- Medical treatment during the Second Boer War

-

Stretcher-bearers of the Indian Ambulance Corps during the war, including the future leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Middle row, 5th from left).

Stretcher-bearers of the Indian Ambulance Corps during the war, including the future leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Middle row, 5th from left).

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902, between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal Republic). It was a lengthy war involving large numbers of troops which ended with the conversion of the Boer republics into British colonies, with a promise of limited self-government. These colonies later formed part of the Union of South Africa.

During the Boer war, 22,000 troops were treated for wounds inflicted during battle.[1] The surgical facilities provided by the British army were vastly more effective than in previous campaigns.[2] The Medical Department of the army mobilized 151 staff and regimental units.[3] Twenty eight field ambulances, five stationary hospitals and 16 general hospitals were established to deal with casualties.[3] Numerous voluntary organizations set up additional hospitals, medical units and first aid posts. Around one thousand Indians from Natal were shipped to South Africa to help in the recovery effort by transporting the wounded off the battlefields.[3] Even Mahatma Gandhi, who was practising as a lawyer at the time in Durban, was a volunteer, helping recovery efforts in the Battles of Colenso and Spionkop.[4] A second unit was established by Johannesburg and Cape Town Jews and aided both armies.

Contents

Implications in recovery

British soldiers lie dead on the battlefield after the Battle of Spion Kop, 24th Jan. 1900

British soldiers lie dead on the battlefield after the Battle of Spion Kop, 24th Jan. 1900

In the early battles of the war, the recovery team carrying stretchers would walk onto the battlefield in the firing zone as soon as a man was wounded and carry him off. Soldiers participating in the battle would also help. However,[4] in doing so this reduced the numbers in active battle and the Boers soon gained a reputation for rapid firing at any moving person, soldier or paramedic. As a result, being wounded in the war and recovery was seriously affected, often forcing the casualties to be retrieved after dusk, meaning they had either died or could not be located very easily in the dark.[4]

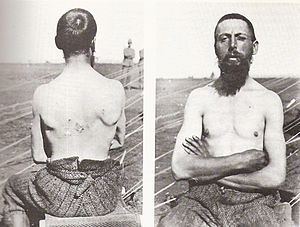

During the early weeks of the war, the Boers were reported to be using poisoned bullets which worsened the infection of British soldier wounds.[5] Although the rifles used in the war were not intended to inflict massive damage, the Boers used German Mauser rifles which were known for creating clean wounds.[5] However the bullets they used, known commonly as "Dum-dums" were made from a soft lead which would expand upon impact or were modified by cutting through the outer case of a normal bullet to affect the way the opposing army was wounded.[5] Boer bullets retrieved from wounded soldiers in the battlefields were often found to contain a green fat coating, which had been used to lubricate the chamber and rifle barrel.[5]

However, many wounded in battle that survived, described the wounds inflicted by the Boers as painless initially but would increase in pain gradually.[5] Many described the experience as being "tapped with a hammer" or "being less painful than the drawing of a tooth".[6] However, many suffered considerably. One British Sergeant shot during the Siege of Ladysmith described the wounding as follows:

“ "As the morning came, firing was very heavy and two Boers were shooting over the very rock behind which I lay...As the sun rose, the heat became intense and the wound gave me anxiety and pain and I could not stop bleeding. I took the puttee off my right leg and tied it tightly above the left knee and tried to stop the dripping but without avail. However, I found that the blood on the ground had congealed in the intense heat."[6] ” Surgical developments and treatment

Of the 22,000 that were treated for wounds during the Second Boer War, the majority survived, largely due to the efficiency of the medical teams which cared for the affected.[1] The Royal Army Medical Corps, which had formed after the redunduncies of the Crimean War, played a key role in the treatment of the wounded in the Boer War. The salaries of medical corps soldiers had gradually increased and training improved, improving the system and quality of the medical services.[7] Surgery had made considerable advancement in the late nineteenth century, and the army surgery facilities were considered state of the art at the time.[7] In 1899 the RAMC had recruited a number of specialist surgeons in its ranks to treat the wounded, including many of notable prestige, including Sir Frederick Treves, 1st Baronet, Sir William Cheyne, 1st Baronet, Sir William MacCormac, 1st Baronet, William Stokes, Kendal Franks and G.L. Cheatle.[7] George Henry Makins, a prominent surgeon during the Boer War published a textbook of military surgery in 1901.[7]

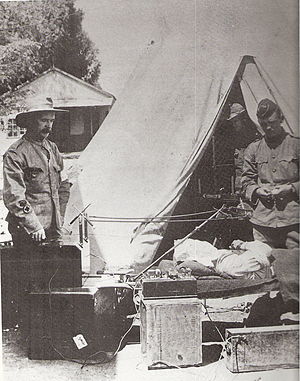

Casualties during the Boer War were generally recovered in stages. Battalion doctors located on the battlefields would take the wounded by stretcher to a dressing station for initial treatment. This included the widespread use of field dressings consisting of a sterile gauze pad stitched to the bandage and covered with waterproofing.[4] Each pack contained two dressings and numerous safety pins.[4] Later they would be taken to ambulances or stationary hospitals where the complex recovery by the surgeons could be carried out. However, given the number of casualties in relation to staff, it was often days before a wounded soldier could see a doctor for full treatment, increasing the extent of the infection of the wounds.[8] As a result primary surgical care was often conducted in ambulances.[8] Many wounds were open fractures and often involved damage to bones. In such cases, the wounds were treated by debridement and the wound packed.[9] The limb would then be immobilized with a splint made of canvas with strips of bamboo sewn in to support it.[9]Plaster of Paris was also used during the Boer War after the bone had been set.[9] The treatment of wounds was greatly enchanced by the invention of X-rays and some 9 machines were taken to South Africa during the campaign.[9]

There was also some success with the treatment of head injuries.[10] However, the medical operations in the Boer War were considerably less successful in treating wounds inflicted in the chest. Conducting abdominal surgery at the side of the battefields was often ineffective given the seriousness of the location of the bullet wound and the limited facilities in the temporary tents for treating such advanced complications. Deaths from chest wounds were of a far greater number than other wounds.[11]

Some atrocities towards wounded Boer soldiers which fell into British hands have been reported. Extracts from British soldiers and generals private letters and documents have revealed some evidence of inhumane activity by the British in encountering the wounded enemy.[12]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b Lee 1985, p. 69.

- ^ Lee 1985, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Lee 1985, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e Lee 1985, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e Lee 1985, p. 66.

- ^ a b Lee 1985, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Lee 1985, p. 68.

- ^ a b Lee 1985, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Lee 1985, p. 78.

- ^ Lee 1985, p. 79.

- ^ Lee 1985, p. 81.

- ^ "Alger on the Boer War" (PDF). New York Times. 5 February 1900. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=940DE7D61239E733A25756C0A9649C946197D6CF. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

Bibliography

- Lee, Emanoel (1985). To The Bitter End:A Photographic History of the Boer War 1899-1902. London: Penguin Books, Viking Penguin Incorporated..

External links

Categories:- Second Boer War

- Military medicine

- Healthcare in South Africa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.