- Valeria Messalina

-

Valeria Messalina

Empress consort of the Roman Empire Tenure 24 January AD 41 – AD 48

(7 years)Spouse Claudius Issue Claudia Octavia, Empress of Rome

Tiberius Claudius Caesar BritannicusHouse Julio-Claudian (by marriage)

gens Valeria (by birth)Father Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus Mother Domitia Lepida the Younger Born 25 January AD 17 or AD 20

Rome, Roman EmpireDied AD 48 (aged 31 or 28)

Gardens of Lucullus, Rome, Roman EmpireValeria Messalina,[1] sometimes spelled Messallina, (c. 17/20 – 48) was a Roman empress as the third wife of the Emperor Claudius. She was also a paternal cousin of the Emperor Nero, second cousin of the Emperor Caligula, and great-grandniece of the Emperor Augustus. A powerful and influential woman with a reputation for promiscuity, she conspired against her husband and was executed when the plot was discovered. Asteroid 545 Messalina is named after her.

Contents

Family and early life

Messalina was the first daughter and second child of Domitia Lepida the Younger and her first cousin Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus.[2][3] Messalina's father was the son of Marcus Valerius Messala Barbatus Appianus,[4] a Claudius Pulcher by birth (son of Appius Claudius Pulcher, consul 38 BC) adopted by Marcus Valerius Messala, cos. suff. 32 BC.[5][6] His mother was Claudia Marcella Minor. Messalina's elder brother, Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, served as consul in AD 58. Her mother was the youngest child of the consul Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus and Antonia Major. Domitia Lepida had two siblings: Domitia Lepida the Elder, and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Domitius was the first husband of the future Augusta Agrippina the Younger and the biological father of the Princeps Nero, making Nero Messalina's first cousin despite a seventeen year age difference. Messalina's grandmothers Claudia Marcella and Antonia Major were half sisters. Claudia Marcella, Messalina's paternal grandmother, was the daughter of Augustus' sister Octavia the Younger by her marriage to Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor. Antonia Major, Messalina's maternal grandmother, was the elder daughter of Octavia by her marriage to Mark Antony, and was Claudius's maternal aunt.

Born no later than 12 BC and on the basis of his family distinction, Messalina's father could have expected a consulship by 23. Since he didn't become consul, he most likely died before that date.[7] Her mother then married the consul Faustus Cornelius Sulla Lucullus III, great-grandson of the Roman Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Faustus and Lepida had a son around AD 22, Faustus Cornelius Sulla Felix, Messalina's half brother. Faustus was consul in AD 52. Messalina was probably born and raised in Rome. Little is known about her life prior to her marriage to Claudius in AD 38.

Marriage to Claudius

Either in 37 or 38, Messalina married her second cousin Claudius, who was about 48 years old. During the reign of another second cousin of hers, the unstable Emperor Caligula (reigned 37-41), Messalina was very wealthy, an influential figure and a regular at Caligula's court. Claudius was Caligula's paternal uncle and was becoming influential and popular. Claudius probably married her to strengthen ties within the imperial family. Upon marrying Claudius, Messalina became a stepmother to Claudia Antonia, Claudius's daughter through his second marriage to Aelia Paetina.

Messalina bore Claudius two children: a daughter Claudia Octavia (born 39 or 40), who was a future empress, stepsister and first wife to the emperor Nero; and a son, Britannicus (born 41). On January 24, AD 41, Caligula and his family were murdered by a conspiracy led by Cassius Chaerea, and later that day, the Praetorian Guard proclaimed Claudius the new emperor and Messalina the new empress.

Roman Empress

Messalina became the most powerful woman in the Roman Empire. Claudius bestowed various honors on her: her birthday was officially celebrated, statues of her were erected in public places and she was given the privilege of occupying the front seats at the theatre along with the Vestal Virgins. The Roman Senate wanted Messalina to have the title of "Augusta"; however, Claudius refused.

In 43, Claudius held a triumphant military parade to celebrate the successful campaign in Britain. Messalina followed his chariot in a covered carriage and behind her marched the generals.

Through her status, she became very influential, however in character was very insecure. Claudius, as an older man, could have died at any moment and Britannicus would have become the new emperor. To improve her own security and ensure the future of her children, Messalina sought to eliminate anyone who was a potential threat to her and her children.

Among those who were loyal to Messalina was consul Lucius Vitellius the Elder. He begged her as a tremendous privilege for him to remove Messalina's shoes.

Due to Claudius' devotion to her, Messalina was able to manipulate him into ordering the exile or execution of various people: the Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger; Claudius’ nieces Julia Livilla and Julia; Marcus Vinicius (husband of Julia Livilla); consul Gaius Asinius Pollio II (see Vipsania Agrippina), the elder Poppaea Sabina (mother of Empress Poppaea Sabina, second wife of Nero), consul Decimus Valerius Asiaticus and Polybius. Claudius had the reputation of being easily controlled by his wives and freedmen.

A well known example of Messalina trying to eliminate her rivals was when Agrippina the Younger returned from exile after January 14. Agrippina was a niece to Claudius, a daughter of Claudius’ late brother Germanicus. Messalina realised that Agrippina's son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (the future Nero) was a threat to her son's position and sent assassins to strangle Nero during his siesta. When they approached his couch, they saw what appeared to be a snake near his pillow and fled in terror. The apparent snake was actually a sloughed-off snake skin.

Reputation

The ancient Roman sources, particularly Tacitus and Suetonius, portray Messalina as extremely lustful, but also insulting, disgraceful, cruel, and avaricious; they claimed her negative qualities were a result of her inbreeding. The oft-repeated tale of Messalina's all-night sex competition with a prostitute comes from Book X of Pliny the Elder's Natural History. Pliny does not name the prostitute; however, the Restoration playwright Nathaniel Richards calls her Scylla in The Tragedy of Messalina, Empress of Rome, published in 1640, and Robert Graves in his novel Claudius the God also identified the prostitute as Scylla. According to Pliny, the competition lasted for 24 hours and Messalina won with a score of 25 partners.

Roman sources claim that Messalina used sex to enforce her power and control politicians, that she had a brothel under an assumed name and organised orgies for upper class women, and that she sold her influence to Roman nobles or foreign notables.

Juvenal is also highly critical of her in his Satire VI (first translation by Peter Green and second translation from wikisource):

- Then consider the God's rivals, hear what Claudius

- had to put up with. The minute she heard him snoring

- his wife - that whore-empress - who dared to prefer the mattress

- of a stews to her couch in the Palace, called for her hooded

- night-cloak and hastened forth, with a single attendant.

- Then, her black hair hidden under an ash-blonde wig,

- she'd make straight for her brothel, with its stale, warm coverlets,

- and her empty reserved cell. Here, naked, with gilded

- nipples, she plied her trade, under the name of 'The Wolf-Girl',

- parading the belly that once housed a prince of the blood.

- She would greet each client sweetly, demand cash payment,

- and absorb all their battering - without ever getting up.

- Too soon the brothel-keeper dismissed his girls:

- she stayed right till the end, always last to go,

- then trailed away sadly, still, with burning, rigid vulva,

- exhausted by men, yet a long way from satisfied,

- cheeks grimed with lamp-smoke, filthy, carrying home

- to her Imperial couch the stink of the whorehouse.

- Then look at those who rival the Gods, and hear what Claudius

- endured. As soon as his wife perceived that her husband was asleep,

- this august harlot was shameless enough to prefer a common mat

- to the imperial couch. Assuming night-cowl, and attended by a single maid,

- she issued forth; then, having concealed her raven locks under a light-coloured peruque,

- she took her place in a brothel reeking with long-used coverlets.

- Entering an empty cell reserved for herself, she there took her stand, under the feigned name of Lycisca,

- her nipples bare and gilded, and exposed to view the womb that bore thee, O nobly-born Britannicus!

- Here she graciously received all comers, asking from each his fee;

- and when at length the keeper dismissed his girls,

- she remained to the very last before closing her cell,

- and with passion still raging hot within her went sorrowfully away.

- Then exhausted by men but unsatisfied,

- with soiled cheeks, and begrimed with the smoke of lamps,

- she took back to the imperial pillow all the odours of the stews.

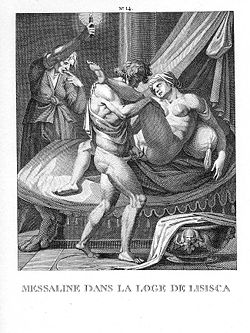

According to the Satire VI by Juvenal, Messalina worked in a brothel under the assumed name Lycisca, or 'The Wolf-Girl'. Etching by Agostino Carracci, late 16th century.

According to the Satire VI by Juvenal, Messalina worked in a brothel under the assumed name Lycisca, or 'The Wolf-Girl'. Etching by Agostino Carracci, late 16th century.

Downfall, death and aftermath

Troy Pageant

During the Secular Games in 47, at the performance of the Troy Pageant, Messalina attended the event with her son, Britannicus. Also present was Agrippina the Younger with her son, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (Nero). Agrippina and Nero received a greater acclamation from the audience than Messalina and Britannicus did. Many people began to show pity and sympathy for Agrippina, due to unfortunate circumstances that occurred in her life. This is probably a first sign of Messalina's declining popularity.

Affair with Gaius Silius

Later that year, Messalina became interested in the attractive Roman Senator Gaius Silius, who was married to the aristocratic woman Junia Silana (sister of Caligula's first wife Junia Claudilla). Messalina and Silius became lovers and Messalina forced Silius to divorce his wife.

Silius realised the danger in which he had put himself. Messalina and Silius plotted to kill the weak emperor and Messalina would make him the new emperor. Silius was childless and wanted to adopt Britannicus.

Plot discovery

While Claudius was in Ostia inspecting harbor construction, his freedman Tiberius Claudius Narcissus advised him of Messalina's and Silius’ plot to kill him. Messalina travelled to Ostia with her children hoping to speak to Claudius; however the emperor had left Ostia before she was able to do so. Narcissus had delayed Messalina, preventing her from seeing Claudius.

Execution

Claudius ordered the deaths of Messalina and Silius in 48. In Messalina's final hours, she was in the Gardens of Lucullus. Messalina and her mother Domitia Lepida were preparing a petition for Claudius. At the height of Messalina's influence and prosperity, Domitia Lepida and Messalina had argued and became estranged. Apparently overcome by pity, Lepida stayed with her daughter. Lepida's last words to her were ‘Your life is finished. All that remains is to make a decent end’. Messalina was reputedly weeping and moaning.[citation needed]

An officer and a former slave arrived together to witness Messalina's death. The former slave verbally insulted her while the officer stood by in silence. Messalina was offered the choice of killing herself, but was too afraid to do so, so the officer decapitated Messalina. Her dead body was left with her mother. At the time of Messalina's death, Claudius was attending a dinner. When Messalina's death was announced to him, Claudius showed no emotion, but asked for more wine.

Aftermath

In the days after her death, Claudius gave no sign of hatred, anger, distress, satisfaction, or any other passion. The only ones who mourned for Messalina were her children. The Roman Senate ordered Messalina's name removed from all public or private places and all statues of her removed.

On New Year's Day in 49, Claudius married, as his fourth wife, his niece Agrippina the Younger, who went on to remove from the imperial court anyone she considered loyal to the memory of Messalina. Agrippina's son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was adopted by Claudius as his son and heir. He became known as Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus and succeeded Claudius as emperor instead of Messalina's son Britannicus.

Fates of Messalina's children

- In AD 55, Britannicus was secretly poisoned on Nero's orders.

- Nero married Messalina's daughter Claudia Octavia in AD 53. Claudia Octavia was killed in AD 62 so that Nero could marry the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina. Poppaea's mother, who had died in AD 47, had been one of the victims of Messalina's intrigues.

Messalina's name is now often used as a synonym for sexual promiscuity, as well as manipulativeness and treachery.

Ancestry

Ancestors of Valeria Messalina 8. Appius Claudius Pulcher 4. Marcus Valerius Messala Barbatus Appianus 2. Marcus Valerius Messalla Barbatus 20. Marcus Claudius Marcellus 10. Gaius Claudius Marcellus Minor 21. Junia 5. Claudia Marcella Minor 22. (=30.)Gaius Octavius 11. (=15.)Octavia Minor 23. (=31.)Atia Balba Caesonia 1. Valeria Messalina 24. Lucius Domitius Ahnenobarbus 12. Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus 25. Porcia Catones 6. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus 13. Aemilia Lepida 3. Domitia Lepida the Younger 28. Marcus Antonius Creticus 14. Mark Antony 29. Julia 7. Antonia Major 30. (=22.)Gaius Octavius 15. (=11.)Octavia Minor 31. (=23.)Atia Balba Caesonia In fiction

Carlo Pallavicino's Venetian opera Messalina of 1680 deals with Valeria Messalina.

Messalina was featured prominently in Robert Graves' novels I, Claudius, and Claudius the God. In keeping with the historical views at the time the novels were written (1934–35), Messalina is portrayed as a young teenager at the time of her marriage. She is also credited with all the actions mentioned in the ancient sources. This character was played by Sheila White in the 1976 BBC television adaptation of the two books, and was played by Merle Oberon in Josef von Sternberg's 1937 uncompleted film of I, Claudius.

Besides the adaptation of Graves' work, the character of Messalina has been portrayed many times elsewhere in movies and television films or miniseries. Here are some of the other actresses who have played Messalina:

- Maria Caserini in the 1910 Italian silent film Messalina, directed by Enrico Guazzoni.

- Rina De Liguoro in the 1922 Italian silent film Messalina, directed by Enrico Guazzoni.

- María Félix in the 1951 Italian film Messalina, directed by Carmine Gallone.

- Susan Hayward in the 1954 Biblical epic Demetrius and the Gladiators, a completely fictionalized interpretation in which Messalina reforms and becomes a Christian.

- Belinda Lee in the 1960 film Messalina, Venere imperatrice.

- Sheila White in the 1976 BBC serial "I,Claudius".

- Anneka Di Lorenzo in the 1979 film Caligula, and the 1977 comedy Messalina, Messalina!, which used many of the same set pieces as the earlier-filmed, but later released Caligula[8].

- Jennifer O'Neill in the 1985 TV series A.D._(miniseries).

- Kelly Trump in the 1996 adult film Messalina, directed by Joe D'Amato.

- Sonia Aquino in the 2004 TV movie Imperium: Nero.

The French writer Alfred Jarry based his novel Messalina (or The Garden of Priapus in Louis Colman's English translation) on the myths surrounding the subject. She is referred to in his book Le Surmâle (in English the Supermale); these two books are offered as diametrically opposed entities in his 'pataphysical œuvre. The Messalinas of these books are highly fictionalized and subject to Jarry's fanciful and extravagant imagination.

In Robert Jordan's The Wheel of Time, the Forsaken Mesaana is named after Messalina. In Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, Messalina is a guest at Satan's ball. In Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, Mr. Rochester refers to his first wife as his Indian Messalina. In Leopold von Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs, the protagonist's aunt, who 'first aroused [his] desire for women' is referred to as a Messalina. Mario Puzo's The Last Don revolves around a film called "Messalina" based on the notorious all night exploits of the empress. Chuck Palahniuk's novel Snuff makes numerous references to Messalina's sexual exploits (in particular, the story of her competition with Scylla) as a sort of precedent for the feats attempted by the novel's central character. Messalina is the name given to a Native American orphan by a Presbyterian family before she is taken in by Jacob Vaark in Toni Morrison's 2008 novel A Mercy. She goes by the nickname Lina. In Gabriel García Márquez's Love in the Time of Cholera, a dog with many pups is named after the Empress. Messalina is also mentioned in Paulo Coelho's book "Eleven Minutes."

After being seduced, Jubal Harshaw refers to an accomplice as "You baby Messalina" in Robert Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land.

Messalina is also briefly mentioned in Oscar Wilde's novel The Picture of Dorian Gray in Chapter 6 as Lord Henry retorts to Basil's disapproval of Dorian's engagement: "If he wedded Messalina he would be none the less interesting".

In C.S. Lewis's essay Screwtape Proposes a Toast, the lead character, a devil giving a speech at the Tempter's College in Hell, makes reference to the dinner fare of 'Casserole of Adulterers': "To I who have tasted Messalina and Casanova they were nauseating."

Sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LX. 14-18, 27-31

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XX. 8; The Wars of the Jews II. 12

- Juvenal, Satires 6, 10, 14

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 10

- Plutarch, Lives

- Seneca the Younger, Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii; Octavia, 257-261

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Claudius 17, 26, 27, 29, 36, 37, 39; Nero 6; Vitellius 2

- Tacitus, Annals, XI. 1, 2, 12, 26-38

- Sextus Aurelius Victor, epitome of Book of Caesars, 4

References

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1996). Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Roman Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Klebs, E.; H. Dessau, P. Von Rohden (ed.) (1897-1898). Prosopographia Imperii Romani. Berlin.

- Levick, Barbara (1990). Claudius. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dina Sahyouni, « Le pouvoir critique des modèles féminins dans les Mémoires secrets : le cas de Messaline », in Le règne de la critique. L’imaginaire culturel des Mémoires secrets, sous la direction de Christophe Cave, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2010, p. 151-160.

Notes

Royal titles Preceded by

Milonia CaesoniaEmpress of Rome

41–48Succeeded by

Agrippina the YoungerCategories:- 1st-century births

- 48 deaths

- Ancient Roman women

- 1st-century Romans

- Julio-Claudian Dynasty

- People executed for treason

- People from Rome (city)

- Valerii

- Executed Roman women

- People executed by the Roman Empire

- 1st-century executions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.