- Walter Dandy

-

Walter Edward Dandy, M.D. (April 6, 1886 – April 19, 1946) was an American neurosurgeon and scientist. He is considered one of the founding fathers of neurosurgery, along with Victor Horsley (1857-1916) and Harvey Cushing (1869-1939). Dandy is credited with numerous neurosurgical discoveries and innovations, including the description of the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, surgical treatment of hydrocephalus, the invention of air ventriculography and pneumoencephalography, the description of brain endoscopy, the establishment of the first intensive care unit (Fox 1984, p. 82), and the first clipping of an intracranial aneurysm, which marked the birth of cerebrovascular neurosurgery. During his 40-year medical career, Dandy published five books and more than 160 peer-reviewed articles while conducting a full-time, ground-breaking neurosurgical practice in which he performed during his peak years about 1000 operations per year (Sherman et al. 2006). He was recognized at the time as a remarkably fast and particularly dextrous surgeon. Dandy was associated with the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Hospital his entire medical career. The importance of his numerous contributions to neurosurgery in particular and to medicine in general has increased as the field of neurosurgery has evolved.

Contents

Early Life and Medical Training

Dandy was the only son of John Dandy, a railroad engineer, and Rachel Kilpatrick, who were immigrants from Lancashire, England, and Armagh, Ireland, respectively. Dandy graduated in 1903 from Summitt High School in Sedalia, Missouri, as class valedictorian, and then graduated in 1907 from the University of Missouri. In September 1907, he enrolled in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as a second year student. (He had started medical studies during his junior year in college and accumulated enough credits to skip the first year of medical school at Johns Hopkins.) Dandy graduated from medical school in the spring of 1910 at the age of 24, and became the sixth appointee to the Hunterian Laboratory of Experimental Medicine under Harvey W. Cushing from 1910-1911. In 1911, he earned a Master of Arts degree for his work in the Hunterian Laboratory, and went on to join the Johns Hopkins Hospital surgical housestaff for one year as Cushing's Assistant Resident (1911-1912). Dandy completed his general surgery residency at the Johns Hopkins Hospital under William S. Halsted in 1918. (He had been appointed Halsted's Chief Resident in 1916.) While Dandy was introduced to the nascent field of neurosurgery by Cushing, it was George J. Heuer who completed Dandy's neurosurgical training after Cushing's departure for the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston in September 1912. Heuer had graduated from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1908, worked as Cushing's first Assistant Resident from 1908-1909, and served as Halsted's Chief Resident from 1911 to 1914.

Dandy joined the staff of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1918 and immediately focused his energies on the surgical treatment of disorders of the brain and spinal cord. When Heuer left Hopkins in 1922 to become the head of surgery at the University of Cinicinnati, Dandy remained as the only neurosurgeon at the Johns Hopkins Hospital until his death in that hospital in 1946.

Scientific and Clinical Contributions

Contributions to Pediatric Neurosurgery

Dandy's first scientific contribution was the detailed anatomical description of a 2 mm human embryo in Franklin P. Mall's collection. This paper was published in 1910, five months before he graduated from medical school. In 1911 and 1913, he described the blood supply and nerve supply, respectively, of the pituitary gland. In 1913 and 1914, Dandy and Kenneth D. Blackfan published two landmark papers on the production, circulation, and absorption of CSF in the brain and on the causes and potential treatments of hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus is the buildup of CSF within the brain, an often lethal condition if left untreated. They described two forms of hydrocephalus, namely "obstructive" and "communicating," thus establishing a theoretical framework for the rational treatment of this condition. This work is regarded by many as one of the finest pieces of surgical research ever done. Indeed, Halsted reportedly told Edwards A. Park that "Dandy will never do anything equal to this again. Few men make more than one great contribution to medicine." (Fox 1984, p. 36) Dandy, however, would prove to be one of these "few men." Modern pediatric neurosurgeons devote most of their time to the management of hydrocephalus. Currently, the Walter E. Dandy Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh, Ian F. Pollack [1], is a pediatric neurosurgeon and the chief of the Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery.

The Dandy-Walker malformation is a congenital malformation associated with hydrocephalus. In 1921 Dandy reported a case of hydrocephalus caused by obstruction of outflow of CSF from the fourth ventricle. In 1944 A. Earl Walker (who eventually became chairman of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins) described a similar case of congenital closure of the outflow of the fourth ventricle. This congenital anomaly became known as the Dandy-Walker cyst. It is associated with closure of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie (the outflow openings of the fourth ventricle), atrophy of the cerebellum and cerebellar vermis, dilation of the fourth ventricle, hydrocephalus, and often atrophy of the corpus callosum.

Contributions to Neuroradiology

In 1918 and 1919 Dandy published his landmark papers on air ventriculography and the associated technique of pneumoencephalography. For this contribution he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1933 by Hans Christian Jacobaeus, Chairman of the Nobel Committee of the Karolinska Institute (Ligon 1998, p.607). Ventriculography and pneumoencephalography allowed neurosurgeons for the first time to visualize brain lesions on x-rays. To accomplish this, CSF in the ventricles and subarachnoid space was replaced with air injected either directly into the ventricles (ventriculography) or into the lumbar subarachnoid space (pneumoencephalography). As a general surgeon, Dandy was aware of the ability of free air in the peritoneal cavity to outline the abdominal contents. He published a paper on this radiographic phenomenon ("pneumoperitoneum") in 1919 based on a clinical observation he had made in 1917. In 1918, the year that he finished his residency, he published the paper on air ventriculography. The importance of this advance cannot be overstated. Samuel J. Crowe described it as "the greatest single contribution ever made to brain surgery." (Fox 1984, p.43) Gilbert Horrax stated:

"The importance of this diagnostic method, ... for the more accurate localization of many growths whose situation could not be ascertained with absolute exactness, can hardly be overemphasized. It brought immediately into the operable field at least one third more brain tumors than could be diagnosed and localized previously by the most refined neurological methods." (Fox 1984, p.45)

Air ventriculography, however, had the limitation that a burr hole had to be drilled in the skull to pass the needle into the ventricular system. In 1919, Dandy published a less invasive technique that he labelled pneumoencephalography. In this procedure, air was injected into the subarachnoid space of the lumbar spinal canal and then the air bolus was maneuvered into the subarachnoid space around the brain and eventually into the ventricles by changing the patient's position. Ventriculography and pneumoencephalography allowed neurosurgeons to accurately identify the location and size of tumors and other lesions and then accurately target their operative approach. This technique remained the single most important way of localizing brain lesions until the introduction of computerized tomography (CT) scanning in the 1970s.

Contributions to Operative Neurosurgery

Already by 1919, barely one year after finishing his surgical training, Dandy was recognized arguably as the premier surgeon at Johns Hopkins. Abraham Flexner, who was intimately familiar with the workings of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and in 1910 had produced the Flexner Report on American and Canadian Medical Education, wrote on January 30, 1919:

"The general sentiment hereabouts is that Dandy is the man for surgery. ... As Dr. Halsted comes about very little now, Dandy is carrying the whole thing, and, as far as I can judge, does it admirably. He has the devotion and confidence of all his associates and treats them in a really beautiful way ..." (Fox 1984, p.54)

Dandy's surgical innovations proceeded at an astounding rate as he became increasingly comfortable operating on the brain and spinal cord. He described in 1921 an operation for the removal of tumors of the pineal region, in 1922 complete removal of tumors of the cerebellopontine angle (namely acoustic neuromas), in 1922 the use of endoscopy for the treatment of hydrocephalus ("cerebral ventriculoscopy"), in 1925 sectioning the trigeminal nerve at the brainstem to treat trigeminal neuralgia, in 1928 treatment of Ménière's disease (recurrent vertiginous dizziness) by sectioning the vestibular nerves, in 1929 removal of a herniated disc in the spine, in 1930 treatment of spasmodic torticollis, in 1933 removal of the entire cerebral hemisphere ("hemispherectomy") for the treatment of malignant tumors, in 1933 removal of deep tumors within the ventricular system, in 1935 treatment of carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCFs), in 1938 ligation or "clipping" of an intracranial aneurysm, and in 1941 removal of orbital tumors. Remarkably, these operations continue to be performed today essentially in the same form described by Dandy. As medicine progresses, other contributions by Dandy have been replaced by alternative therapies. For instance, in 1943, Dandy published an operation for treatment of essential hypertension by sectioning the sympathetic nerves, but nowadays hypertension is treated with medications.

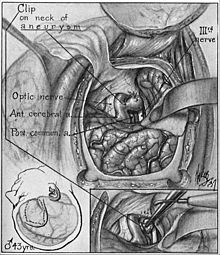

Contributions to Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery

Dandy's 1938 description of surgery for clipping of an intracranial aneurysm is particularly important because it marked the birth of the subspecialty of cerebrovascular neurosurgery. An aneurysm is a sac that grows from the wall of an artery in the brain. When an aneurysm ruptures, 50% of patients die immediately and the remaining are similarly expected to die if the aneurysm ruptures again, as it is likely to do. In 1937, a ruptured intracranial aneurysm was a uniformly fatal condition. On March 23, 1937, Dandy performed a frontotemporal craniotomy (which he had learned from Heuer) and placed a hemostatic clip on the neck of a posterior communicating artery region aneurysm arising from the internal carotid artery. The technical prowess involved in carrying out this operation successfully can not be overstated, particularly without the benefit of the surgical microscope for magnification. Even today this type of surgery is arguably the most complex and riskiest procedure done by neurosurgeons. This represented the first time that a vascular problem of the brain was treated successfully with surgery in a planned fashion. This experience led Dandy in the later part of his career to treat successfully a variety of vascular problems of the brain in addition to aneurysms, such as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs), carotid cavernous fistulas (CCFs), and cavernous malformations. In 1944, two years prior to his death, Dandy published a book entitled Intracranial Arterial Aneurysms in which he summarized his experience with these treacherous and technically formidable lesions. Currently, the Walter E. Dandy Professor of Neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, Rafael J. Tamargo [2][3], is a cerebrovascular neurosurgeon and the director of the Division of Cerebrovascular Neurosurgery [4], the field created by Dandy.

Dandy's "Brain Team"

Dandy established at the Johns Hopkins Hospital a clinical service that served the dual purpose of delivering outstanding care to his patients and also of training surgical residents and fellows to become neurosurgeons. This became a highly orchestrated and efficient system that allowed Dandy to perform over 1000 operations annually (excluding ventriculograms) and produced 12 neurosurgeons who then carried on Dandy's tradition. Dandy's service was known as the "Brain Team." By 1940, Dandy's Brain Team consisted of a resident, an assistant resident, a surgical intern, a full-time scrub nurse, a full-time nurse anesthetist, an assistant scrub nurse, a circulating nurse, a part-time nurse anesthetist, a full-time orderly, and Dandy's secretary. The resident and assistant resident each spent two years (out of their eight-year general surgery residency) on the Brain Team. (Sherman et al. 2006)

Personal life

In 1923, five years after finishing his arduous surgical training, Dandy started to focus on his personal life. Throughout his training he had remained close to his parents, with whom he corresponded at times daily. Dandy made arrangements for his parents to move to Baltimore in early 1911, one year after he finished medical school. Dandy met his future wife, Sadie E. Martin, in 1923, got married on October 1, 1924, and had four children: Walter Edward Jr. (born 1925), Mary Ellen (1927), Kathleen Louise (1928), and Margaret Martin (1935). He described his family relations as "the finest thing in life." Fox 1984, p. 118) He vacationed with his family regularly, when his children's school schedule allowed. He rarely traveled, however, for professional meetings, and preferred to stay in Baltimore close to his family and work. Upon being invited to join the Society of Neurological Surgeons as a charter member, he wrote to Cushing on June 30, 1921, that he was "very averse to joining societies of all kinds because I feel they are more social than beneficial and I cannot spare the time for them." (Fox 1984, p. 73)

Irving J. Sherman, who trained in neurosurgery under Dandy from 1941 to 1943, addressed this in his recollections:

"Historians are uniformly effusive in praise of Dandy's research and surgery, but they are less kind with regard to his personality, no doubt because they did not know him personally ... Dandy never charged schoolteachers, clergy, other medical workers, or patients who had no money to pay. At times, he also gave money to patients to help them with the expense of coming to Baltimore. ... There were stories of Dandy being dictatorial and demanding perfect service for his patients, and these were true. There were other stories, also true, of Dandy having outbursts of temper when "things did not go right in the operating room," firing assistant residents, scolding personnel, and occasionally throwing an instrument. However, during my time on the general surgery and neurosurgery housestaff (1940-1943), I never observed such incidents. ... although Dandy was at times dictatorial and demanding, his actions made it obvious that he care deeply for our welfare, although not about how hard we worked." (Sherman et al. 2006)

Outside the hospital, Dandy's warmth and playfulness were evident in his interactions with his family, friends, and colleagues. (Tamargo 2002, p. 101). His personality is best summarized in his obituary in the Baltimore Sun of April 20, 1946:

"... Gruff of manner, hot of temper, and endowed with a tongue as sharp as his instruments, he exacted awe, respect, and the hardest kind of work from his students. ... And when they got to know him well, they found beneath the hard exterior - as is not uncommon in men of such temperament - a deep vein of tenderness."

Dandy enjoyed excellent health most of his life, except for November and December 1919, the year after completing his residency, when he became bedridden with sciatic neuralgia. (Fox 1984, p. 54) On April 1, 1946, five days before his 60th birthday, Dandy was hospitalized with a heart attack. He asked his secretary to help him prepare his will, which he signed on April 9 while in the hospital. He was discharged home, but suffered a second heart attack on April 18. He was taken again to the Johns Hopkins Hospital where he died on April 19. (Fox 1984, p. 221) He was buried in Druid Ridge Cemetery in Pikesville, Maryland.

See also

References

- Dandy Marmaduke, ME. Walter Dandy. The Personal Side of a Premier Neurosurgeon, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2002.

- Fox, WL. Dandy of Johns Hopkins. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland, 1984.

- Ligon, BL. "The mystery of angiography and the "unawarded" Nobel prize: Egas Moniz and Hans Christian Jacobaeus." Neurosurgery 43: 602-611, 1998.

- Sherman, IJ, Kretzer, RM, Tamargo, RJ. "Personal recollections of Walter E. Dandy and his brain team." Journal of Neurosurgery 105: 487-93, 2006.

- Tamargo, RJ, and Brem, H. "Editorial Comment: Marriage, Family, and Career (1923-1946)." In Walter Dandy. The Personal Side of a Premier Neurosurgeon, Dandy Marmaduke, ME, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2002.

External links

- doctor/447 at Who Named It?

- Walter E. Dandy, M.D., Professorship at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine[5]

- Walter E. Dandy, M.D., Professorship at the University of Pittsburgh[6]

- Rafael J. Tamargo, M.D., Walter E. Dandy Professor of Neurosurgery at the Johns Hopkins University[7][8]

- Ian F. Pollack, M.D., Walter E. Dandy Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh[9]

Categories:- 1886 births

- 1946 deaths

- University of Missouri alumni

- Johns Hopkins School of Medicine alumni

- American physicians

- American surgeons

- American scientists

- People from Sedalia, Missouri

- Johns Hopkins Hospital physicians

- Neurosurgeons

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.