- Hand axe

-

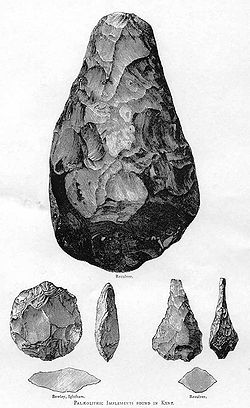

Flint hand axe found in Winchester

A hand axe is a bifacial Stone tool typical of the lower (Acheulean) and middle Palaeolithic (Mousterian), and is the longest-used tool of human history.

Contents

Distribution

Hand axes are found mainly in Africa, Europe and Northern Asia, while South Asia retained flake-industries such as the Hoabinhian.

New archaeological evidence from Baise, China shows that there were also hand axes in eastern Asia.[1][2][3]

Production

Older hand axes were produced by direct percussion with a stone hammer and can be distinguished by their thickness and a sinuous border. Later Mousterian handaxes were produced with a soft billet of antler or wood and are much thinner, more symmetrical and have a straight border.

An experienced flintknapper needs less than 15 minutes to produce a good quality hand axe. A simple hand axe can be made from a beach pebble in less than 3 minutes.

Raw materials

Hand axes are mainly made of flint, but rhyolites, phonolites, quartzites and other rather coarse rocks were used as well. Obsidian, natural volcanic glass, shatters easily and was rarely used.

Shapes

Several basic shapes, like cordate, oval, or triangular have been distinguished, but their chronological significance is not agreed upon.

Function

As most hand axes have a sharp border all around, there is no firm agreement about their use. Interpretations range from cutting and chopping tools to digging implements, flake cores, even the use in traps and a purely ritual significance (such as courting behaviour). The current majority scientific view of their use however, is some form of chopping or tool for general purpose use, probably for cutting meat and extracting bone marrow (which would explain the pointed end) and general hacking through bone and muscle fiber. Experiments at Boxgrove appear to back this up.

H.G. Wells proposed in 1899 that handaxes were used as missile weapons to hunt prey[4] - an interpretation supported by William H. Calvin. Calvin maintains that some of the rounder examples could have served as "killer frisbees" meant to be thrown at a herd of animals at a water hole so as to stun one of them. There are few indications of hand axe hafting, and some artifacts are far too large for that. However a thrown hand axe would not usually have penetrated deeply enough to cause very serious injuries. Additionally many hand axes are very small. There is very little evidence of impact damage in most handaxes.

Tony Baker suggested that the hand axe was not a tool, but a core from which flakes had been removed and used as tools(http://www.ele.net/acheulean/handaxe.htm flake core] theory). However, hand axes are often found with retouch such as sharpening or shaping, casting doubt on this idea.

Other theories suggest the shape is part tradition and partly a byproduct of the way it is manufactured. Since many early hand axes appear to be made from simple rounded pebbles (from river or beach deposits), it is necessary to detach a 'starting flake', often much larger than the rest of the flakes (due to the oblique angle of a rounded pebble requiring greater force to detach it), thus creating an asymmetry in the hand axe. When the asymmetry is corrected by removing extra material from the other faces, a trend toward a more pointed (oval) form factor is achieved. (Knapping a completely circular hand axe requires considerable correction of the shape.) Studies in the 1990s at Boxgrove, in which a butcher attempted to cut up a carcass with a hand axe, revealed that the hand axe was perfect for getting at bone marrow.

Marek Kohn and Steven Mithen have independently arrived at the explanation that symmetric handaxes have been favored by sexual selection as fitness indicators.[5] Kohn in his book As we know it wrote that the handaxe is "a highly visible indicator of fitness, and so becomes a criterion of mate choice."[6] Evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller follows on their example and has said that handaxes have characteristics which make them suitable for being subject to sexual selection forces, such as that they were made for over a million years throughout Africa, Europe and Asia, they were made in large numbers, and most were impractical for utilitarian use. He says that a single design persisting across such a span of time and space cannot be explained by cultural imitation and draws a parallel between bowerbirds' bowers (built to attract potential mates and used only during courtship) and Pleistocene hominids' handaxes. He calls handaxe building a "genetically inherited propensity to construct a certain type of object." He discards the idea that they were used as missile weapons as there were more efficient weapons at the time, such as javelins, and although he accepts that some handaxes may have been used for practical reasons, he agrees with Kohn and Mithen who have shown that many handaxes show a considerable degree of skill, design and symmetry beyond the demands for utility, some were too big (such as the handaxe found in Furze Platt, England which is over a foot long) or too small (less than two inches, therefore of little practical use), they feature symmetry far beyond practical use and show evidence for excessive attention to form and finish. Miller thinks that the most important clue is that most handaxes show no signs of use or evidence of edge wear under electron microscopes. Furthermore, handaxes can be good handicaps in Amotz Zahavi's handicap principle theory: the learning costs are high, there are risks of injury, they require physical strength, hand-eye coordination, planning, patience, pain tolerance, and resistance to infection from cuts and bruises when making or using such a handaxe. [7]

References

- ^ http://www.kaogu.cn/en_kaogu/show_News.asp?id=338 1

- ^ 2

- ^ 3

- ^ Kohn, Marek (1999). As We Know it: Coming to Terms with an Evolved Mind. Granta Books. p. 59. ISBN 9781862070257.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2005). The Singing Neanderthals. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 188–191.

- ^ Kohn, Marek (1999), p.137

- ^ Miller, Geoffrey (2001). The Mating Mind: How sexual choice shaped the evolution of human nature. London: Vintage. pp. 288–291. ISBN 9780099288244.

Bibliography

- A. S. Barnes/H. H. Kidder, Differentes techniques de débitage à La Ferrassie. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Franç. 33, 1936, 272-288.

- C. A Bergmann/M. B. Roberts, Flaking technology at the Acheulean site of Boxgrove, West Sussex, England. Rev. Arch. Picardie, Numero Special, 1-2, 1988, 105-113.

- F. Bordes, Le couche Moustérienne du gisement du Moustier (Dordogne): typologie et techniques de taille. Soc. Préhist. Française 45, 1948, 113-125.

- F. Bordes, Observations typologiques et techniques sur le Perigordien supérieur du Corbiac (Dordogne). Soc. Préhist. Française 67, 1970, 105-113.

- F. Bordes, Le débitage levallois et ses variantes. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 77/2, 1980, 45-49.

- P. Callow, The Olduvai bifaces: technology and raw materials. In: M. D. Leakey/D. A. Roe, Olduvai Gorge Vol. 5. (Cambridge 1994) 235-253.

- H. L. Dibble, Reduction sequences in the manufacture of Mousterian implements in France. In: O. Soffer (Hrsg.), The Pleistocene of the Old world, regional perspectives (New York 1987).

- P. R. Fish, Beyond tools: middle palaeolithic debitage: analysis and cultural inference. J. Anthr. Res. 1979, 374-386.

- F. Knowles, Stone-Worker’s Progress (Oxford 1953).

- Marek Kohn/Steven Mithen Axes, products of sexual selection?, Antiquity 73, 1999, 518-26.

- K. Kuman, The Oldowan Industry from Sterkfontein: raw materials and core forms. In: R. Soper/G. Pwiti (Hrsg.), Aspects of African Archaeology. Papers from the 10th Congress of the Pan-African Association for Prehistory and Related Studies. Univ. of Zimbabwe Publications (Harare 1996) 139-146.

- J. M. Merino, Tipología lítica. Editorial Munibe 1994. Suplemento, (San Sebastián 1994). ISSN 1698-3807.

- H. Müller-Beck, Zur Morphologie altpaläolithischer Steingeräte. Ethnogr.-Archäol.-Zeitschr. 24, 1983, 401-433.

- M. Newcomer, Some quantitative experiments in handaxe manufacture. World Arch. 3, 1971, 85-94.

- Th. Weber, Die Steinartefakte des Homo erectus von Bilzingsleben. In: D. Mania/Th. Weber (Hrsg.), Bilzingsleben III. Veröff. Landesmus. Vorgesch. Halle 39, 1986, 65-220.

External links

Categories:- Archaeological artefact types

- Axes

- Lithics

- Primitive weapons

- Paleolithic

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.