- The Meermin slave mutiny

-

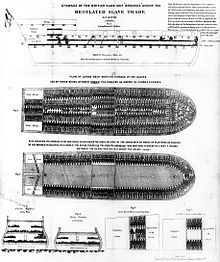

The Meermin was a ship of this typeCareer (Netherlands) Dutch East India Company Name: Meermin Owner: Dutch East India Company Launched: 1759 Out of service: 1766 Fate: beached General characteristics Class and type: hoeker Tons burthen: 480[1] The Mutiny on the slave ship Meermin took place in February 1766. The Meermin, a 480-ton three-masted[1] and square-rigged ship, built in 1759 in Amsterdam[2] was one of many slave ships owned by the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

The final voyage of the Meermin ended with a dramatic slave mutiny that resulted in deaths of half the crew and nearly 30 of the slaves.[3] The decision was made to release slaves from their shackles, to avoid loss through death and disease in the overcrowded conditions and to work with and entertain the crew. In mid-February supercargo Johan Krause gave the slaves weapons to clean, and the slaves seized both the opportunity and the ship.

A truce was arranged with the slaves demanding their return to Madagascar in return for preserving the lives of the rest of the crew. The crew, however, deceived the slaves and sailed instead for the South African coast. Landfall was finally made at the Dutch settlement of Struisbaai where the final confrontation between slaves and a militia of farmers formed by a local magistrate took place.

The last remaining members of the crew on board ship, under the leadership of Olaf Leij, managed to communicate with the onshore militia by means of messages in bottles in the final deception which was to end the three-week-long mutiny. Captain Muller and the slave leader Massavana were tried in the VOC Court after the event. Muller was stripped of his position, rank and wages; Massavana was sentenced to remain on Robben Island, and died there three years later.

Contents

Voyage

From the mid-seventeenth to mid-nineteenth centuries the Dutch East India Company (VOC) transported approximately 63,000 slaves into the Cape colony, and millions to the Americas.[4] The Meermin was working the coastline of South Africa and Madagascar from December to February 1765, under Captain Gerrit Muller and a crew of 56, collecting slaves – men, women and children – for the Cape of Good Hope. She set sail from Madagascar on 20 January 1766 carrying 140 slaves.[2][5]

Mutiny

Supercargo Johan Krause, an experienced shipmaster, believed himself to be intellectually superior to the slaves of whom he was in charge. To avoid the loss of profit of slaves dying while at sea Krause convinced Muller (not only in his first command,[4] but now also unwell)[3] to unshackle them and let them work on deck.[4] The slaves were released from their chains once the ship was under sail; the men assisted the crew, and the women provided entertainment with dancing and singing. Between 16 February[2] and 18 February[6] Krause took the unwise decision to order the slaves to "clean some assegais"[7] and guns. Muller agreed, but once the slaves had the weapons they turned on the ship's crew, under the de facto leadership of a man named Massavana. Muller was injured, and Krause was killed together with twenty-three of the crew; the bodies were thrown into the sea. Krause's assistant Olaf Leij was left in charge of the remaining crew,[4] some of whom hid in a locker room close to the rudder. Those on the decks retreated by climbing the foremast, where they threatened to use hand grenades stored there in order to keep the slaves back.[2]

Truces and betrayal

With the crew held captive, the slaves did not know how to control the ship, so she drifted for three days while this impasse lasted. The members of the crew on the foremast reached an agreement with the slaves: the crew's lives were to be spared on condition that they sailed the Meermin back to Madagascar. The truce broke down, and the crew members who had retreated to the foremast were also killed and thrown overboard.[2]

The third element of the crew were those who had hidden in the locker room close to the rudder. On the third day they managed to cause a small explosion with gunpowder to which they had access. A further truce was made when a female slave was brought into negotiations,[8] and asked to tell the other slaves that if they did not surrender the crew would blow up the ship. Again, the slaves imposed the condition that the Meermin be sailed back to Madagascar. However, the crew steered the ship slowly in the direction of Madagascar during daylight, but each night set full sail southwards towards Cape Agulhas.[2] The slaves were unaware of the deception.[9] After three[2] or four[6] days' sailing, land was sighted; the crew had managed to steer the Meermin towards the Dutch settlement of Struisbaai.[4] Olaf Leij, who spoke a little of the Malagasy language, assured the slaves that this was the Madagascan coast.[10] The anchor was dropped while the ship was some kilometres from the shore, and over fifty[6] – perhaps seventy[9] – of the slaves, men and women, set off for the shore in the longboat and pinnace.[2] They had promised their fellow slaves that they would light signal fires on the beach, and send the boats back, if it was safe for the remaining slaves to follow.[11]

On landing, the slaves caught sight of Matthys Rodstock's farm[6] and discovered the deception practised on them by the ship's crew. Local magistrate Johannes La Sueur rallied local farmers into an impromptu militia to capture the slaves.[4] There was no surrender; fourteen slaves were shot dead and the rest imprisoned.[6]

Final stages

Extract from messageAlthough we trust in the Lord to save us we kindly request the finder of this letter to light three fires on the beach and stand guard at these behind the dunes, should the ship run aground, so that the slaves may not become aware that this is a Christian country. They will certainly kill us if they establish that we made them believe that this is their country.

“”The approximately ninety slaves remaining on the ship throughout the following week lost patience waiting for the promised signal fires and boats. The surviving crew members noticed that the current was setting onshore, and knowing the arrangements for signal fires, wrote messages asking for the Dutchmen on land to light three fires on the shore. These messages were sealed into bottles and set adrift in the onshore current. Two of those bottles were successfully retrieved, delivered to Johannes La Sueur on 6 March,[9] and the fires were lit.[6] One of these messages is preserved in the Cape Archives Repository.[10][12] The slaves on the ship, seeing the signal fires, cut the anchor cable to allow the Meermin to drift shorewards. They then lowered a canoe in which six of them set out for the shore, only to be immediately surrounded. Five of the six were imprisoned, the other shot. The slaves on the ship, enraged at the crew for their deception, attacked them – but this time the crew were able to defend themselves for as long as it took for the Meermin to run aground. This battle lasted for three hours. Both sides became exhausted, and eventually Olaf Leij persuaded the remaining slaves to surrender by promising them that if they allowed themselves to be chained again, they would not be punished. The last of the slaves surrendered. Of the 140 slaves which had been shipped, 112 reached the Cape.[10][12]

Aftermath

For the next week, the Dutch authorities salvaged as much as possible from the Meermin. Nearly 300 firearms were recovered, together with gunpowder and musket balls, compasses, and five bayonets. Cables, ropes and other items from the ship were auctioned on the shore. The Meermin broke up where she grounded.[9]

Rulings in the VOC Court of Justice were one of the biggest steps of recognition that oppressed people, including slaves, were capable of free thought.[4] The Captain of the ship was found guilty of culpable negligence, stripped of his rank, docked of his pay, and dismissed from the company.[10][12] He was also banned from the Cape, and had to work his passage home to Amsterdam. The slave leader, Massavana, was also put on trial, and for lack of sufficient evidence was not executed. He was instead sentenced to be “put on the island until further instructions.” Massavena survived on Robben Island until 20 December 1769.[8]

Archaeology

On Heritage Day 1998, the South African Cultural History Museum, which was located in what had, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, been the accommodation for government-owned slaves,[13][14] was renamed the Old Slave Lodge, and money was obtained for a maritime archaeology project to find and salvage the wreck of the Meermin, with the commissioning of historical and archaeological research on the episode following the publication of The Mutiny on the Meermin.[15]

Iron fastenings were used extensively in wooden ships. This combined with the possible presence of anchors and cannon give fairly good signatures.

“”The South African lottery board released funds for archeological research by Jaco Boshoff of the Iziko Museums, who retrieved the Meermin's blueprints in order to assist with identifying this particular wreck from among possibly more than 30 ships reputed to have run aground in the Struisbaai area since 1673.[5][11]

Work on surveying in the De Mond Nature Reserve on the Cape South Coast began in 2004.[16] An airborne magnetometer survey was used, as the earlier choice, a marine magnetomer survey, was not feasible due to the shallow waters. Magnetometer surveys can readily pick out wreck sites, as iron items from the ships can all be detected by their recognisable "signatures". Twenty-two possible sites were revealed, of which eleven could potentially be the Meermin. Six of the eleven were on land, and were ruled out as being pine-built ships (the Meermin was of oak construction), though all of them were sites of previously-unknown wrecks.[17]

The Iziko South African Museum's travelling exhibition "Finding Meermin" includes updates on the progress of Jaco Boshoff's work with the archaeological research team.[16]

References

- ^ a b Other sources describe the Meermin as a 450-ton, two-masted (A failed bid for freedom, Rebirth Africa, 2000), or single-masted ship (Struisbaai, Western Cape Government, 2005), but the blueprints obtained by archeologist Jaco Boshoff confirm her as one of the more rare (and heavier) oak-built three-masters.(Hunting for a lost ship, Chandler, 2009)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mountain, Alan (2005). An Unsung Heritage: Perspectives on Slavery. Claremont, South Africa: David Philip Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0864866226.

- ^ a b "The Slave Mutiny on the slaver ship Meermin". Cape Slavery Heritage. 2008-3-26. http://cape-slavery-heritage.iblog.co.za/2008/03/26/the-slave-mutiny-on-the-slaver-ship-meermin/. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Educational Broadcasting Corporation (2010-11-07). "Slave Ship Mutiny (episode information)". Educational Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/featured/slave-ship-mutiny-about-this-episode/674/. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b Malan, Antonia (2008). "Unearthing Slavery: the Complex Role of Archaeology". Cape Town, South Africa: Historical Archaeology Research Group, University of Cape Town. http://www.ndstest.co.za/iziko/education/pastprogs/pdfs/2008freedomday_malan.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b c d e f Theal, George McCall (2010). History and Ethnography of Africa South of the Zambesi. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1108023344.url

- ^ Quarterly bulletin of the National Library of South Africa. 59. Friends of the National Library of South Africa. 2005. p. 101. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=l8PjAAAAMAAJ&q=meermin+slave+ship+mutiny&dq=meermin+slave+ship+mutiny&hl=en&ei=MXeuTo_7OInesgaFw4z7BA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Joe (2010-11-11). "Slave Ship Mutiny (Program Transcript)". Educational Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/transcripts/slave-ship-mutiny-program-transcript/755/. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b c d LaFraniere, Sharon (2005-08-24). "Tracing a Mutiny by Slaves Off South Africa in 1766". Utexas.edu. http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/1038.html. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b c d Western Cape Government (2005-11-29). "Places of Slave Remembrance in the Western Cape, Struisbaai". Westerncape.gov.za. http://www.westerncape.gov.za/eng/pubs/public_info/P/82884/5. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Andrew. "The Meermin Story (extracts from Mutiny on the Meermin)". Mermaid Guest House. http://www.mermaidguesthouse.com/index.php?p=Meermin-story. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ^ a b c Rebirth Africa. "Slaves: a failed but bold attempt to escape". Rebirth.co.za. http://www.rebirth.co.za/slaves_a_failed_bid_for_freedom.htm. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Schell, Robert (1994). Children of Bondage: A Social History of the Slave Society at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652–1838. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-0819552730.

- ^ Vollgraaff, Helene (1997). The Dutch East India Company's Slave Lodge at the Cape. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Cultural History Museum. ISBN 978-1875045266.

- ^ Alexander, Andrew (2003). "The Mutiny on the Meermin". Scientific Commons (En.scientificcommons.org). http://en.scientificcommons.org/32299175. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ a b "Finding Meermin". Iziko Museums. http://www.iziko.org.za/calendar/event/finding-meermin. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Chandler, Graham (2009). "Hunting for a lost ship under two and a half centuries of shifting sands". Earthexplorer.com. http://www.earthexplorer.com/2009-11/Hunting_for_a_lost_ship.asp. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

Categories:- Mutinies

- Slavery

- 1760s ships

- Ships of the Dutch East India Company

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.