- Jerome Lyle Rappaport

-

Jerome Lyle Rappaport

Born August 17, 1927

New York CityResidence Boston, Massachusetts Nationality United States Alma mater Harvard University Spouse Phyllis Rappaport Jerome Lyle Rappaport[1] (born August 17, 1927) was a lawyer, developer, political leader, and landlord. Today, he is best known for his philanthropy in Boston, Massachusetts, and as the general partner of one of the most successful and maligned developments of the urban renewal era, the West End Project from which he created a 48-acre (190,000 m2) urban neighborhood known as Charles River Park.[2][3]

Contents

New York and Harvard Roots

Born and raised in the Bronx and Manhattan’s Upper West Side, being the son of a clothier of Romanian extraction.[4] Rappaport entered Harvard University at 16 years old and received his Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws at 21 in 1949. He earned a Masters of Public Administration from the Littauer School (today the Harvard Kennedy School) in 1963.[5]

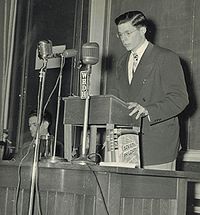

As a student Rappaport founded the Harvard Law School Forum, which was originally dedicated to the memory of Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. and 102 other Harvard Law School graduates and former students on leave who had died in World War II. The Forum’s Friday evening radio broadcasts on WHDH in 1946 garnered positive press and inspired the participation of Harvard’s then President, Law school Dean, faculty members and student peers.[6]

Early Success in Politics

In the early 1950’s Rappaport quickly emerged as one of Boston’s most well-known political leaders.[7] The peak occurred when Rappaport succeeded Congressman John F. Kennedy in receiving the Massachusetts Jaycees “Distinguished Service” award as Massachusetts’ most Outstanding Young Leader for 1952. Kennedy's award was one of many stepping stones on the road to his becoming a United States Senator. Rappaport’s acceptance speech in January 1953 was mostly geared towards inspiring wealthier and more seasoned local businessmen to invest everything they could in Boston’s then-languishing economic development program, and "to give more time, energy, and thought to community affairs."[8]

Prior to that his efforts helped John Hynes beat James Michael Curley in the watershed city elections of 1949.[9] The following year Rappaport started to become a centerpiece of Boston’s political reform movement when he created the New Boston Committee (NBC). Rappaport received national attention while Curley’s popularity spiraled downward. The NBC reached its highest point when ten of the fifteen elected officials who served the city from 1952-1954 had been endorsed by the NBC. After Curley's unsuccessful attempt to dismiss the NBC, as a reincarnation of the so-called "Goo-goos" that he had rallied working class Bostonians against for years, Curley said that he quit the 1951 mayor’s race because it was “imperative that...all the candidates endorsed by the New Boston Committee be defeated.”[10] Six years later, Rappaport was one of the so-called "enemies" Boston’s Rascal King aimed to bury through disparaging remarks published in Curley’s autobiography, "I'd Do It All Again."[11]

During this period Rappaport also worked in the John Hynes Administration, established a private law office, and taught a political science class at Boston University.[12] He earned public praise for creating the short-lived Greater Boston Area Council (GBAC), which indirectly led to the creation of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council and Greater Boston’s first public television station, WGBH-TV Channel 2.[13]

Urban Renewal builder

Less than two years after the NBC and GBAC disbanded during the summer of 1954, Rappaport, Seon Pierre Bonan (a Connecticut and New York City-based developer) and Theodore Shoolman (a Boston Realtor whose late father had built The Wang Theatre) began a forty year business partnership by acquiring the rights to redevelop Boston’s West End neighborhood, as part of the national urban renewal program launched by the Housing Act of 1949. After a sixteen-year construction phase the West End Project was ultimately successful. It launched a long era of luxury housing construction in Boston that slowed decades of decentralization. Throughout the 1960s Charles River Park symbolized the critical early successes of the "New Boston," the city’s political and economic rebound during the last half of the 20th Century.[14]

Mixed legacy

Rappaport has been commended publicly and received lifetime achievement awards from the American Jewish Committee and Greater Boston Real Estate Board for being an accomplished real estate pioneer and industry leader, a generous philanthropist, and one of the principal architects of the New Boston. He received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Suffolk University in 1998, for "his career of outstanding accomplishments and public service and for his role in reshaping the city's West End neighborhood."[15]

His reputation has also been negatively impacted by a chorus of scholarly and non-scholarly opinions about urban renewal and, in particular, his signature development which resulted from the City of Boston’s decision to gentrify a working class neighborhood. The most widely known book on the subject is "The Urban Villagers," Herbert J. Gans critical analysis of the old area's clearance as an alleged "slum" and the West Enders' displacement from their neighborhood. The West End-Charles River Park experience has been covered thousands of times in books, magazine articles, newspaper columns, and undergraduate and postgraduate papers.

Today, urban planning students are still asked to consider if the positive value of the thriving 50 year-old community that Rappaport and his partners created—consisting of 2,300 units of skyscraper housing, 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) of retail and office space, 3,400 parking spaces, and an affordable housing building for senior citizens—is outweighed by the destruction of the old West End, and the negative experiences of many whom the City evicted prior to this seminal political, economic and urban planning event.[16]

For years the West End controversy cast a shadow over Rappaport’s successful law practice, and profitable developments in New Haven, Connecticut and Brighton, Massachusetts. It is not widely known that he was the first developer to rebuild a section of the then-decrepit and now-flourishing Charlestown Navy Yard, or that he served on the Boston Fair Housing Commission and the boards of numerous non-profits and corporations for a period spanning more than half a century. Even after the real estate investment company he formed with two sons, New Boston Fund Inc. became one of the richest and most powerful in New England during the late 1990’s, nearly every major article about Rappaport mentioned the West End Project and cast it in a mixed light.(Source: “Controversy is Rappaport’s Middle Name.” Boston Globe, April 11, 1990)

Philanthropy

Jerry and Phyllis Rappaport attending an October 2009 event hosted by the Rappaport Center and the Ford Hall Forum.

Jerry and Phyllis Rappaport attending an October 2009 event hosted by the Rappaport Center and the Ford Hall Forum.

In 1997 Rappaport and his wife established the Phyllis and Jerome Lyle Rappaport Charitable Foundation.[17] It has since donated more than $30 million to efforts focusing on public policy, health, and the arts.[18] The bulk of the money has gone to the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston at Harvard Kennedy School, and the Rappaport Center for Law and Public Service at Suffolk University Law School.[19]

Notes

- ^ Also known as Jerry Rappaport, Jerome Rappaport, and Jerome L. Rappaport

- ^ "Rappaports permanently endow institute." Harvard University Gazette, September 14, 2006. [1].

- ^ "West End Won’t Be Waterloo." Boston Herald, September 15, 2003.

- ^ “Controversy is Rappaport’s Middle Name.” Boston Globe, April 11, 1990.

- ^ "Rappaport Gets Housing Post," Boston Globe, October 26, 1982.

- ^ See HLS Forum website at www.law.harvard.edu/students/orgs/forum/index.html. See also “The Forum as an Adjunct of Legal Education,” Journal of the American Bar Association, March 8, 1946; and an article about Rappaport in the Boston Sunday Herald, February 6, 1949.

- ^ “A Young Fresh Wind Blows in Boston Town,” Reader’s Digest, April 1952. See also “Youth Wins Against Misrule,” Redbook Magazine, March 1952; and “New Boston Committee Plunges Into Long-Range Plans to Consolidate Election Victories—Rapped by Opponents—Widespread Program—Grassroots Effort—Credit to Rappaport—No Rosy Path,” Christian Science Monitor, November 7, 1951.

- ^ “Boston’s Businessmen Prodded By Rappaport.” Christian Science Monitor, January 17, 1953.

- ^ New York Times, September 27, 1951. See also, Time Magazine, October 8, 1951.

- ^ Boston Herald, October 3, 1951. See also New York Times, October 7, 1951.

- ^ “I’d Do It Again,” by James Michael Curley. Prentiss-Hall (1957).

- ^ Boston University News, February 12, 1952.

- ^ Boston Sunday Globe, October 11, 1953. See also South End Citizen, November 25, 1952.

- ^ Boston Globe, July 30, 1970.

- ^ New England Real Estate Journal, June 12, 1998.

- ^ “West End Won’t Be Waterloo." Boston Herald, September 15, 2003.

- ^ See http://www.rappaportfoundation.org/

- ^ “Going Beyond Alma Mater, Rappaport boosts Suffolk.” Boston Globe, December 10, 2006. See also “KSG Gets $12 Million To Study Boston.” Harvard Crimson, June 30, 2006.

- ^ See [2]; [3]; and [4].

Categories:- Massachusetts lawyers

- American philanthropists

- American people of Romanian descent

- 1927 births

- Living people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.