- Symphony No. 2 (Mahler)

-

The Symphony No. 2 by Gustav Mahler, known as the Resurrection, was written between 1888 and 1894, and first performed in 1895. Apart from the Eighth Symphony, this symphony was Mahler's most popular and successful work during his lifetime. It is his first major work that would eventually mark his lifelong view of the beauty of afterlife and resurrection. In this large work, the composer further developed the creativity of "sound of the distance" and creating a "world of its own", aspects already seen in his First Symphony. The work lasts around eighty to ninety minutes.

Contents

Origin

Mahler completed what would become the first movement of the symphony in 1888 as a single-movement symphonic poem called Totenfeier (Funeral Rites). Some sketches for the second movement also date from that year. Mahler wavered five years on whether to make Totenfeier the opening movement of a symphony, although his manuscript does label it as a symphony. In 1893, he composed the second and third movements.[1] The finale was the problem. While thoroughly aware he was inviting comparison with Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 (both use a chorus as the centerpiece of a much longer final movement, which begins with references to the earlier movements), Mahler knew he wanted a vocal final movement. Finding the right text for this movement proved long and perplexing.[2]

When Mahler took up his appointment at the Hamburg Opera in 1891, he found the other important conductor there to be Hans von Bülow, who was in charge of the city's symphony concerts. Bülow, not known for his generosity, was impressed by Mahler. His support was not diminished by his failure to like or understand Totenfeier when Mahler played it for him on the piano. Bülow told Mahler that Totenfeier made Tristan und Isolde sound to him like a Haydn symphony. As Bülow's health worsened, Mahler substituted for him. Bülow's death in 1894 greatly affected Mahler. At the funeral, Mahler heard a setting of Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock's Die Auferstehung (The Resurrection). "It struck me like lightning, this thing," he wrote to conductor Anton Seidl, "and everything was revealed to me clear and plain." Mahler used the first two verses of Klopstock's hymn, then added verses of his own that dealt more explicitly with redemption and resurrection.[3] He finished the finale and revised the orchestration of the first movement in 1894, then inserted the song Urlicht (Primal Light) as the penultimate movement. This song was probably written in 1892 or 1893.[1]

Mahler devised a narrative programme for the work, which he told to a number of friends. In this programme, the first movement represents a funeral and asks questions such as "Is there life after death?"; the second movement is a remembrance of happy times in the life of the deceased; the third movement represents a view of life as meaningless activity; the fourth movement is a wish for release from life without meaning; and the fifth movement – after a return of the doubts of the third movement and the questions of the first – ends with a fervent hope for everlasting, transcendent renewal, a theme that Mahler would ultimately transfigure into the music of his sublime Das Lied von der Erde.[4]

Publication

The work was first published in 1897 by Friedrich Hofmeister. The rights were transferred to Josef Weinberger shortly thereafter, and finally to Universal Edition, which released a second edition in 1910. A third edition was published in 1952, and a fourth, critical edition in 1970, both by Universal Edition. As part of the new complete critical edition of Mahler's symphonies being undertaken by the Gustav Mahler Society, a new critical edition of the Second Symphony was produced as a joint venture between Universal Edition and the Kaplan Foundation. Its world premiere performance was given on 18 October 2005 at the Royal Albert Hall in London with Gilbert Kaplan conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.[5]

Reproductions of earlier editions have been released by Dover and by Boosey & Hawkes. The Kaplan Foundation published an extensive facsimile edition with additional materials in 1986.

1899 saw the publication of an arrangement by Bruno Walter for piano four-hands.

Instrumentation

The symphony is written for an orchestra, a mixed choir, two soloists (soprano and contralto), organ, and an offstage ensemble of brass and percussion. The use of two tam-tams, one pitched high and one low, is particularly unusual; the end of the last movement features them struck in alternation repeatedly.

- Woodwinds

- 4 Flutes (all four doubling Piccolos)

- 4 Oboes (3rd and 4th oboe doubling English Horns)

- 3 Clarinets in B-flat, A, C (3rd clarinet doubling Bass Clarinet)

- 2 E-flat Clarinets (2nd E-flat clarinet doubling 4th clarinet in B-flat and A) [6]

- 4 Bassoons (3rd and 4th Bassoon doubling Contrabassoon)[7]

- Brass

- 10 French Horns in F, four (7-10) also used offstage (preferably more)[8]

- 8-10 Trumpets in F and C, four to six used offstage [9]

- 4 Trombones

- Tuba

- Percussion

(Requires total of seven players)

- Timpani (2 players and 8 timpani, with a third player in the last movement using two of the second timpanist's drums)

- Several Snare Drums

- Bass Drum

- Cymbals

- Triangle

- Glockenspiel

- 3 deep, untuned steel rods or bells

- Rute, or "switch", to be played on the shell of the bass drum

- 2 Tam-tams (high and low)

- Offstage Percussion in Movement 5:

- Bass drum with cymbals attached (played by the same percussionist), Triangle, Timpano

- Voices

- Soprano Solo (used in fifth movement only)

- Alto Solo (sometimes credited as and sung by a mezzo-soprano) (used in fourth & fifth movements only)

- Mixed Chorus (used in fifth movement only)

- Strings

- Harps I, II (several to each part in the last movement and possibly at one point in the Scherzo)

"The largest possible contingent of strings"

- First and Second Violins

- Violas

- Violoncellos

- Double basses (some with low C extension).

Form

The work in its finished form has five movements:

- Allegro maestoso

- Musically, the first movement – written in C minor – though passing through a number of different moods, often resembles a funeral march, and is violent and angry.

- The form of this movement is somewhat similar to a Classical Sonata form. The exposition is repeated in a varied form (from rehearsal letter 4 through 15, as often does Beethoven in his Late Quartets. The development presents several ideas that will be used later in the symphony, including a theme based on the Dies Irae plainchant.

- Mahler uses a somewhat modified tonal framework for the movement. The secondary theme, first presented in E major (enharmony of Fb major, neapolitan of Mib), begins its second statement in C major, a key in which it is not expected until the recapitulation. The statement in the recapitulation, coincidentally, is in the original E major (Fb major). The eventual goal of the symphony, E-flat major, is briefly hinted at after rehearsal 17, with a theme in the trumpets that returns in the finale.

- Following this movement, Mahler calls in the score for a gap of five minutes before the second movement. This pause is rarely observed today. Often conductors will meet Mahler half way, pausing for a few minutes while the audience takes a breather and settles down and the orchestra retunes in preparation for the rest of the piece. Julius Buths received this instruction from Mahler personally, prior to a 1903 performance in Düsseldorf;[10] however, he chose instead to place the long pause between the fourth and fifth movements, for which Mahler congratulated him on his insight, sensitivity, and daring to go against his stated wishes.[11]

- Andante moderato

- The second movement is a delicate Ländler in A-flat major with two contrasting sections of slightly darker music. This slow movement itself is contrasting to the two adjacent movements. Structurally, it is one of the simplest movements in Mahler's whole output. It is the remembrance of the joyful times in the life of the deceased.

- In ruhig fließender Bewegung (With quietly flowing movement)

- The third movement is a scherzo in C minor. It opens with two strong, short timpani strokes. It is followed by two softer strokes, and then followed by even softer strokes that provide the tempo to this movement, which includes references to Jewish folk music. Mahler called the climax of the movement, which occurs near the end, sometimes a "cry of despair", and sometimes a "death-shriek". The movement is based on Mahler's setting of "Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt" from "Des Knaben Wunderhorn", which Mahler composed almost concurrently. (This movement was the basis for the third movement of Luciano Berio's "Sinfonia", where it is used as the framework for adding, collage-like, a great many quotations and references to other scores.)

- Urlicht (Primeval Light). Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht

- The fourth movement, Urlicht, is a Wunderhorn song, sung by an alto, which serves as an introduction to the Finale in a manner similar to the bass recitative in Beethoven's Ninth. The song, set in the remote key of D-flat major, illustrates the longing for relief from worldly woes, leading without a break to the response in the Finale.

- Im Tempo des Scherzos (In the tempo of the scherzo)

- The finale is the longest, typically lasting over half an hour. It is divided into two large parts, the second of which begins with the entry of the chorus and whose form is governed by the text of this movement. The first part is instrumental, and very episodic, containing a wide variety of moods, tempi and keys, with much of the material based on what has been heard in the previous movements, although it also loosely follows sonata principles. New themes introduced are used repeatedly and altered.

- The movement opens with a long introduction, beginning with the "cry of despair" that was the climax of the third movement, followed by the quiet presentation of a theme which re-appears as structural music in the choral section, and by a call in the offstage horns. The first theme group reiterates the "Dies Irae" theme from the first movement, and then introduces the "resurrection" theme to which the chorus will sing their first words, and finally a fanfare. The second theme is a long orchestral recitative, which provides the music for the alto solo in the choral section. The exposition concludes with a re-statement of the first theme group. This long opening section serves to introduce a number of themes, which will become important in the choral part of the finale.

- The development section is what Mahler calls the "march of the dead". It begins with two long drum rolls, which include the use of the gongs, In addition to developing the Dies Irae and resurrection themes and motives from the opening cry of despair, this section also states, episodically, a number of other themes, based on earlier material. The recapitulation overlaps with the march, and only brief statements of the first theme group are re-stated. The orchestral recitative is fully recapitulated, and is accompanied this time by offstage interruptions from a band of brass and percussion. This builds to a climax, which leads into a re-statement of the opening introductory section. The horn call is expanded into Mahler's "Great Summons", a transition into the choral section.

- Tonally, this first large part, the instrumental half of the movement, is organized in F minor. After the introduction, which recalls two keys from earlier movements, the first theme group is presented wholly in F minor, and the second theme group in the subdominant, B-flat minor. The re-statement of the first theme group occurs in the dominant, C major. The development explores a number of keys, including the mediant, A-flat major, and the parallel major, F major. Unlike the first movement, the second theme is recapitulated as expected in the tonic key. The re-statement of the introduction is thematically and tonally a transition to the second large part, moving from C-sharp minor to the parallel D-flat major — the dominant of F-sharp minor — in which the Great Summons is stated.. The Epiphany comes in, played by the flute, in a high register, and featuring trumpets, that play offstage. The choral section begins in G-flat major.

- The chorus comes in quietly a little past the halfway point of the movement. The choral section is organized primarily by the text, using musical material from earlier in the movement. (The B-flat below the bass clef occurs four times in the choral bass part: three at the chorus' hushed entrance and again on the words "Hör' auf zu beben". It is the lowest vocal note in standard classical repertoire. Mahler instructs basses incapable of singing the note remain silent rather than sing the note an octave higher.) Each of the first two verses is followed by an instrumental interlude; the alto and soprano solos, "O Glaube", based on the recitative melody, precede the fourth verse, sung by the chorus; and the fifth verse is a duet for the two soloists. The opening two verses are presented in G-flat major, the solos and the fourth verse in B-flat minor (the key in which the recitative was originally stated), and the duet in A-flat major. The goal of the symphony, E-flat major, the relative major of the opening C minor, is achieved when the chorus picks up the words from the duet, "Mit Flügeln", although after eight measures the music gravitates to G major (but never cadences on it).

- E-flat suddenly re-enters with the text "Sterben werd' ich um zu leben," and a proper cadence finally occurs on the downbeat of the final verse, with the entrance of the heretofore silent organ (marked "volles Werk") and with the choir instructed to sing "mit höchster Kraft" (with highest power). The instrumental coda is in this ultimate key as well, and is accompanied by the tolling of deep bells. Mahler went so far as to purchase actual church bells for performances, finding all other means of achieving this sound unsatisfactory. Mahler wrote of this movement: "The increasing tension, working up to the final climax, is so tremendous that I don’t know myself, now that it is over, how I ever came to write it." [12]

Text

Note: This text has been translated from the original German text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn to English on a very literal and line-for-line basis, without regard for the preservation of meter or rhyming patterns.

Fourth Movement

- Original German

- Urlicht

- O Röschen rot!

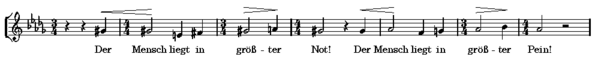

- Der Mensch liegt in größter Not!

- Der Mensch liegt in größter Pein!

- Je lieber möcht' ich im Himmel sein.

- Da kam ich auf einen breiten Weg:

- Da kam ein Engelein und wollt’ mich abweisen.

- Ach nein! Ich ließ mich nicht abweisen!

- Ich bin von Gott und will wieder zu Gott!

- Der liebe Gott wird mir ein Lichtchen geben,

- Wird leuchten mir bis in das ewig selig Leben!

- In English

- Primeval Light

- O red rose!

- Man lies in greatest need!

- Man lies in greatest pain!

- How I would rather be in heaven.

- There came I upon a broad path

- when came a little angel and wanted to turn me away.

- Ah no! I would not let myself be turned away!

- I am from God and shall return to God!

- The loving God will grant me a little light,

- Which will light me into that eternal blissful life!

Fifth Movement

Note: The first eight lines were taken from the poem Die Auferstehung by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock.[13] Mahler omitted the final four lines of this poem and wrote the rest himself (beginning at "O glaube").

- Original German

- Aufersteh'n, ja aufersteh'n

- Wirst du, Mein Staub,

- Nach kurzer Ruh'!

- Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben

- wird der dich rief dir geben!

- Wieder aufzublüh'n wirst du gesät!

- Der Herr der Ernte geht

- und sammelt Garben

- uns ein, die starben!

- O glaube, mein Herz, o glaube:

- Es geht dir nichts verloren!

- Dein ist, ja dein, was du gesehnt!

- Dein, was du geliebt,

- Was du gestritten!

- O glaube

- Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren!

- Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!

- Was entstanden ist

- Das muß vergehen!

- Was vergangen, auferstehen!

- Hör' auf zu beben!

- Bereite dich zu leben!

- O Schmerz! Du Alldurchdringer!

- Dir bin ich entrungen!

- O Tod! Du Allbezwinger!

- Nun bist du bezwungen!

- Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen,

- In heißem Liebesstreben,

- Werd'ich entschweben

- Zum Licht, zu dem kein Aug' gedrungen!

- Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen

- Werde ich entschweben.

- Sterben werd' ich, um zu leben!

- Aufersteh'n, ja aufersteh'n

- wirst du, mein Herz, in einem Nu!

- Was du geschlagen

- zu Gott wird es dich tragen!

- In English

- Rise again, yes, rise again,

- Will you My dust,

- After a brief rest!

- Immortal life! Immortal life

- Will He who called you, give you.

- To bloom again were you sown!

- The Lord of the harvest goes

- And gathers in, like sheaves,

- Us together, who died.

- O believe, my heart, O believe:

- Nothing to you is lost!

- Yours is, yes yours, is what you desired

- Yours, what you have loved

- What you have fought for!

- O believe,

- You were not born for nothing!

- Have not for nothing, lived, suffered!

- What was created

- Must perish,

- What perished, rise again!

- Cease from trembling!

- Prepare yourself to live!

- O Pain, You piercer of all things,

- From you, I have been wrested!

- O Death, You masterer of all things,

- Now, are you conquered!

- With wings which I have won for myself,

- In love’s fierce striving,

- I shall soar upwards

- To the light which no eye has penetrated!

- Its wing that I won is expanded,

- and I fly up.

- Die shall I in order to live.

- Rise again, yes, rise again,

- Will you, my heart, in an instant!

- That for which you suffered,

- To God will it lead you!

Tonality

The symphony's first movement is in C minor, and the finale concludes in E♭ major, the relative major of C minor. Thus, the work exhibits progressive tonality; as a result, a titular description in terms of a single key is not realistic, and is not found in serious works of reference.

The symphony is sometimes described as being in the key of C minor; the 'New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians', however, represents the progressive tonal scheme by labelling the work's tonality as 'c--E♭' [14]

Premieres

- World premiere (first three movements only): March 4, 1895, Berlin, with the composer conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

- World premiere (complete): December 13, 1895, Berlin, conducted by the composer.

- Dutch premiere: October 26, 1904, Amsterdam, with the composer conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

- American premiere: December 8, 1908, New York City, conducted by the composer with the New York Symphony Orchestra.

- Recording premiere: 1924, Oskar Fried conducting the Berlin State Opera Orchestra.

- British premiere: April 16, 1931, London, conducted by Bruno Walter.

External links

- Symphony No. 2: Free scores at the International Music Score Library Project.

- History and analysis by renowned Mahler scholar Henry Louis de La Grange[dead link]

- The Music of Gustav Mahler: a catalogue of manuscript and printed sources The entry for the Second Symphony outlines the work's history, provides a list of performances up to 1911, a discography of early recordings, and detailed descriptions of the surviving manuscript and printed sources.

- Analysis by Parks Grant

- Classical Notes

Sources

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995). ISBN 0-19-506177-2.

References

- ^ a b Steinberg, 285.

- ^ Steinberg, 290-291.

- ^ Steinberg, 291.

- ^ "Symphony No. 2 in C minor (Resurrection)". Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/?fuseaction=composition&composition_id=2484. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Press review for World Premiere performance of the new Critical Edition of Mahler's Resurrection symphony

- ^ According to the instrumentation list in the edition of the Symphony published by Dover, both E-flat clarinets are doubled in ff where possible, but there is no indication of this in the score itself.

- ^ At no point does the score require two contrabassoons. In the first four movements, the third bassoon alternates on the contrabassoon, and in the fifth movement a fourth bassoon is added to the ensemble, which is assigned the doubling of the contrabassoon (presumably for convenience of writing the score).

- ^ At rehearsal number 3 in the fifth movement, "as many as possible, at great distance". Horn 7-10 return to the orchestra after number 31. (and start playing after no. 46)

- ^ At one point in the fifth movement, rehearsal numbers 22-25, there are two off-stage trumpet parts in F and C with multiple instruments on each part, according to the score playing from as furthest a distance as possible, which utilize players other than parts 1-6 of the orchestra. Later, four trumpet parts are used off-stage, which the score states are played by parts 3-6. In this passage, the score states that the four trumpets must play from opposite sides: the horns and offstage trumpets 2 and 4 on the left side and parts 1 and 3 on the right. For the final minutes of the symphony, the on-stage trumpets are to be joined with "reinforcement" players, presumably using the off-stage musicians from the section starting at rehearsal number 22. The figure of 8 total players assumes that in this passage only one trumpeter is playing on each of the two offstage parts, while the high-end figure of 10 assumes 2 on each part. It is probable, however, that Mahler would have preferred even more players in this section than allowed by the "ten" he indicated in the score, especially as he wrote "mehrfach besetz" rather "doppelt besezt" for the passages at rehearsal numbers 22-25 (that is "multiple to the part" rather than simply "doubled"), and as the indication for "reinforcement" applies to all six trumpet parts.

- ^ San Francisco Symphony

- ^ Kennedy Center

- ^ Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Recollections of Gustav Mahler, trans. Dika Newlin, ed. Peter Franklin (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980), pp. 43-44.

- ^ Klopstock's Die Auferstehung is not, as is commonly believed, one of his Oden, but rather from a set entitled Geistliche Lieder (Spiritual Songs).

- ^ 'Gustav Mahler', in New Grove, Macmillan, 1980

Symphonies by Gustav Mahler List of compositions by Gustav MahlerNo. 1 in D major ('Titan') · No. 2 ('Resurrection') · No. 3 · No. 4 · No. 5 · No. 6 in A minor ('Tragic') · No. 7 · No. 8 in E flat major ('Symphony of a Thousand') · Das Lied von der Erde · No. 9 · No. 10 (unfinished)

Categories:- Choral symphonies

- Symphonies by Gustav Mahler

- Music for orchestra and organ

- 1894 compositions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.