- Mosul Vilayet

-

ولايت موصل

Vilâyet-i MusulVilayet of the Ottoman Empire ←

1878–1918  →

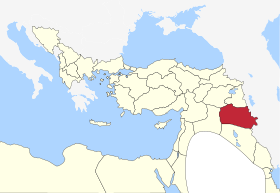

→Mosul Vilayet in 1900 Capital Mosul[1] History - Established 1878 - Armistice of Mudros 1918 Today part of  Iraq

IraqThe Vilayet of Mosul[1] (Ottoman Turkish: ولايت موصل, Vilâyet-i Musul) was a vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. It was created from the northern sanjaks of the Vilayet of Baghdad in 1878.[2]

At the beginning of the 20th century it reportedly had an area of 29,220 square miles (75,700 km2), while the preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population as 300,280.[3] It should be noted that the accuracy of the population figures ranges from "approximate" to "merely conjectural" depending on the region from which they were gathered.[3]

Contents

Administrative divisions

Sanjaks of the Vilayet:[4]

- Sanjak of Mosul

- Sanjak of Kerkük (Sehr-i-Zor)

- Sanjak of Süleymaniye

Mosul question

The Vilayet Mosul had a Kurdish speaking population and an Arabic speaking population, and in contrast to Mosul’s neighbors, it was much more directly integrated into the Ottoman Empire.[5] With regards to the religious communities, it was predominately Sunni with notable communities of Turkmen, Kurds, Jews and Christians with a total population of about 800,000 people in the early 1900s.[6] These communities and their respective leaders were heavily influenced by the political hierarchy, trading networks, and the judicial system of the Ottoman Empire, even though they considered themselves on their own and not completely controlled by the empire.[5] During the period of Ottoman rule, Mosul was involved in the production of fine cotton goods. Oil was a known commodity in the region and it became critically important during WWI and continuing until today. Mosul was considered a trading capital of the Ottoman Empire because of its location along the trade routes to India and the Mediterranean; also it was considered a political sub-capitol. However there were many issues in the Vilayet during the Ottoman period. The leadership was constantly plagued with accusations of corruption and incompetence, and leaders were replaced with an alarming regularity.[7] Also, because of these problems, the administration of Mosul was entrusted to Palace and notable favorites, where the high official’s careers were usually determined by tribal issues within their states.[7]

Turkey

Near the end of World War I, the debilitated Ottoman Empire signed an armistice with the British called the Armistice of Mudros and it was signed on October 30, 1918. This armistice called for a ceasing of all fighting between the British and the Ottomans. Three days later, on November 2, Sir William Marshall, a British Lieutenant General, invaded the Mosul Vilayet until November 15, 1918 when he is finally successful in defeating the Ottoman forces and causing them to surrender.[8] In August 1920, the Treaty of Sèvres was signed to end the war, however the Ottomans still contested the British right to Mosul and how it was taken illegally, post-Mudros. Even when the Lausanne Treaty was signed between Turkey and Britain in 1923, Turkey still maintained that Britain was controlling the Mosul Vilayet illegally.[9] British officials in London and Baghdad continued to believe that Mosul was imperative to the survival of Iraq because of its resources and the security of its mountainous border.[10] Turkish leaders were also afraid that Kurdish nationalism would thrive under British Mandate and start trouble with the Kurdish population in Turkey.[6] In order to reach a resolution on the conflicting claims over Mosul, the League of Nations was called on to send a fact-finding commission in order to determine the rightful owner. The commission investigated the region and then reported that Turkey had no claim to Mosul and it belonged to the British and no one else had any rightful claim to the area.[9] Because of the amount of influence wielded by Britain in the League of Nations, the decision of the fact-finding commission was not surprising.[citation needed] Another aspect Britain’s influence on the League of Nations was that the Secretary of the War Cabinet, Maurice Hankey, decided that Britain needed to have control over the whole area because of their oil concerns for the Royal Navy before the commission was completed.[8] Another area of contention between Britain and Turkey was the actual boundary line. There was a Brussels Line which had been decided by the League of Nations as the true border of Iraq, and a British line which was the division line the Britain had used as reference in the past. When this was brought up to British leaders, both Percy Cox, the British High Commissioner of Iraq, and Arnold Wilson, the British civil commissioner in Baghdad, urged Lloyd George, who was the Prime Minister, to use the Brussels line because they did not think there was that large of a difference between the two line boundaries.[11]

The Mosul Vilayet was not just contested by external powers, i.e. Britain and Turkey; Faysal ibn Husayn, the Hashemite ruler who had become the king of the newly created state of Iraq by the British in 1921, also wanted to claim the Mosul Vilayet as his. The British liked, and respected Faysal because of all of the assistance he had given to them; the British also felt that they could trust him to do what they wanted. In this belief, Britain was both right and wrong. Faysal was a brilliant diplomat who was able to balance what the British wanted and the true needs of his people into a very complex system. However, one of the things he wanted most was the unification and strong status of Iraq and he did not believe that was possible without having control of the Mosul Vilayet. Prior to the League of Nations decision, Faysal had continually petitioned the British government to give control of Mosul to him so that he could succeed in his aim of unification. Finally, after the League of Nations decision, the British agree to let Faysal have control over Mosul in return for important resource concessions. The British founded the Turkish Petroleum Company which they later named the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC). Because Britain also wanted to soothe Turkish anger over the League of Nations decision, they gave them a portion of the oil profits. By having control over the oil and the IPC, the British stayed in control of the resources of Mosul even though they had given political control back to Faysal.

The Kurds

Another internal group that wanted control over Mosul was the Kurds. The Kurds were the natural inhabitants of some parts of the Vilayet and didn’t want to belong to any other government other than their own. They had long fought against being integrated into Iraq because they wanted independence. Most Kurds did not consider themselves as a part of the new country of Iraq. Various Kurdish leaders rallied Kurdish groups who already had their own firepower and had been helped by different imperial powers on occasions when it suited their needs. Furthermore, many Kurds felt betrayed by promises the British had made to them in earlier times and subsequently not kept. Faysal wanted to integrate them because, as nearly exclusively Sunnis, he needed them to balance out the Shiite population. Britain used both the Kurdish firepower and Faysal’s desire for a united Iraq in order to keep a stranglehold over him, and later Iran used the Kurds and their firepower in order to keep unrest in Iraq during the reign of Khomeini. The Kurds did not want to be integrated into Iraq; however they did support the continuance of the British mandate in the area.[6]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Geographical Dictionary of the World at Google Books

- ^

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Bagdad, Turkey (Vilayet)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Bagdad,_Turkey_%28Vilayet%29.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Bagdad, Turkey (Vilayet)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Bagdad,_Turkey_%28Vilayet%29. - ^ a b Asia by A. H. Keane, page 460

- ^ Musul Vilayeti | Tarih ve Medeniyet

- ^ a b "A History of Iraq" by Charles Tripp, New York: Cambridge Press 2007[page needed]

- ^ a b c The Mosul Dispute "The American Journal of International Law" by Quincy Wright[page needed]

- ^ a b "Ottoman Administration of Iraq 1890-1908" by Gokhan Cetinsaya New York: Routledge, 2006[page needed]

- ^ a b Mesopotamia in British War Aims "The Historical Journal" by V.H. Rothwell[page needed]

- ^ a b The Geography of the Mosul Boundary "The Geographic Journal" by H.I. Lloyd 1926[page needed]

- ^ "The Creation of Iraq: 1914-1921" by Reeva Spector Simon and Eleanor H. Tejirian, New York: Columbia University Press 2004[page needed]

- ^ The Geography of the Mosul Boundary: Discussion "The Geographical Journal" 1926[page needed]

Subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire

Subdivisions of the Ottoman EmpireEyalets (1363–1864) AfricaAnatoliaAdana · Aidin · Anatolia · Ankara · Archipelago · Diyarbekir · Dulkadir · Erzurum · Hüdavendigâr · Karaman · Karasi · Kars · Kastamonu · Rum · Trebizond · VanAsiaEuropeVilayets (1864–1922) AnatoliaAdana · Aidin · Ankara · Archipelago · Bitlis · Diyâr-ı Bekr · Erzurum · Hüdavendigâr · Istanbul · Kastamonu · Konya · Mamuret-ul-Aziz · Sivas · Trebizond · VanEuropeElsewhereVassals and autonomies Cossack Hetmanate · Cretan State · Crimean Khanate · Khedivate of Egypt · Principality of Moldavia · Sharifate of Mecca · Republic of Ragusa · Eastern Rumelia · Principality of Samos · Serbian Despotate · Duchy of Syrmia · Principality of Transylvania · Tunis Eyalet · Principality of WallachiaSee also the list of short-lived Ottoman provinces Categories:- States and territories established in 1878

- States and territories disestablished in 1918

- Vilayets of the Ottoman Empire in Asia

- States and territories established in 1879

- Ottoman Iraq

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.