- Equine forelimb anatomy

-

Equine forelimb anatomy

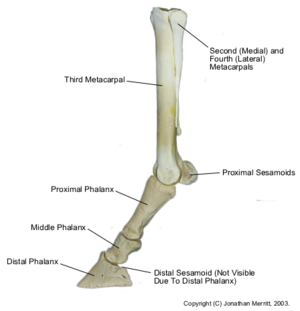

The bones and joints of the equine forelimb distal to the wrist (or carpus): The fetlock (metacarpophalangeal joint) is located between the cannon bone (third metacarpal) and the long pastern bone (proximal phalanx). The pastern joint (proximal interphalangeal joint) is located between the long pastern bone and the short pastern bone (middle phalanx). The coffin joint (distal interphalangeal joint) is located between the short pastern bone and the coffin bone (distal phalanx).

Shock absorption of the pastern The equine forelimb (also referred to as the front limb, rostral limb, cephalad limb or thoracic limb) of the horse is attached to the trunk of the animal by purely muscular connections (the serratus ventralis, trapezius, rhomboideus, latissimus dorsi, brachiocephalicus, subclavius and pectoralis muscles). This is in contrast to the forelimbs of several other vertebrates, including humans, who have skeletal attachments (the coracoid and clavicle bones).

During locomotion, the forelimb functions primarily for weight-bearing rather than propulsion and supports the forehand of the horse. In the standing horse, the forelimbs together support approximately 60% of the weight of the horse, and this pattern is carried over to locomotion, where the forelimb props the weight of the horse, while forward momentum is generated by the hind limbs (Merkens et al., 1993; Merkens and Schamhardt, 1994). As the horse moves, increasing impulsion shifts the horse's weight to the hindquarters.

Contents

Bones of the distal forelimb

Metacarpal bones

The equine forelimb contains three metacarpal bones. These are analogous to the bones within the human palm. The large third metacarpal (informally the cannon bone or shin bone) provides the major support of the body weight. The smaller second and fourth metacarpals are positioned medially and laterally respectively, toward the palmar side of the third metacarpal. These smaller metacarpals are often called splint bones. The second and fourth metacarpals terminate distally in small residual swellings, (buttons) which can be palpated on a living horse. The second and fourth metacarpals are joined to the third metacarpal by fibrous tissue, and occasionally by ossified bridges of bone, which often form after trauma to the region.

Proximal sesamoids

The proximal sesamoids are paired bones which lie palmar to the metacarpophalangeal joint (the fetlock joint). These bones are joined to each other by a strong intersesamoidean ligament. These bones are sesamoids of the interosseous ligament (the suspensory ligament) of the forelimb.

Proximal phalanx

The proximal phalanx or long pastern bone lies immediately distal to the third metacarpal bone, with which it articulates to form the condylar metacarpophalangeal joint (fetlock joint). This joint undergoes large motion in extension (this motion is sometimes called dorsiflexion) during fast locomotion.

Middle phalanx

The middle phalanx or short pastern bone lies distal to the proximal phalanx, forming the proximal interphalangeal joint (the pastern joint). This joint undergoes relatively little movement during locomotion (Degueurce et al., 2001; Crevier-Denoix et al., 2001), although there is evidence to suggest that what little motion it does experience is of quite large importance (Wilson et al., 2001; Ratzlaff and White, 1989).

Distal phalanx

Close up of the coffin bone

Close up of the coffin bone

The distal phalanx or third phalanx (coffin bone), is the most distal bone of the forelimb, and lies completely within the hoof capsule. The distal phalanx articulates with both the middle phalanx and the distal sesamoid, forming the distal interphalangeal joint (the coffin joint).

Distal sesamoid

The distal sesamoid, or navicular bone (note that "navicular bone" is acceptable in a veterinary context), articulates closely with the distal phalanx, to which it is connected by the impar ligament of the navicular bone. The impar ligament is very strong and permits relatively little motion between the navicular bone and the distal phalanx.

References

- Crevier-Denoix, N., Roosen, C., Dardillat, C., Pourcelot, P., Jerbi, H., Sanaa, M. and Denoix, J.-M. (2001) Effects of heel and toe elevation upon the digital joint angles in the standing horse. Equine Vet J, Suppl 33:74-78.

- Degueurce, C., Chateau, H., Jerbi, H., Crevier-Denoix, N., Pourcelot, P., Audigie, F., Pasqui-Boutard, V., Geiger, D. and Denoix, J.-M. (2001) Three-dimensional kinematics of the proximal interphalangeal joint: effects of raising the heels or the toe. Equine Vet J, Suppl 33:79-83.

- Merkens, H.W., Schamhardt, H.C., van Osch, G.J.V.M. and van den Bogert, A.J. (1993) Ground reaction force patterns of Dutch Warmblood horses at normal trot. Equine Vet J 25(2):134-137.

- Merkens, H.W. and Schamhardt, H.C. (1994) Relationships between ground reaction force patterns and kinematics in the walking and trotting horse. Equine Vet J, Suppl 17:67-70.

- Ratzlaff, M.H. and White, K.K. (1989) Some biomechanical considerations of navicular disease. J Equine Vet Sci 9(3):149-153.

- Wilson, A.M., McGuigan, M.P., Fouracre, L. and MacMahon, L. (2001) The force and contact stress on the navicular bone during trot locomotion in sound horses and horses with navicular disease. Equine Vet J 33(2):159-165.

Further reading

See also

External links

Categories:- Horse anatomy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.