- Charlie Taylor

-

For other people named Charles Taylor, see Charles Taylor (disambiguation).

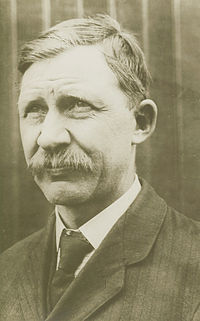

Charles Edward Taylor

"[I] always wanted to learn to fly, but I never did. The Wrights refused to teach me and tried to discourage the idea. They said they needed me in the shop and to service their machines, and if I learned to fly, I'd be gadding about the country and maybe become an exhibition pilot, and then they'd never see me again."(photo: ?)Born May 24, 1868

Cerro Gordo, IllinoisDied January 30, 1956 (aged 87)

CaliforniaOccupation Mechanic, machinist Spouse Henrietta Webbert Charles Edward Taylor (May 24, 1868 – January 30, 1956) built the first aircraft engine used by the Wright brothers and was a vital contributor of mechanical skills in the building and maintaining of early Wright engines and airplanes.

Contents

Biography

Initially, Taylor was hired to fix bicycles, but increasingly took over running of the bicycle business as the Wright brothers spent more time on their aeronautical pursuits.

When it became clear that an off-the-shelf engine with the required power-to-weight ratio was not available in the U.S. for their first engine-driven Flyer, the Wrights turned to Taylor for the job. He designed and built the aluminum water-cooled engine in only six weeks, based partly on rough sketches provided by the Wrights. The cast aluminum block and crankcase weighed 152 pounds (68.9 kg) and were produced at either Miami Brass Foundry or the Buckeye Iron and Brass Works, near Dayton, Ohio. The Wrights needed an engine with at least 8 horsepower (6.0 kW). The engine that Taylor built produced 12.

In 1908 he helped Orville build and prepare the "military Flyer" for demonstration to the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia. On September 17 the airplane crashed due to a shattered propeller, seriously injuring Orville and killing his passenger, Army lieutenant, Thomas Selfridge. Taylor was among the first to reach the crash. He helped lift Selfridge out of the wreckage, then undid Orville's necktie and opened his shirt as doctors in the crowd pushed their way to the scene. Orville and Selfridge were taken away on stretchers. After that,

"...Charlie leaned against an upended wing of the wrecked Flyer, buried his face in his arms, and sobbed. A newspaperman tried to comfort him, but he was past comforting until Dr. Watters assured him that the chances for Orville's recovery were good. Then he pulled himself together and took charge of carting the wrecked Flyer back to its shed."[1]

Both Taylor and Navy Lieutenant George Sweet had been scheduled to make their first flights with Orville that day, but both were bumped in order to accommodate Selfridge who had to leave town for Missouri. Despite this accident Taylor wanted to become a pilot and sought Wilbur and Orville to teach him. The Wrights, fearing for Taylor's safety and possibly accepting Taylor as an 'honorary' Wright brother, vehemently discouraged him. The Wrights understood the risks that came with being a pilot. Had Taylor become a pilot in this early era, the possibility of him perishing in an accident would have been over 70 percent.[citation needed]

In September 1909 Taylor accompanied Wilbur Wright, with a new Model A Flyer, to Governor's Island, New York City. Wilbur was to make several over water flights at the Hudson-Fulton Celebration demonstrating the airplane to millions of New Yorkers and showcasing the new technology of practical flight. Charlie ably assisted Wilbur, though he didn't fly with him. Charlie made sure the engine worked perfectly for Will's daring and dangerous over water trips. The pair also installed a watertight canoe to the Flyer's lower wing for buoyancy just in case of an emergency landing in the Hudson River.

Taylor became a leading mechanic in the Wright Company after it was formed in 1909. When Calbraith Perry Rodgers made his trip from Long Island to California in 1911 in his newly-bought Wright aircraft, he paid Taylor $70 a week (a large sum at the time) to be his mechanic. Taylor followed the flight by train, frequently arriving at the next rendezvous before Rodgers, to make any required repairs and prepare the aircraft for the next day's flight.

Taylor saved enough money from his adventures to buy several hundred acres of farmland near Salton Sea in the southeast corner of California. However the economic climate of the time eventually brought him to poverty. He died penniless and alone in the hospital in 1956.

Although Taylor was largely ignored by history, it would be wrong to think the Wright brothers exploited him or took credit for his achievements. All three of these early pioneers were close friends and Taylor remained in close contact with the last surviving Wright brother, Orville, until Orville's death in 1948. Charlie returned to Dayton in 1936 and he and Orville joined forces with Henry Ford in the planning, moving and restoration of the Wright Family home and one of the Wright Brothers bicycle shops to Ford's Dearborn Michigan heritage establishment on great Americans. Orville had also seen to it that Charlie received an annuity of money so that Charlie would live decently in his later years.

Charlie Taylor died in 1956 aged 87, eight years to the day after friend and employer Orville Wright, and was buried at the Portal of Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Burbank, California, a shrine to aviation history.[2]

Legacy

- The FAA's Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award is named in his honor.

- The Charles Taylor Aviation Maintenance Science Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is named for him.

- Aviation Maintenance Technician Day is observed in 45 U.S. States on May 24, Taylor's birthday.

- television footage from "We Saw It Happen"(1953) with Charlie at age 85.

References

- ^ Fred Howard, "Wilbur and Orville," 1998, p.275

- ^ "C. E. Taylor Laid to Rest With Aviation Pioneers". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 1956. "The body of Charles E. Taylor, the man who built the engine for the world's first airplane, was interred yesterday in the Portal of the Folded Wings at Valhalla Memorial Park, a mausoleum dedicated to aviation pioneer ..."

Further reading

- Article from AMTonline.com

- Howard R. DuFour with Peter J Unitt, The Wright Brother's Mechanician, 1997, ISBN 0-966-9965-0-X. Published by the author. (196 pages, hardback.)

- "Charles E. Taylor: The Man Aviation History Almost Forgot", Air Line Pilot, April 2000, page 18

- "Charlie's Engine", by Tony French in Pilot celebrates 100 years of flying, page 125, Archant Specialist, 2003.

- "My Story", by Charles E. Taylor as told to Robert S. Ball, Air Line Pilot, April 2000, page 22. First published in "Collier's," 1948.

Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation John Bevins Moisant (1868-1910) • Walter Richard Brookins (1889-1953) • Bertrand Blanchard Acosta (1895-1954) • James Floyd Smith (1884-1956) • Charles Edward Taylor (1868-1956) • Winfield Bertrum Kinner (1882-1957) • Elizabeth Lippincott McQueen (1878-1958) • Augustus Roy Knabenshue (1876-1960) • John Franklin Bruce Carruthers (1889–1960) • Mark Mitchell Campbell (1897-1963) • Matilde E. Moisant (1878-1964) • Warren Samuel Eaton (1891-1966) • Carl Browne Squier (1893-1967) • Hilder Florentina Smith (1890-1977) •

Categories:- 1868 births

- 1956 deaths

- American engineers

- Burials at Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery

- Mechanics (trade)

- People from Dayton, Ohio

- People from Piatt County, Illinois

- Wright brothers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.