- Cuppacumbalong Homestead

-

Cuppacumbalong is an historic homestead located near the southern outskirts of Canberra in the Australian Capital Territory. It is also the name of a former 4,000-acre (16 km2) sheep and cattle grazing property that surrounded the homestead near the junction of the Murrumbidgee and Gudgenby Rivers. The word Cuppacumbalong is Aboriginal for 'meeting of the waters'. One of the property's early owners Leopold de Salis made a noteworthy contribution to political life during colonial times and furthermore, Cuppacumbalong has strong connections to the life of William Farrer, the father of the Australian wheat industry.

Contents

James Wright

Englishmen James Wright and a friend John Hamilton Mortimer Lanyon migrated to Australia during the early 1830s. In 1833 they were amongst the first squatters to established sheep runs in the Queanbeyan region, building the Lanyon Homestead. In 1835 they acquired several adjoining blocks on the Murrumbidgee River. Wright established Cuppacumbalong located on the southern side of the Murrumbidgee River in 1839. At the time this region was situated outside the Nineteen Counties of New South Wales and despite the uncertainty of land tenure, many squatters ran large numbers of sheep and cattle beyond the boundaries. By one current-day account 'Cuppacumbalong' stretched 30 miles (48 km) southward to presentday Bredbo.[1] In 1848 financial difficulties forced Wright to sell Lanyon to Andrew Cunningham and shift his operations to Cuppacumbalong. Wright sold 'Cuppacumbalong' to the de Salis family in 1855.

De Salis family

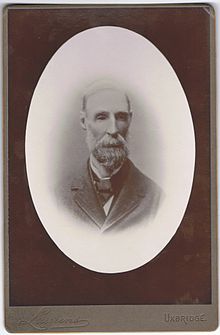

Count Leopold, aged c77. Photograph taken in Uxbridge, Middlesex, west of London, 1893

Count Leopold, aged c77. Photograph taken in Uxbridge, Middlesex, west of London, 1893

Leopold Fabius Dietegen Fane de Salis (1816–1898), pastoralist and politician, was born on 26 April 1816 in Florence, Italy, the fourth son of Jerome Fane, fourth Count de Salis, the third son by his third wife Henrietta, a daughter of William Foster (bishop). Sir William Foster Stawell, later the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the colony of Victoria was his first cousin.

De Salis was educated at the English public school Eton College, before moving onto further studies in sheep farming near Jedburgh, in Scotland. In 1840 at the age of 24, de Salis migrated to New South Wales where he acquired with a partner the 'Darbalara Station' located on the Murrumbidgee River near Yass. In 1845 he was one of the principal squatters that opened up the Riverina district to agriculture, establishing a run he called Jewnee pastoral station as well as two others over a 8 year period. After he disposed of these interests, the village (later the township) of Junee was established on this site.[2] He married Charlotte MacDonald in 1844 with whom he had five children; Leopold William (1845–1930), Rodolph (1841–1876), George Arthur Charles, Henry Gubert (1858–1931) and Nina. In 1855 the de Salis family bought and relocated to 'Cuppacumbalong' Station.

Cuppacumbalong was at this time noted for its especially fine wool and magnificent draught horses.[3] De Salis completed a number of property improvements such as crop irrigation and was a local pioneer in the use of stock dams. The homestead was situated low to the river and was subsequently inundated on a number of occasions by flood waters during de Salis' time.[4]

Within 6 years of the family's arrival in the Queanbeyan district the Robertson Land Acts was passed into law in New South Wales. These measures were designed to wrest control of land away from the squatocracy and encourage the takeup of land by smaller more productive landholders (selectors). De Salis quickly registered several parcels of land under the names of various family members and dummies to retain ownership of 'the flats', the riverflats that backed onto the Murrumbidgee River.[5] In doing so he eventually consolidated his family's land holding and 'converted' his squatter run into a de facto 'freehold estate'.

Leopold's only daughter Nina married scientist William Farrer in 1882.[6] De Salis gave the newly-weds 97 hectares of his property, which the Farrers later named Lambrigg.

In 1869 the de Salis family acquired the Nass; and Nass Valley squatting runs located in Upper Murrumbidgee area and later still purchased the Coolemon run high in the Brindabella Ranges. Later in the 1870s his sons acquired stations in Queensland, most notably Strathmore, located near the township of Bowen. Leopold's immediate elder brother William Fane De Salis held a number of positions including the chairmanship of the London Chartered Bank of Australia. William used his financial connections to help his brother finance these pastoral operations.

Leopold de Salis was elected the Local Member for Queanbeyan in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly where he served local constituents from 1864–69. Then in July 1874 he was appointed to the New South Wales Legislative Council. In a political career spanning 24 years, de Salis pursued taxation reform, specifically income tax, that required labourers contribute 'as an insurance against misfortune or improvidence'.[7]

The de Salis family later fell victim to the financial crisis of the 1890s and the Union bank foreclosed on the family's Queensland land holdings in 1892. Leopold visited England in 1893, when the accompaying photograph was taken. The de Salis family remained at Cuppacumbalong until 1894. Leopold was declared insolvent four years later with a debt of £100,000 shortly before his death.

Leopold de Salis is commemorated in Canberra by the naming of De Salis Street, in the suburb of Weetangera in which all the streets are named for regional pioneer settlers.[8]

Various owners

Cuppacumbalong passed through the hands of two sets of owners during the first two decades of the 20th century. Colonel Selwyn Campbell was in partnership with George Circuitt who was married to a daughter of Mr Crace of Gungahleen of the Ginninderra district. Campbell and co lived there for 13 years until August 1911, having sold the 20,939-acre (84.74 km2) estate to A.G. McKeahnie of Queanbeyan.[3][9] A new owner Alan Thomson acquired the property after this time. Thomson built a new homestead at a point high above the Murrumbidgee River flood plain overlooking the old homestead which he later demolished .[10]

Snow family

Frank Snow who originated from Ballarat in central Victoria acquired Cuppacumbalong in the early 1920s.[11] He completed extensive additions to the Thomson homestead. This modern bungalow offered beautiful views of the surrounding country side from the terraces where frilly petunias cascaded over the walls and brightly coloured parrots amongst the hawthorns and the giant arbutus.[3]

The Snow family played host to a number of international guests most notably the then UK Opposition Leader and future Prime Minister Anthony Eaton and later still Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh during their 1952 Australian Royal tour.[12]

The Snow family continued with the wool tradition running about 7,000 head of Merino sheep and 300 head of Hereford cattle. In addition they operated a small Romney Marsh sheep stud.[12] At 7,700 acres (31 km2) in size Cuppacumbalong was one of the largest freehold rural properties remaining in late 1960s.

Commercial uses

In the early to mid 1970s the Federal Governments under Prime Ministers William McMahon and Gough Whitlam withdrew the rural leases for Lanyon, Cuppacumbalong Homestead and Gold Creek Homestead.[13] In 1975, Karen O’Clery leased Cuppacumbalong Homestead from the Department of the Capital Territory and established the Cuppacumbalong Craft Centre, with a cafe, exhibition rooms, two permanent studios (later extended to three). Later still a shop was opened displaying studio output and other craft work.[14]

With a change of lease in 1999, the Cuppacumbalong Homestead became a restaurant and wedding reception centre.[15] A separate cottage gallery continued to exhibit and sell Australian craftwork. Then one year after the disastrous 2003 Canberra bush fires, business was dealt a fatal blow. The Tharwa bridge was closed, both Cuppacumbalong businesses suspended operations. The current lessees plan to convert the homestead to a private residence and to build a separate gallery and bakery cafe.[16]

Heritage site

All three Cuppacumbalong homesteads, including the ones constructed by James Wright, the de Salis and Snow families are included on the ACT Heritage Register.

The citation of the Heritage Register states that:

the remains of the first (Wright) homestead and the second (De Salis) homestead are important archaeological sites associated with the first settlement of the area.[17] The current homestead which dates from 1923 is a good, relatively rare and reasonably intact example of the Inter-War California Bungalow style in the ACT. It is one of only a few known examples of this style in the ACT.[17]

The de Salis family grave is also sited at Cuppacumbalong and about 16 people associated with to the de Salis family including the count, his wife, their second son and station staff are buried there.[18]

The de Salis family planted stands of Lombardy poplars alongside the riverfront at Tharwa.

External links

References

- ^ Anthony de Salis. Conversation with Christine James, 2005.

- ^ Sutherland J (1999), A Short History of the Riverina Wheat Industry, New South Wales Heritage Office

- ^ a b c Nesta Griffiths G (1952), Some Southern Homes of New South Wales, The Shepherd Press

- ^ Miss de Salis recalled that a flat bottomed boat was kept tied to one of the verandah posts in times of floods to provide a means of escape

- ^ Stuart Iain (2000), Squatting Landscapes in South-Eastern Australia (1820–1895) unpublished PhD thesis, University of Sydney

- ^ Dixon T (2007), Under the Spell of the Ages: Australian Country Gardens, National Library of Australia

- ^ 'de Salis, Leopold Fabius Dietegan Fane (1816–1898): Australian Dictionary of Biography: Volume 4, Melbourne University Press, (1972)

- ^ Place name search, Government of the Australian Capital Territory

- ^ See Queanbeyan Age newspaper of 29 August 1911, Page 2.

- ^ Dowling P (2007), Tharwa and Lanyon: Self guided tour, National Trust of Australia (ACT)

- ^ Newman C, Interview with Joan Gorman nee Snow, 29 March 2009

- ^ a b Couple to stay at Cuppacumbalong, Friday 11 January 1952, Canberra Times

- ^ Newman Chris (2004), Gold Creek, Reflections of Canberra's Rural Heritage, Gold Creek Homestead Working Group.

- ^ Janet Mansfield, “Cuppacumbalong 15 years strong”, Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 1, 1990, pp. 64–66

- ^ Canberra Times, 27 June 1999, Historic Tharwa property goes up for auction

- ^ [Article about the current lessees' plans], Canberra Times, 21 June 2007, p.7

- ^ a b ACT Heritage Council (2004), Entry to the ACT Heritage Register

- ^ Cuppacumbalong Cemetery Canberra

Categories:- Buildings and structures in Canberra

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.