robbery, and other serious crimes being perpetrated, but too often the Constabulary was not on the spot to act. Again, operating procedures were changed to provide for concentration on the high-incident areas at critical times. In large cities, tanks, armored cars, and jeeps of the Constabulary paraded in the streets in considerable numbers to show the Germans that the Americans meant business, and were properly trained and equipped to meet emergencies.

Troopers' lives

As the Constabulary trooper became accustomed to his duties, he gained more confidence and self-assurance. He possessed a thorough knowledge of police functions; he learned not to abuse his authority. No situation seemed insoluble. Consequently, two or three men could answer a call for assistance where formerly a section or more had gone out.

In the Kaserne the trooper had the recreational facilities and comforts which constituted his home life in Germany—Service Men's Clubs with their snack bars and entertainments, motion pictures, American Red Cross facilities, and trans-Atlantic telephone service. The trooper whose family lived in a military community found living and recreation within his means. All members of the Constabulary and their families had the possibility of interesting and enjoyable travel in Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Italy.

During the first six months of its activities the Constabulary made 168,000 patrols in jeeps, tanks, and armored cars, and on horseback and on foot. Its troopers traveled on these patrols more than five million miles, mostly in jeeps. The mileage covered by the vehicles of the United States Constabulary was equivalent to nine vehicles circling the earth every twenty-four hours. The mileage covered by foot patrols was equivalent to circling the globe once each week. The liaison airplanes of the Constabulary flew more than 14,000 hours on 11,000 missions during the first six months' period.

In 1946, the Constabulary made many swoop raids, known officially as "check and search operations," against displaced persons' and refugees' camps and the German population. No raids were made unless requested by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, military commanders, military government, or investigative agencies which had reason to suspect black-market or subversive activities. The trooper operating in the municipalities was a deterrent to the individuals and groups who are the mainstay of the black market. In six months, 2,681 black-market transactions and 173 subversive acts were uncovered in Constabulary operations.

The Constabulary assisted military government in the reorganization and development of the German police force. The Constabulary realized that its task would be greatly simplified with an increase in the strength and efficiency of the German police, a rise in the self confidence of German police officers, and a gain in their prestige in the eyes of the civilian population. The ties between the two law-enforcement agencies steadily became stronger. The Constabulary left the less important matters in the hands of the German police and concentrated more and more on the apprehension of major criminals and black marketeers. Eventually, the United States Constabulary played mainly the role of adviser and supporter, ready to assist the German police on call.

Equipment

From the beginning, the Constabulary set high standards for itself.

The troopers were selected from the best soldiers available, and it was desired that all of them be volunteers. They were to be trained as both soldiers and policemen. They were to operate in an efficient, alert manner calculated to inspire confidence and respect in all persons they met, whether Germans, Allies, or Americans. Next to its need for well-qualified men, the Constabulary depended most, for success in its mission, upon its system of communications and upon vehicles suited to the needs of the job and to the condition of the German roads. Better radio equipment was being furnished at the end of 1946, though it was not yet of the standard of that used by State Police and Highway Patrol forces at home. The German telephone system, hampered by a lack of spare parts, was not in good condition. The jeep, while excellent for combat, did not prove to be the best vehicle for Constabulary patrol work. There were far too many accidents and some of them were undoubtedly due to defects in the design of the jeep with reference to the road conditions encountered. The jeep's best points were that it had the power and the sturdiness to travel German roads, then in a bad state of repair. If the roads were better maintained, the sedan would be a more satisfactory patrol vehicle.

To maintain its mobility, the Constabulary waged a constant struggle to overcome deficiencies in its transportation facilities. The vehicles originally issued to the Constabulary, numbering approximately 10,000, were taken from the large concentrations of combat motor vehicles left behind by units returning to the United States for demobilization. Many of these vehicles were already worn out in the campaign and many others had deteriorated in disuse. The original condition of the vehicles placed a severe test upon the Constabulary which, at the time it was inaugurated, had no service elements.

Strength

The US Constabulary consisted of up to 38,000 men organized into:

- Headquarters, United States Constabulary,

- Three Brigades,

- 1st, 2nd and 3rd

- 10 Regiments,

- 1st through 3rd and 5th through 9th, assigned to the brigades.

- The 4th Regiment, an independent unit with:

- Two squadrons in Austria and

- One squadron in West Berlin.

Controlling:

-

- Thirty Squadrons.

- Each battalion-size squadron had five (at first) and then later on only four company-size troops.

- Thirty Squadrons.

Disbanding

The Constabulary was disbanded in 1952, after Germany had developed its own federal police forces. Many of the troopers came home and joined local and state police forces.

As the perception of the threat to border security changed from one of criminal activity to a potential invasion by the Soviet Army, the border operations mission along the Soviet zones in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria was taken over by armored cavalry units of the U.S. Army.[1]

A small monument to the U.S. Constabulary was erected in 2008 on Patch Barracks in Germany.[2]

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.The original version of this article was copied from United States Army's Constabulary History.

Further reading

Robert Perito, Where is the Lone Ranger When We Need Him?, outlines a proposal for integrating military and civilian personnel to form a “U.S. force for stability” that would become part of a U.S. intervention force.

External links

- The U.S. Constabulary in Post-War Germany (1946-52)(USACMH)

- United States Constabulary Association homepage

- US Army Germany official USC page

- US Army Command and General Staff College PDF article

- US Army Command and General Staff College PDF article on the establishment on use of a modern USC

- Chapter 3 Constabularies Riding Through History of Elusive Peace: U.S. Constabulary Capabilities in the Post-Cold War World by Tammy S. Schultz

Categories:- Military history of Germany

- Military police agencies of the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.