- Narva Offensive (18–24 March 1944)

-

This is a sub-article to Battle of Narva.

Narva Offensive (18–24 March 1944) Part of Eastern Front (World War II)

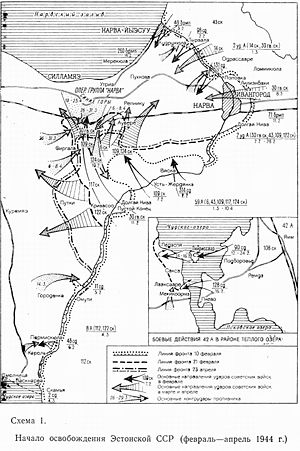

Soviet map of the beginning of the Estonian Operation (February – April 1944)Date 18–24 March 1944 Location Narva, Estonia Result German defensive victory Belligerents  Germany

Germany Soviet Union

Soviet UnionCommanders and leaders  Karl von Oven

Karl von Oven Ivan Korovnikov

Ivan KorovnikovStrength 1 infantry division,

some artillery, armoured vehicles

and aircraft6 rifle divisions

2500 artillery

100 armoured vehicles[1]

800 aircraft[2]Casualties and losses 38 armoured vehicles

21 artillery pieces[3]Leningrad and the Baltics 1941–1944June in Lithuania – Summer in Estonia – Evacuation of Tallinn – Nazi occupation – Toropets-Kholm – Demyansk – Sinyavino – Iskra – Polyarnaya Zvezda – Relief of the siege – Narva – Karelian isthmus – Vilnius – Kaunas – Southern Estonia – Riga – Northern Estonia – Attempt to restore independence of Estonia – Moonsund – Re-occupation of Estonia – Courland – Re-occupation of LatviaFormation of Narva bridgeheads – Narva (15–28 February) – Narva (1–4 March) – Bombing of Tallinn – Narva (18–24 March) – Narva (March–June) – Auvere – Narva (July) – Sinimäed – South Estonia – North Estonia – Porkuni – Moonsund Archipelago – TehumardiThe Narva Offensive (18–24 March 1944)[4] was a campaign fought between the German XXXXIII Army Corps and the Soviet 59th Army for the Narva Isthmus. At the time of the operation, Joseph Stalin was personally interested in taking Estonia, viewing it as a precondition for forcing Finland out of the war. The Soviet tank assault at Auvere railway station was stopped by the 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion. Fierce fighting continued for another week, when Soviet forces had suffered many casualties and switched over to the defensive.

Contents

Background

Further information: Narva Offensive (15–28 February 1944) and Narva Offensive (1–4 March 1944)The defeat in the preceding Narva offensive came as an unpleasant surprise to the leadership of the Leningrad Front, blaming it on the arrival of the freshly conscripted 20th Estonian SS Volunteer Division who were motivated to resist the looming Soviet re-occupation.[5] Since the beginning of January, the Leningrad Front had lost 227,440 troops killed, wounded, or missing, which constituted more than half of the men who participated in the Leningrad-Novgorod Strategic Offensive. Both sides rushed in reinforcements.[6][7] The 59th Army was brought to Narva and the 8th Estonian Rifle Corps was placed under the command of the Leningrad Front. After this deployment, the Narva sector acquired the highest concentration of forces on the Eastern Front in March 1944.[6]

Preceding combat

The newly arrived 59th Army attacked westwards from the Krivasoo bridgehead south of the city of Narva and encircled the strongpoints of the 214th Infantry Division and two Estonian Eastern Battalions. The resistance of the encircled units gave the German command enough time to move in a platoon from the SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 23 "Norge" and to stop the units of the 59th Army.

Design

The objective of the Soviet offensive was the headquarters of the XXXXIII Army Corps on the Lastekodumägi height in the Sinimäed Hills next to the highway between Narva–Tallinn, sixteen kilometres west of Narva. The defence was built up as an array of posts between the hills and the railway.

Deployments

German

- 61st Infantry Division - General Günther Krappe

- Artillery Command No. 113

- Tank squadron of the 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion - Lieutenant Otto Carius

Soviet

- 6th Rifle Corps - Major General Semyon Mikulski

- 3 divisions

- 109th Rifle Corps - Major General Ivan Alferov

- 3 divisions

- 46th, 260th and 261st Separate Guards Heavy Tank and 1902nd Self-propelled Artillery regiments[8]

- 3rd Breakthrough Artillery Corps - Major General N. N. Zhdanov

- 3rd Guards Tank Corps - Major General I. A. Vovchenko

Combat activity

The six Soviet divisions, armoured vehicles and artillery of the 109th Rifle Corps and the newly arrived 6th Rifle Corps attacked the weakened 61st Infantry Division at the defence of Auvere station. The 162nd Grenadier Regiment was shaken by the massive preparatory artillery bombardment and air attack. The Soviet 930th Regiment broke through the thinned-out defence line of the 61st Infantry Division through to the railway, pushing towards the headquarters of the XXXXIII Army Corps.[9] Six Soviet T-34 tanks were destroyed by the two Tger tanks of Lieutenant Otto Carius, forcing the Soviet infantry to withdraw.[10][11]

Casualties

The German side claimed that on 17–22 March, their 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion destroyed 38 tanks, four self-propelled guns and 17 assault guns.[3][11]

Aftermath

Main article: Battle of Narva (1944)Brigadeführer Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz von Gross-Zauche und Camminetz's kampfgruppe annihilated the Soviet 59th Army shock troop wedge at the western end of the Krivasoo Bridgehead on 26 March. The kampfgruppe destroyed the eastern tip of the Soviet bridgehead on 6 April. Strachwitz, inspired by this success, tried to eliminate the whole bridgehead, but was unable to proceed due to the spring thaw that had rendered the swamp impassable for his tanks.[10] By the end of April, the parties had mutually exhausted their strengths. Relative calm settled on the front until late July, 1944.[2][7]

References

- ^ F.I.Paulman (1980). "Nachalo osvobozhdeniya Sovetskoy Estoniy" (in Russian). Ot Narvy do Syrve (From Narva to Sõrve). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat. pp. 7–119.

- ^ a b Toomas Hiio (2006). "Combat in Estonia in 1944". In Toomas Hiio, Meelis Maripuu, & Indrek Paavle. Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1035–1094.

- ^ a b Wilhelm Tieke (2001). Tragedy of the faithful: a history of the III. (germanisches) SS-Panzer-Korps. Winnipeg: J.J.Fedorowicz.

- ^ David M. Glantz (2001). The Soviet-German War 1941-1945: Myths and Realities. Glemson, South Carolina: Strom Thurmond Institute of Government and Public Affairs, Clemson University. http://www.strom.clemson.edu/publications/sg-war41-45.pdf.

- ^ V. Rodin (October 5, 2005) (in Russian)). Na vysotah Sinimyae: kak eto bylo na samom dele. (On the Heights of Sinimäed: How It Actually Was. Vesti.

- ^ a b L. Lentsman (1977) (in Estonian). Eesti rahvas Suures Isamaasõjas (Estonian Nation in Great Patriotic War). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- ^ a b Laar, Mart (2005). "Battles in Estonia in 1944". Estonia in World War II. Tallinn: Grenader. pp. 32–59.

- ^ Операция "Нева-2" http://www.rkka.ru/memory/baranov/6.htm chapter 6, Baranov, V.I., Armour and people, from a collection "Tankers in the combat for Leningrad"Lenizdat, 1987 (Баранов Виктор Ильич, Броня и люди, из сборника "Танкисты в сражении за Ленинград". Лениздат, 1987)

- ^ Евгений Кривошеев; Николай Костин (1984). "I. Sraženie dlinoj v polgoda (Half a year of combat)" (in Russian). Битва за Нарву, февраль-сентябрь 1944 год (The Battle for Narva, February–September 1944). Tallinn: Eesti raamat. pp. 9–87.

- ^ a b Otto Carius (2004). Tigers in the Mud: The Combat Career of German Panzer Commander Otto Carius. Stackpole Books.

- ^ a b Mart Laar (2006) (in Estonian). Sinimäed 1944: II maailmasõja lahingud Kirde-Eestis (Sinimäed Hills 1944: Battles of World War II in Northeast Estonia). Tallinn: Varrak.

Categories:- Battle of Narva

- Battles involving Estonia

- 1944 in Estonia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.