- Albany Congress

-

"Albany Conference" redirects here. For the early Millerite meeting, see Adventism#Albany Conference.

Delegates converse outside the Stadt Huys during the Albany Congress.

Delegates converse outside the Stadt Huys during the Albany Congress.

The Albany Congress, also known as the Albany Conference and "The Conference of Albany" or "The Conference in Albany", was a meeting of representatives from seven of the thirteen British North American colonies in 1754 (specifically, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island). Representatives met daily at Albany, New York from June 19 to July 11 to discuss better relations with the Indian tribes and common defensive measures against the French. Delegates did not view themselves as builders of an American nation; rather, they were colonists with the more limited mission of pursuing a treaty with the Mohawks.[1]

Contents

Previous colonial unions

The Albany Congress was the first time in the 18th century that colonial representatives met to discuss some form of formal union. Some New England colonies had in the 17th century formed a loose association, called the New England Confederation, principally for purposes of defense. The Dominion of New England was imposed as a unifying government on the colonies between the Delaware River and Penobscot Bay by King James II in the 1680s, and was dissolved in 1689.

History of the meeting

The Albany delegates spent most of their time debating Benjamin Franklin's Albany Plan of union. It would have created a unified colonial entity. The delegates voted approval of a plan that called for a union of 12 colonies, with a president appointed by the Crown. Each colonial assembly would send 2 to 7 delegates to a "grand council" that would have legislative powers. The Union would have jurisdiction over Indian affairs.

The plan was rejected by the colonies, which were jealous of their powers, and by the Colonial Office, which wanted a military command. However, it formed much of the basis for the later American governments established by the Articles of Confederation of 1777 and the Constitution of 1787. Franklin himself later speculated that had the 1754 plan been adopted, the colonial separation from England might not have happened so soon.

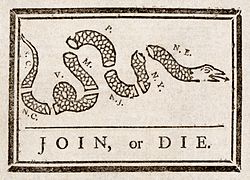

The episode has achieved iconic status as presaging the formation of the United States of America in 1776, and is often illustrated with Franklin's famous snake cartoon,"Join or Die!" Historians generally reject the popular notion that the delegates were inspired by the Iroquois Confederation.[2]

Plan of Union

Benjamin Franklin proposed a plan for uniting the seven colonies that greatly exceeded the scope of the congress. The original plan was heavily debated by all who attended the conference including the young lawyer Benjamin Chew.[3] Numerous modifications were also proposed by Thomas Hutchinson, who would later become Governor of Massachusetts, and the plan proceeded to be passed unanimously. The plan was submitted as a recommendation but was rejected by the legislatures of the individual seven colonies since it would remove some of their existing powers. The plan was never even sent to London for approval.

Benjamin Franklin's cartoon, encouraging support for the Congress

Benjamin Franklin's cartoon, encouraging support for the Congress

The Union plan included all the British North American colonies, except Delaware and Georgia. The plan called for a single executive (President-General) to be appointed by the King, who would be responsible for Indian relations, military preparedness, and execution of laws regulating various trade and financial activities. It called for a Grand Council to be selected by the colonial legislatures where the number of delegates would be based on the taxes paid by each colony. Even though rejected, some features of this plan were later adopted in the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.

Benjamin Franklin said of the plan in 1789:

On Reflection it now seems probable, that if the foregoing Plan or some thing like it, had been adopted and carried into Execution, the subsequent Separation of the Colonies from the Mother Country might not so soon have happened, nor the Mischiefs suffered on both sides have occurred, perhaps during another Century. For the Colonies, if so united, would have really been, as they then thought themselves, sufficient to their own Defence, and being trusted with it, as by the Plan, an Army from Britain, for that purpose would have been unnecessary: The Pretences for framing the Stamp-Act would not then have existed, nor the other Projects for drawing a Revenue from America to Britain by Acts of Parliament, which were the Cause of the Breach, and attended with such terrible Expence of Blood and Treasure: so that the different Parts of the Empire might still have remained in Peace and Union.Participants

Twenty-one representatives of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire attended the Congress. James DeLancey, acting Governor of New York, as host governor, was the Chairman. Peter Wraxall served as Secretary to the Congress.

Delegates included:

- Connecticut: William Pitkin, Roger Wolcott, Jr., Elisha Williams

- (Also present from Connecticut was John Lydius, who did not represent the colony. Lydius was a land agent and speculator hired by the Susquehannah Company to purchase land in the Wyoming Valley from the Iroquois. In that respect, Lydius' role is comparable to a modern lobbyist who may attend a government function in order to advance his client's interest.)

- Maryland: Abraham Barnes, Benjamin Tasker, Jr.

- Massachusetts: Thomas Hutchinson, Oliver Partridge

- New Hampshire: Meshech Weare, Theodore Atkinson

- New York: James DeLancey, William Johnson, Philip Livingston

- Pennsylvania: Secretary Benjamin Chew, Benjamin Franklin, William Franklin, Conrad Weiser

- Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins

An apparently complete list is given at Early Recognized Treaties With American Indian Nations

See also

- History of the United States Constitution

- History of Albany, New York

- Great Britain in the Seven Years War

References

- General

- Alden, John R. "The Albany Congress and the Creation of the Indian Superintendencies," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Sep., 1940), pp. 193–210 in JSTOR

- Bonomi, Patricia, A Factious People, Politics and Society in Colonial America, 1971, ISBN 0-231-03509-8

- Brands, H.W. The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2002) excerpt and text search

- McAnear, Beverly. "Personal Accounts of the Albany Congress of 1754," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Mar., 1953), pp. 727–746 in JSTOR, primary documents

- Timothy J. Shannon, Indians and Colonists at the Crossroads of Empire: The Albany Congress of 1754 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2000).

- Specific

External links

- Full text of the Albany Plan of Union

- Summary of the Albany Congress

- The Albany Congress of 1754, prints and drawings from the Emmet Collection of Manuscripts Etc. Relating to American History in the New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

"Albany Convention of 1754". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Albany Convention of 1754". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. "Albany Congress". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Albany Congress". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

Categories:- French and Indian War

- History of the Thirteen Colonies

- 1754 in the Thirteen Colonies

- History of Albany, New York

- Pre-state history of New York

- Connecticut: William Pitkin, Roger Wolcott, Jr., Elisha Williams

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.