- PDCA

-

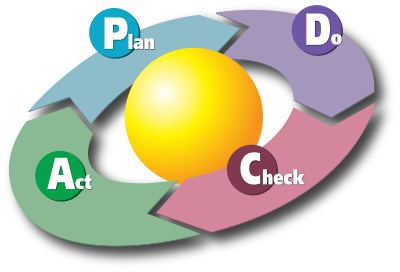

PDCA (plan–do–check–act) is an iterative four-step management method used in business for the control and continuous improvement of processes and products. It is also known as the Deming circle/cycle/wheel, Shewhart cycle, control circle/cycle, or plan–do–study–act (PDSA).

Contents

Meaning

The steps in each successive PDCA cycle are[2][3] :

- PLAN

- Establish the objectives and processes necessary to deliver results in accordance with the expected output (the target or goals). By establishing output expectations, the completeness and accuracy of the specification is also a part of the targeted improvement. When possible start on a small scale to test possible effects.

- DO

- Implement the plan, execute the process, make the product. Collect data for charting and analysis in the following "CHECK" and "ACT" steps.

- CHECK

- Study the actual results (measured and collected in "DO" above) and compare against the expected results (targets or goals from the "PLAN") to ascertain any differences. Charting data can make this much easier to see trends over several PDCA cycles and in order to convert the collected data into information. Information is what you need for the next step "ACT".

- ACT

- Request corrective actions on significant differences between actual and planned results. Analyze the differences to determine their root causes. Determine where to apply changes that will include improvement of the process or product. When a pass through these four steps does not result in the need to improve, the scope to which PDCA is applied may be refined to plan and improve with more detail in the next iteration of the cycle.

About

PDCA was made popular by Dr. W. Edwards Deming, who is considered by many to be the father of modern quality control; however he always referred to it as the "Shewhart cycle". Later in Deming's career, he modified PDCA to "Plan, Do, Study, Act" (PDSA) because he felt that “check” emphasized inspection over analysis.[4]

The concept of PDCA is based on the scientific method, as developed from the work of Francis Bacon (Novum Organum, 1620). The scientific method can be written as "hypothesis"–"experiment"–"evaluation" or plan, do and check. Shewhart described manufacture under "control"—under statistical control—as a three step process of specification, production, and inspection.[5] He also specifically related this to the scientific method of hypothesis, experiment, and evaluation. Shewhart says that the statistician "must help to change the demand [for goods] by showing [...] how to close up the tolerance range and to improve the quality of goods".[6] Clearly, Shewhart intended the analyst to take action based on the conclusions of the evaluation. According to Deming, during his lectures in Japan in the early 1950s, the Japanese participants shortened the steps to the now traditional plan, do, check, act.[7] Deming preferred plan, do, study, act because "study" has connotations in English closer to Shewhart's intent than "check".[2]

A fundamental principle of the scientific method and PDCA is iteration—once a hypothesis is confirmed (or negated), executing the cycle again will extend the knowledge further. Repeating the PDCA cycle can bring us closer to the goal, usually a perfect operation and output.[2]

In Six Sigma programs, the PDCA cycle is called "define, measure, analyze, improve, control" (DMAIC). The iterative nature of the cycle must be explicitly added to the DMAIC procedure.[citation needed]

PDCA should be[why?] repeatedly implemented in spirals of increasing knowledge of the system that converge on the ultimate goal, each cycle closer than the previous. One can envision an open coil spring, with each loop being one cycle of the scientific method - PDSA, and each complete cycle indicating an increase in our knowledge of the system under study. This approach is based on the belief that our knowledge and skills are limited, but improving. Especially at the start of a project, key information may not be known; the PDCA—scientific method—provides feedback to justify our guesses (hypotheses) and increase our knowledge. Rather than enter "analysis paralysis" to get it perfect the first time, it is better to be approximately right than exactly wrong. With the improved knowledge, we may choose to refine or alter the goal (ideal state). Certainly, the PDCA approach can bring us closer to whatever goal we choose.[8]

Rate of change, that is, rate of improvement, is a key competitive factor in today's world. PDCA allows for major 'jumps' in performance ('breakthroughs' often desired in a Western approach), as well as Kaizen (frequent small improvements). In the United States a PDCA approach is usually associated with a sizable project involving numerous people's time, and thus managers want to see large 'breakthrough' improvements to justify the effort expended. However, the scientific method and PDCA apply to all sorts of projects and improvement activities.[9]

See also

- AIDA process

- Business process improvement

- COBIT

- Creative Problem Solving Process

- DMAIC

- Lesson study

- OODA loop

- Performance management

- Quality management

- Quality storyboard

- Robert S. Kaplan (closed loop management system)

- Total Security Management

Further reading

- Shewhart, Walter Andrew (1980). Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Product/50th Anniversary Commemorative Issue. American Society for Quality. ISBN 0-87389-076-0.

- The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance, 2nd Edition by Gerald J. Langley, Ronald Moen, Kevin M. Nolan, Thomas W. Nolan, Clifford L. Norman, Lloyd P. Provost Published by Jossey-Bass ISBN 978-0-470-19241-2

- Shewhart, Walter Andrew (1939). Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-65232-7.

- Deming, W. Edwards (1986). Out of the Crisis. MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study. ISBN 0-911379-01-0.

References

- ^ "Taking the First Step with PDCA". 2 February 2009. http://blog.bulsuk.com/2009/02/taking-first-step-with-pdca.html. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Moen and Norman. "Evolution of the PDCA Cycle". http://pkpinc.com/files/NA01MoenNormanFullpaper.pdf. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ ISO 9001 Quality Management Systems - Requirements. ISO. 2008. pp. vi.

- ^ Anderson, Chris. How Are PDCA Cycles Used, Bizmanualz, June 7, 2011.

- ^ Shewhart (1939), p. 45

- ^ Shewhart (1939), p. 48

- ^ Deming, p. 88

- ^ Rother, Mike (2009), Toyota Kata, McGraw-Hill, p. 160

- ^ Rother, Mike (2009), Toyota Kata, McGraw-Hill, p. 76

External Links

Categories:- Management

- Quality

- American inventions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.