- Chiapa de Corzo (Mesoamerican site)

-

Chiapa de Corzo is an archaeological site of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, located in the Central Depression of Chiapas of present-day Mexico. It rose to prominence during the Middle Formative period, becoming a regional center or capital that controlled trade along the Grijalva River.[1] By then, its public precinct had reached 18-20 ha in size, with total settlement approaching 70 ha. The site is believed to have been settled by Mixe–Zoquean speakers, bearers of the Olmec culture that populated the Gulf and Pacific Coasts of southern Mexico. Chiapa de Corzo and a half dozen other western Depression centers appear to have coalesced into a distinct Zoque civilization by 700 BCE, an archaeological culture that became the conduit between late Gulf Olmec society and the early Maya.[2][3][4] Certain Mesoamerican traits such as planned cities, earthen pyramids, E-Group commemorative complexes, cloudy-resist waxy pottery, incensarios, and early logographic writing may have originated in the Zoque region. Chiapa de Corzo and a number of western Depression sites were abandoned by the Late Classic period, a population change that closely coincides with the invasion of a war like group of Mangue-speaking people known as the Chiapanec.[5][6][7]

The modern township of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, founded in Colonial times and after which the site was named, is nearby.

Contents

Site history

The site shows evidence of continual occupation since the Early Formative period (ca. 1200 BCE). The mounds and plazas at the site, however, date to approximately 700 BCE with temples and palaces constructed at the end of the Late Formative or Protoclassic period, between 100 BCE and 200 CE.[8][9] Around 100 BCE, Maya pottery types began to be included in elite burials, although utilitarian ceramics retained traditional patterns.[10] This has suggested to some researchers, that the Maya culture to the east exerted influence or even control over Chiapa de Corzo, although there seems to be a waning of that Maya influence in the first centuries CE.[11] It was during this time that the ancient platform mounds were covered with limestone and stucco.

The site has been heavily encroached upon over the last 70 years with the construction of roads, homes, businesses, utility systems, and a cemetery. The Nestlé company constructed a large milk processessing plant in the center of the ruin in the late 1960s, removing Mound 17, one of the major ceremonial mounds at the site. In recent years, the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) has purchased sections of the site from local land owners. INAH officially opened a small portion of the ruin to tourists on December 8, 2009. The site is currently under investigation by a collaborative team of reasearchers from Brigham Young University, INAH-Chiapas, and Mexico's UNAM (see http://chiapadecorzo.byu.edu/).

Notable finds

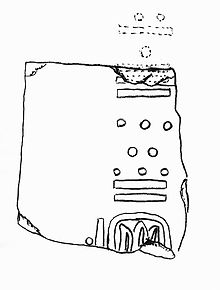

Stela 2, showing the date of 7.16.3.2.13, or December 36 BCE, the earliest Mesoamerican Long Count calendar date yet found.

The oldest Mesoamerican Long Count calendar date yet discovered, December 36 BCE, was found on Stela 2 (which is not a stela at all, but rather a misnamed, inscribed wall panel). All that survives of the original text is the day-name and the digits 7.16.3.2.13.

Chiapa de Corzo is also notable for a pottery sherd containing what is likely Epi-Olmec script. Dated to as early as 300 BCE, this sherd would be the oldest instance of that writing system yet discovered.[12]

The site possesses possibly the earliest example of a Mesoamerican palace complex in Mound 5.[13] This palace was constructed in the first century CE and ritually destroyed a couple centuries later.

More than 250 Formative period burials have been scientifically excavated at Chiapa de Corzo. Many derive from a unique Late Formative burial ground below the Mound 1 plaza. Chiapa de Corzo has the largest and perhaps the best chronologically subdivided Formative period burial sample in southern Mesoamerica.

Chiapa de Corzo has more clay cylinder seals and flat stamps than any other Formative Mesoamerican site, save Tlatilco.[14] Hieroglyphs appear on examples made around 100 BCE.

In 2008, archaeologists discovered a massive Middle Formative Olmec axe deposit at the base of Chiapa de Corzo's Mound 11 pyramid. This deposit dates to around 700 BCE and is the second one of its kind found in Chiapas after San Isidro. It is associated with one of the earliest E-Group astronomical complexes in Mesoamerica.

In April 2010, archaeologists discovered the 2,700-year-old tomb of a dignitary within Mound 11 that is the oldest pyramidal tomb yet discovered in Mesoamerica.[15][16][17][18]

Notes

- ^ Pool, p. 272.

- ^ Clark 2000

- ^ Lowe 1977

- ^ Lowe 1999

- ^ Lowe 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Navarrete 1966.

- ^ Warren, pp. 139-144.

- ^ Lowe, p. 122-123.

- ^ Lowe 1962

- ^ Pool, p. 272.

- ^ See discussion in Pool, p. 272.

- ^ Justeson, p. 2.

- ^ see Lowe 1962

- ^ see Lee 1969

- ^ In an Ancient Mexican Tomb, High Society New York Times, 17 May 2010

- ^ One of Mesoamerica's Oldest Tombs Found Los Angeles Times, 25 May 2010

- ^ BYU-led Team Finds Treasure-filled Tomb in Chiapas Salt Lake Tribune, 21 May 2010

- ^ Pyramid Tomb Found: Sign of a Civilization's Birth? National Geographic Society, 18 May 2010

References

-

- Clark, John E. (2000). "Los pueblos de Chiapas en el Formativo". In Dúrdica Ségota (ed.). Las culturas de Chiapas en el periodo prehispánico. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico.: CONACULTA. pp. 37–85. ISBN 9789706970008. OCLC 52631535. (Spanish)

- Justeson, John S.; and Terrence Kaufman (2001). "Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing and Texts" (PDF). http://www.albany.edu/anthro/maldp/EOTEXTS.pdf. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- Lee, Thomas A. (1969). The Artifacts of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 26. Provo, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University. OCLC 462311120.

- Lowe, Gareth W. (1962). Mound 5 and Minor Excavations, Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 12. Provo, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University. OCLC 962203.

- Lowe, Gareth W. (1977). "The Mixe–Zoque as Competing Neighbors of the Early Maya". In Richard E. W. Adams (ed.). The Origins of Maya Civilization. Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 197–248. ISBN 0826304419. OCLC 2984416.

- Lowe, Gareth W. (1999). Los Zoques Antiguos de San Isidro. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico: Consejo Estatal para las Culturas y Artes de Chiapas. ISBN 9685025665. OCLC 47126036. (Spanish)

- Lowe, Gareth W. (2000). "Chiapa de Corzo". In Susan T. Evans and David Webster (eds.). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: an encyclopedia. London, UK: Garland. ISBN 9780815308874. OCLC 45313588.

- Navarrete, Carlos (1966). The Chiapanec History and Culture. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 16. Provo, Utah, USA: Brigham Young University. OCLC 432388.

- Pool, Christopher (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3. OCLC 68965709.

- Warren, Bruce W. (1977) (Ph.D. dissertation). The Sociocultural Development of the Central Depression of Chiapas, Mexico: Preliminary Considerations. Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA. OCLC 4214390.

Categories:- Mesoamerican sites

- Former populated places in Mexico

- Archaeological sites in Chiapas

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.