- Mythology of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples

-

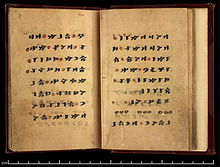

The 10th-century Irk Bitig or "Book of Divination" of Dunhuang is an important source for early Turkic mythology

The 10th-century Irk Bitig or "Book of Divination" of Dunhuang is an important source for early Turkic mythology

The mythologies of the Turkic and Mongol peoples are related and have exerted strong influence on one another. Both groups of peoples qualify as Eurasian nomads and have been in close contact throughout history, especially in the context of the medieval Turco-Mongol empire.

The oldest mythological concept that can be reconstructed with any certainty is the sky god Tengri, attested from the Xiong Nu in the 2nd century BC.

Geser (Ges'r, Kesar) is a Mongol religious epic about Geser (also known as Bukhe Beligte), prophet of Tengriism.

Among the oldest sources for Turkic religion and mythology are the Irk Bitig, a 10th-century manuscript found in Dunhuang, and the historian Movses Kaghankatvatsi describing the Huns of the Caucasus, also of the 10th century. besides epigraphic evidence of the Orkhon inscriptions of Mongolia and the Greek inscriptions of Madara.

Contents

Mongol

Bai-Ulgan and Esege Malan are creator deities. Ot is the goddess of marriage. Tung-ak is the patron god of tribal chiefs. The Uliger are traditional epic tales and the Epic of King Gesar is shared with much of Central Asia and Tibet. Erlig Khan (Erlik Khan) is the King of the Underworld. Daichin Tengri is the red god of war to whom enemy soldiers were sometimes sacrificed during battle campaigns. Zaarin Tengri is a spirit who gives Khorchi (in the Secret History of the Mongols) a vision of a cow mooing "Heaven and earth have agreed to make Temujin (later Genghis Khan) the lord of the nation". The wolf, falcon, deer and horse were important symbolic animals.

There are many different Mongol creation myths. In one, the creation of the world is attributed to a Lama. In the beginning there was only water, and from the heavens Lama came down to it holding an iron rod from which he began to stir the water. The stirring brought about a wind and fire which caused a thickening at the center of the waters to form earth.[1] Another narrative also attributes the creation of heaven and earth to a lama who is called Udan. Udan began by separating earth from heaven, and then dividing heaven and earth both into nine stories, and creating nine rivers. After the creation of the earth itself, the first male and female couple were created out of clay. They would become the progenitors of all humanity.[2]

In another example the world began as an agitating gas which grew increasingly warm and damp, precipitating a heavy rain that created the oceans. Dust and sand emerged to the surface and became earth.[2] Yet another account tells of the Buddha Sakyamuni searching the surface of the sea for a means to create the earth and spotted a golden frog. From its east side, Buddha pierced the frog through, causing it to spin and face north. From its mouth burst fire and from its rump streamed water. Buddha tossed golden sand on his back which became land. And this was the origin of the five earthly elements, wood and metal from the arrow, and fire, water and sand.[2] These myths date from the 17th century when Yellow Shamanism (Tibetan Buddhism using shamanistic forms) was established in Mongolia. Black Shamanism and White Shamanism from pre-Buddhist times survives only in far-northern Mongolia (around Lake Khuvsgul) and the region around Lake Baikal where Lamaist persecution had not been effective.

Turkic

The Wolf (Böri) symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Asena (Ashina Tuwu) is the wolf mother of Bumen, the first Khan of the Göktürks.

The Horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology; Turks considered the horse an extension of the individual -though generally dedicated to the male- and see that one is complete with it. This might have led to or sourced from the term "At-Beyi" (Horse-Lord).

The Dragon (Evren), also expressed as a Snake or Lizard, is the symbol of might and power. It is believed, especially in mountainous Central Asia, that dragons still live in the mountains of Tian Shan/Tengri Tagh and Altay. Dragons also symbolize the god Tengri (Tanrı) in ancient Turkic tradition, although dragons themselves are not worshipped as gods.

The legend of Timur (Temir) is the most ancient and well-known. Timur found a strange stone that fell from the sky (an iron ore meteorite), making the first iron sword from it.[citation needed] Today, the word "demir" means "iron".

Turkic mythology was influenced by other local mythologies. For example, in Tatar mythology elements of Finnic and Indo-European myth co-exist. Subjects from Tatar mythology include Äbädä, Şüräle, Şekä, Pitsen, Tulpar, and Zilant.

The legend of Oghuz Khan is a central political mythology for Turkic peoples of Central Asia and eventually the Oghuz Turks who ruled in Anatolia. Versions of this narrative have been found in the histories of Rashid ad-Din Tabib, in an anonymous 14th c? Uyghur vertical script manuscript now in Paris, and in Abu'l Ghazi's Shajara at-Turk and have been translated into Russian and German.

See also

- Alpamysh

- Turco-Mongol

- Asena

- Finno-Ugric mythology

- Tibetan mythology

- Scythian mythology

- Shamanism in Siberia

- Epic of Manas

- The Secret History of the Mongols

- Turkish folklore

- Korean mythology

- Burkhanism

Notes

- ^ Sproul 1979, p. 218

- ^ a b c Nassen-Bayer & Stuart 1992

References

- Walter Heissig, The Religions of Mongolia, Kegan Paul (2000).

- Gerald Hausman , Loretta Hausman, The Mythology of Horses: Horse Legend and Lore Throughout the Ages (2003), 37-46.

- Yves Bonnefoy, Wendy Doniger, Asian Mythologies, University Of Chicago Press (1993), 315-339.

- 满都呼, 中国阿尔泰语系诸民族神话故事(folklores of Chinese Altaic races).民族出版社, 1997. ISBN 7105026987.

- 贺灵, 新疆宗教古籍资料辑注(materials of old texts of Xinjiang religions).新疆人民出版社, May 2006. ISBN 722810346.

- Nassen-Bayer; Stuart, Kevin (1992-10). Mongol creation stories: man, Mongol tribes, the natural world and Mongol deities. 2. 51. Asian Folklore Studies. pp. 323–334. http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-EPT/stuart1.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- Sproul, Barbara C. (1979). Primal Myths. HarperOne HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 9780060675011.

- S. G. Klyashtornyj, 'Political Background of the Old Turkic Religion' in: Oelschlägel, Nentwig, Taube (eds.), "Roter Altai, gib dein Echo!" (FS Taube), Leipzig, 2005, ISBN 9783865830623, 260-265.

External links

Categories:- Mongol mythology

- Turkic mythology

- Creation myths

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.