- Ernest Spybuck

-

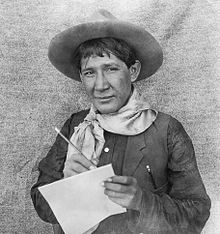

Ernest Spybuck

Ernest Spybuck, Absentee Shawnee Artist. ca. 1910Born January 1883

Potawatomi/Shawnee Reservation, near Tecumseh, OklahomaDied 1949 (aged 66)

On Indian allotment land, 16 miles west of Shawnee, OklahomaNationality Absentee Shawnee, USA Field painting, drawing Training self-taught Movement Native American Fine Art Movement, Early Narrative Genre Influenced by M. R. Harrington Ernest Spybuck (January 1883 – 1949) was a Native American artist.[1] Born on a reservation in Indian Territory, Spybuck was encouraged in his artistic endeavors by a meeting with a visiting anthropologist, M.R. Harrington. His detailed depictions of ceremonies, games and social gatherings were used to illustrate many anthropological publications. Spybuck has been received very positively by both Native American and artistic communities. Many of his works are now held by the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Contents

Early life

Ernest (Earnest) Spybuck was born on the Potawatomi-Shawnee Reservation near Tecumseh, Oklahoma,[2] to the White Turkey Band of the Absentee Shawnee, of the Rabbit clan. His parents were Peahchepeahso and John Spybuck. His Indian name was Mathkacea or Mahthela.[1] He preferred spelling his first name as "Earnest."[3]

By the time he was born, the Shawnee, like many tribes that had originally resided east of the Mississippi River, were largely settled in Indian Territory due to the Indian Removal policies of the U. S. Government. Many different tribal peoples were settled in close proximity to each other, so Spybuck grew up familiar with neighboring Sauk and Fox, Kickapoo, and Delaware peoples.[4]

He attended school at Shawnee Boarding School in Shawnee, Oklahoma and at Sacred Heart Mission in south-central Oklahoma. According to his teacher at Shawnee Boarding School, at the age of eight he would do nothing but draw and paint pictures with subjects drawn from his life. His education never went beyond the Third Reader.[5]

He married at the age of 19, and eventually had three children.[3]

Recognition by M. R. Harrington

Spybuck's career as an artist began early in his life with an encounter with anthropologist Mark Raymond Harrington, in 1910. At the time, Harrington was collecting specimens and researching the tribes of the area for the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. His assistant brought Spybuck to his office, where he was able to examine the young man's "unsophisticated" drawings. He appreciated the detailed accuracy of the equipment and dress depicted, and engaged him to create water colors of ceremonies and social life of the tribes in the vicinity.[3]

Spybuck produced watercolors for Harrington through 1921, and Harrington used some of them in a couple of monographs published by the Heye Foundation.[6] Harrington also interviewed Spybuck for a work on the Shawnee that he never published, but he deposited his notes and Spybuck's paintings with the Museum of the American Indian, which is now the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.[4]

One reviewer discounts the influence of Harrington's patronage, claiming that Spybuck was already committed to depicting daily reservation life at their meeting and that his art matured along with his involvement with his local community, which included participating in the social activities and ceremonies that interested ethnographers.[7]

Artistic style

Spybuck told Harrington that he preferred painting cowboys, livestock, and range scenes, but through Harrington's patronage, Spybuck's style evolved, particularly in his choice of subjects and the way he painted them. He painted in "primitive realism" local scenes of ceremonies, games, social gatherings and home life that he was familiar with and often participated in. His style recalled Plains representative art that often identified individuals by depicting details of dress and accoutrement, but he took the realistic depiction of the figures and setting in a new direction that was uniquely his own.[4]

His "documentary realism" gave meticulous attention to dress, accouterments and gesture,[8] set in a simplified three-dimensional setting with well-defined foreground and background.[9] He developed his own unique techniques, such as painting a cross-section "window" in a tipi or lodge where a ceremony would take place to show the activity inside, while also showing the landscape and time of day outside.[4]

In Western European terms, Spybuck's style might be called naïve art, but his works differs from most naïve artists' due to the influence of ethnographic patronage that guided his choice to include certain details and an infusion of a sense of humor and personality. His scenes can provide subtle hints of attitudes and personalities of individual people and often include whimsical details on the periphery that contrast with the central activities.[7]

Critical responses

Like Harrington, other reviewers recognize that Spybuck possessed a remarkable talent, but it often served a practical purpose in the domain of ethnography. His paintings served as illustrations for numerous anthropological writings. Dobkins calls this practice autoethnography, in which the artist or writer assimilates the techniques of ethnographers to create representations of themselves and their cultures, with the implication of an asymmetrical power relationship between the ethnographer patron and the Native artist. Along with Spybuck, Dobkins names Jesse Cornplanter (Seneca), Peter Pitseolak (Inuit), and Frank Day (Maidu) as artists who practiced autoethnography to regain control over representations of their cultures and to retrieve and preserve their traditions.[10] Other reviewers recognize Spybuck as an Indian artist who is a recorder and preserver of traditional practices in the midst of social change.

In Spybuck's life, works by Native American artists were beginning to become exhibited as art rather than ethnographic specimens. Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century was an exhibit that opened at the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona in 1991 and then toured to four major museums in the United States. The exhibition brought together three generations of artists to trace the history of the Native American Fine Art Movement. Together with Arapaho artist Carl Sweezy, the exhibit placed Spybuck in the earliest stage of the movement, Early Narrative Style, in which Native artists documented the upheavals in Indian Country in the late 19th century and early 20th century. They adopted and adapted western techniques of art and ethnography to produce works that documented the transformation of traditional ways under the restrictions of reservation life. [11]

Later life

Spybuck worked as a farmer, painter, and historical informant.[1] He belonged to a large and influential family within the Absentee Shawnee Nation where he was an active member of the community and became a Peyote leader when the Native American Church was first adopted by Shawnee people.[11] He died in 1949 at the age of 66 and was buried in a family plot near his home.[1]

It has been noted that by his mid-50s he had never left the county of his birth.[5] In addition to having his art published in many books on American Indian cultures, several museums purchased his work for their collections. He was commissioned to produce murals for the Creek Indian Council House and Museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma and at the Oklahoma Historical Society Museum in Oklahoma City. During his life his work was exhibited at the Museum of the American Indian in New York City and at the American Indian Exposition and Congress in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[1]

Works

Publications that include Spybuck art

- Harrington, M. R. (1914). Sacred bundles of the Sac and Fox Indians. The university museum anthropological publications. IV(2). Philadelphia: The University Museum.

- Harrington, M. R. (1921). Hodge, F. W.. ed. Religion and ceremonies of the Lenape. Indian notes and monographs. New York: Museum of the American Indian Heye Foundation. http://www.archive.org/stream/religionceremoni00harr#page/n7/mode/2up. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Underhill, Ruth M. (1965). Red man's religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-84166-9.

- La Farge, Oliver (1957). A pictorial history of the American Indian. New York, N.Y.: Crown Publishers, Inc..

- Grumet, Robert S., ed (2001). Voices from the Delaware Big House Ceremony. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3360-6.

- La Farge, Oliver. The American Indian: Special edition for young readers. New York: Golden Press. ISBN 60-14881.

- Brody, J. J. (1971). Indian painters & white patrons. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826301925.

- Silberman, Arthur 1978. 100 years of native American painting. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Museum of Art.

- Hightower, Jamake (1978). Many smokes, manymoons: A chronology of American Indian history through Indian art. New York: J. B. Lippincott. ISBN 978-0397317813.

- Fawcett, David M.; Callander, Lee A. (1982). Native American painting : selections from the Museum of the American Indian. New York: Museum of the American Indian.

- Callander, Lee A.; Ruth Slivka (1984). Shawnee Home Life: The Paintings of Earnest Spybuck. New York, N.Y.: Museum of the American Indian. p. 7. ISBN 0-934490-42-2.

- Archuleta, Margaret; Dr. Rennard Strickland (1991). Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century. Phoenix, Arizona: The Heard Museum. ISBN 1-56584-069-0.

Major exhibitions

- Shawnee Home Life: The Paintings of Earnest Spybuck

- Opened at the Museum of the American Indian, New York, New York in 1987, then toured to several museums, including

- The Oklahoma Historical Society Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Bacone College Museum, Muskogee, Oklahoma

- Shared Visions: Native American Painter and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century

- Opened at the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, on April 13, 1991, then toured to

- The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis, Indiana

- The Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- The Oregon Art Institute, Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon

- The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, The U.S. Custom House, New York, New York

Collections

- National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

- Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

- Oklahoma Historical Society Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Norman, Oklahoma

See also

- List of indigenous artists of the Americas

- List of Native American artists

References

- ^ a b c d e Lester, Patrick D. (1995). The Biographical Directory of Native American Painters. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806199369.

- ^ "SPYBUCK, ERNEST (1883-1949)". Digital.library.okstate.edu. Oklahoma State University. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/S/SP017.html. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- ^ a b c Harrington, M. R. (1938). "Spybuck, the Shawnee Artist". Indians at Work (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior Office of Indian Affairs) 5 (8): 13–15.

- ^ a b c d Callander, Lee A.; Ruth Slivka (1984). Shawnee Home Life: The Paintings of Earnest Spybuck. New York, N.Y.: Museum of the American Indian. p. 7. ISBN 0-934490-42-2.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Jeanne O. (1968). American Indian Painters: A Biographical Directory. New York: Museum of he American Indian Heye Foundation. p. 179.

- ^ M. R. Harrington (2008). Religion and Ceremonies of the Lenape. READ BOOKS. ISBN 9781408648520. http://books.google.com/?id=ZmiqTtfjUqEC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10&dq=ernest+spybuck#v=onepage&q=ernest%20spybuck&f=false.

- ^ a b Smith, Kevin (1998). Matuz, Roger. ed. St. James guide to native North American artists. Detroit, MI: St. James Press. p. 536.

- ^ Townsend-Galt, Charlotte (1993). "Impurity and Danger". Current Anthropology (University of Chicago Press) 34 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1086/204142. JSTOR 2743739.

- ^ Marshall Gettys (2007). "SPYBUCK, ERNEST (1883-1949)". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Oklahoma State University. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/S/SP017.html. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Dobkins, Rebecca J. (2001). "Art and Autoethnography: Frank Day and the Uses of Anthropology". Museum Anthropology (American Anthropological Association) 24 (2/3): 22–29. doi:10.1525/mua.2000.24.2-3.22.

- ^ a b Archuleta, Margaret; Dr. Rennard Strickland (1991). Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century. Phoenix, Arizona: The Heard Museum. p. 7. ISBN 1-56584-069-0.

External links

- "Images of Ernest Spybuck's work in the Smithsonian's collection". National Museum of the American Indian. http://www.nmai.si.edu/searchcollections/results.aspx?hl=396. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- "Photographs of Ernest Spybuck in the Smithsonian's collection". National Museum of the American Indian. http://www.nmai.si.edu/searchcollections/results.aspx?catids=4&partytxt=Earnest+Spybuck&src=1-2. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- Harrington, M. R. (1921). Religion and ceremonies of the Lenape. New York, Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. http://www.archive.org/stream/religionceremoni00harr#page/n7/mode/2up.

- "Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art: Collections Native American Art". Ou.edu. 2008-05-09. http://www.ou.edu/artcollections/collections/native_american/Native%20American/Spybuck_StompDance.html. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- "SPYBUCK, ERNEST (1883-1949)". Digital.library.okstate.edu. Oklahoma State University. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/S/SP017.html. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

North American Indigenous visual artists American Indian Basket weavers • Bead artists • Conceptual • Drawing • Filmmakers • Illustrators • Installation • Jewelers • Painters • Performance • Photographers • Potters • Printmakers • Sculptors • Textiles • WoodcarversFirst Nations Basket weavers • Conceptual • Filmmakers • Installation • Jewelers • Painters • Performance • Photographers • Potters • Printmakers • Sculptors • Textiles • Woodcarvers

Indigenous Mexicans Illustrators • Painters • Performance • Photographers • Printmakers

Inuit Filmmakers • Illustrators • Painters • Photographers • Printmakers • Sculptors • Textiles

Maya Illustrators • Painters • Printmakers

Mestizo Painters

Métis Filmmakers • Installation • Painters • Performance • Printmakers

Categories:- Native American painters

- Native American illustrators

- 1883 births

- 1949 deaths

- People from Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma

- Shawnee people

- Painters from Oklahoma

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.