- Sino-Sikh War

-

Sino-Sikh war

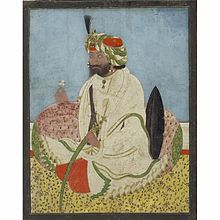

General Zorawar Singh (1786-1841)Date May, 1841 - August, 1842 Location Tibet and Ladakh Result Partial Qing victory Territorial

changesStatus quo ante bellum Belligerents  Qing Empire

Qing Empire Sikh Empire

Sikh EmpireCommanders and leaders Meng Bao

HaipuGulab Singh

Zorawar Singh †The Sino-Sikh War or Sino-Dogra War was fought from May of 1841 to August of 1842 between the Qing Empire and the forces of the Sikh governor of Jammu, Gulab Singh, after he invaded western Tibet. The Dogra army was routed and the Qing counterattacked but were defeated in Ladakh. The Treaty of Chushul was signed in 1842 maintaining the status quo ante bellum.

Contents

Background

From the early XVIII century, the Manchu Qing Empire had consolidated its control of Tibet after defeating their powerful rivals, the Dzungar Khans. Since then until late into the XIX century, the Qing's rule of the region remained unchallenged. South of the Himalayas, the Sikh Empire was established in 1799 and it expanded itself by filing the vacuum that left the weakening of the Durrani Empire.

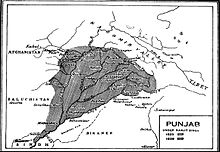

Ranjit Singh's empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, to Sindh in the south, and Tibet in the east. In 1808 Ranjit Singh conquered the Dogras, Rajput hill men from Dougar Desh in Jammu,[1] and incorporated into his empire as vassals. They became an important component of the Sikh army and eventually regain their independence. Meanwhile in the east, Gulab Singh's General Zorawar Singh extended Dogra authority over the Suru valley and Kargil (1835), the rest of Ladakh (1836–40), and Baltistan (1840). Eventually these conquests collided with Sikh authority in Kashmir so Gulab Singh decided instead to extend his authority to the east into Tibet.

The reasons for the invasion are still debated among historians, some say control of Tibet would have gave Gulab Singh a monopoly on the lucrative pashmina wool trade of Tibet, other believe that his objective was to establish a land bridge between Ladakh and Nepal to create a Sikh-Gorkha alliance against the British.[2]

Zorawar Singh knew that Ü-Tsang (western Tibet) was connected to the rest of Tibet by the Mayum pass so his plan consisted of advancing as quickly as possibly into enemy land, capturing the pass before winter, and building up his forces for a renewed campaign in the summer.[3]

Sikh invasion of Tibet

With the Dogra ambitions clashing with the Punjabi empire in the west, Zorawar Singh turned his energies eastward, towards Tibet. As he had done in Ladakh, so too in the newly-conquered Baltistan, Zorawar recruited the Baltis in his army, which now had men from the Jammu hills, Kishtwar, and Ladakh. This five or six thousand strong army was divided into three columns that marched parallel into Tibet in May 1841.

One column under the Ladakhi prince, Nono Sungnam, followed the course of the Indus River to its source. Another column of 300 men, under Ghulam Khan, marched along the mountains leading up to the Kailas Range and thus south of the Indus. Zorawar himself led 3,000 men along the plateau region where the vast and picturesque Pangong Lake is located. The invaders met with success in the beginning of the invasion, thanks to the quality of their weapons, but the Tibetans resisted using guerrilla tactics and their knowledge of the local terrain.[4] Sweeping all resistance before them, the three columns passed the Mansarovar Lake and converged at Gartok, defeating the small Tibetan force stationed there. The enemy commander fled to Taklakot but Zorawar stormed that fort on September 6, 1841. Envoys from Tibet now came to him as did agents of the Maharaja of Nepal, whose kingdom was only fifteen miles from Taklakot.

The Sikh army now controlled the urban centers of Daba, Tholing, Tsaparang Rudok, Gartok and Taklakot (Purang).[5] He garrisoned the towns and set up an administration to rule the occupied territories. Meanwhile in the Punjab, the British envoys pressured the Maharaja to order his withdrawal while the Nepalis helped the Qing forces against him.[5]

The fall of Taklakot finds mention in the report of the Chinese Imperial Resident, Meng Pao, at Lhasa:

On my arrival at Taklakot a force of only about 1,000 local troops could be mustered, which was divided and stationed as guards at different posts. A guard post was quickly established at a strategic pass near Taklakot to stop the invaders, but these local troops were not brave enough to fight off the Shen-Pa (Dogras) and fled at the approach of the invaders. The distance between Central Tibet and Taklakot is several thousand li…because of the cowardice of the local troops; our forces had to withdraw to the foot of the Tsa Mountain near the Mayum Pass. Reinforcements are essential in order to withstand these violent and unruly invaders.

Zorawar and his men went on pilgrimage to Mansarovar and Mount Kailash. He had extended his communication and supply line over 450 miles of inhospitable terrain by building small forts and pickets along the way. The fort Chi-T’ang was built near Taklakot, where Mehta Basti Ram was put in command of 500 men, with 8 or 9 cannon. With the onset of winter all the passes were blocked and roads snowed in. The supplies for the Dogra army over such a long distance failed despite Zorawar’s meticulous preparations.

As the intense cold, coupled with the rain, snow and lightning continued for weeks upon weeks, many of the soldiers lost their fingers and toes to frostbite. Others starved to death, while some burnt the wooden stock of their muskets to warm themselves. The Tibetans and their Chinese allies regrouped and advanced to give battle, bypassing the Dogra fort of Chi-T’ang. Zorawar and his men met them at the Battle of To-yo on December 12 of 1841, in the early exchange of fire the Rajput general was wounded in his right shoulder but he grabbed a sword in his left hand. The Tibetan horsemen then charged the Dogra position and one of them thrust his lance in Zorawar Singh’s chest. Wounded and unable to scape he was pulled down of his horse and beheaded.[4] The battle marked the end of the invasion, with the death of their General and 300 dead and 700 soldiers captured,[4] the Sikh-Dogra army hurriedly retreated to Ladakh with the Sino-Tibetan forces on their heels until they finally halted the pursuit just a day far from Leh.[6]

Qing invasion of Ladakh

The Sino-Tibetan force then mopped up the other garrisons of the Dogras and advanced on Ladakh, now determined to conquer it and add it to the Imperial Chinese dominions. However the force under Mehta Basti Ram stood a siege for several weeks at Chi-T’ang before escaping with 240 men across the Himalayas to the British post of Almora. Within Ladakh the Sino-Tibetan army laid siege to Leh, when reinforcements under Diwan Hari Chand and Wazir Ratnu came from Jammu and repulsed them. The Tibetan fortifications at Drangtse were flooded when the Dogras dammed up the river. On open ground, the Chinese and Tibetans were chased to Chushul. The climactic Battle of Chushul (August, 1842) was won by the Dogras who executed the enemy general to avenge the death of Zorawar Singh.

The Treaty of Chushul

At this point, neither side wished to continue the conflict, as the Sikhs were embroiled in tensions with the British that would lead up to the First Anglo-Sikh War, while the Chinese was in the midst of the First Opium War with the British East India Company. The Chinese and the Sikhs signed a treaty in September 1842, which stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.[7]

“On this auspicious occasion, the second day of the month Asuj in the year 1899 we —- the officers of Lhasa, viz. firstly, Kalon Sukanwala, and secondly Bakshi Sapju, commander of the forces of the Empire of China, on the one hand, and Dewan Hari Chand and Wazir Ratnu, on behalf of Raja Gulab Singh, on the other —- agree together and swear before God that the friendship between Raja Gulab Singh and the Emperor of China and Lama Guru Sahib Lassawala will be kept and observed till eternity; for the traffic in shawl, pasham, and tea. We will observe our pledge to God, Gayatri, and Pasi. Wazir Mian Khusal Chu is witness.”

See also

Notes

References

- Heath, Ian (2005). The Sikh Army 1799-1849. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841767778. http://books.google.com/books?id=YIh9eQlojGsC.

- Maher, Derek F.; Shakabpa, W. D. (2010). One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet. 1. BRILL. ISBN 9004177884, 9789004177888. http://books.google.com/books?id=lGyrymfDdI0C.

- McKay, Alex (2003). History of Tibet. Routledge. ISBN 0700715088, 9780700715084. http://books.google.com/books?id=l6eTjiivK-UC.

- Bakshi, G. D. (2002). Footprints in the snow: on the trail of Zorawar Singh. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 8170622921, 9788170622925. http://books.google.com/books?id=4S99oXkx_-cC.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.