- Peak programme meter

-

A peak programme meter (PPM) is an instrument used in professional audio for indicating the level of an audio signal.

There are many different kinds of PPM. They fall into broad categories:

- True peak programme meter. This shows the peak level of the waveform no matter how brief its duration.

- Quasi peak programme meter (QPPM). This only shows the true level of the peak if it exceeds a certain duration, typically a few milliseconds. On peaks of shorter duration, it will indicate less than the true peak level. The extent of the shortfall is determined by the 'integration time'.

- Sample peak programme meter (SPPM). This is a PPM for digital audio which shows only peak sample values, not the true waveform peaks (which may fall between samples and be up to 3 dB higher in amplitude). It may have either a 'true' or a 'quasi' integration characteristic.

- Over-sampling peak programme meter. This is a sample PPM in which the signal has first been over-sampled, typically by a factor of four, to alleviate the problem with a basic sample PPM.

Contents

In professional usage, where consistent level measurements are needed across an industry, audio level meters often comply with a detailed formal standard. This ensures that all meters that comply with the standard will give the same indication on a given audio signal. The principal standard for PPMs is IEC 60268-10. It describes two different quasi-PPM designs which have their roots in meters originally developed in the 1930s for the AM radio broadcasting networks of Germany (Type I) and the United Kingdom (Type II).

The term Peak Programme Meter usually refers to these IEC-specified types and similar designs.

PPMs were originally designed for monitoring analogue audio signals but are also now used with digital audio.

PPMs do not provide effective loudness monitoring. Newer types of meter do, and there is now a push within the broadcasting industry to move away from traditional level meters such as those featured in this article to two new types: loudness meters based on EBU Tech. 3341 and oversampling true PPMs. The former would be used to standardise broadcast loudness to −23 LUFS and the latter to prevent digital clipping.[1]

Design characteristics

Display technologies

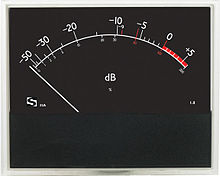

In common with many other types of audio level meter, PPMs originally used electro-mechanical displays. These took the form of moving-coil panel meters or mirror galvanometers with demanding 'ballistics': the key requirement being that the indicated level should rise as quickly as possible with negligible overshoot. These displays require active driver electronics.

Nowadays PPMs are often implemented as 'bargraph' incremental displays using solid-state illuminated segments in a vertical or horizontal array. For these, IEC 60268-10 requires a minimum of 100 segments and a resolution better than 0.5 dB at the higher levels.

Many operators prefer the moving-coil meter type of display in which a needle moves in an arc, because an angular movement is easier for the human eye to monitor than the linear movement of a bargraph.[2]

PPMs can also be implemented in software: this can be done on a general-purpose computer or by a dedicated device which can 'burn in' a PPM image onto a video waveform for display on a picture monitor.

Scales and scale marks

PPMs often use white-on-black displays, to minimise eyestrain especially with extended periods of use.

PPMs are usually calibrated in one of these ways:

- In decibels relative to Alignment Level (e.g. Nordic, EBU)

- In decibels relative to Maximum Permitted Level (e.g. DIN, ABC, SABC)

- In decibels relative to 0 dBu (e.g. CBC)

- In decibels relative to 0 dBFS (e.g. IEC 60268-18)

- In simple numerical marks which can be correlated with any of the above (e.g. British)

Whichever scheme is used, usually there is a scale mark corresponding to Alignment Level.

Most PPMs have an approximately logarithmic scale, i.e. roughly linear in decibels, to provide useful indications over a wide dynamic range.

Integration time

Tone burst

duration (ms)Under-indication Type I Type II 100 0 dB 10 −1 dB −2 dB 5 −2 dB −4 dB 3 −4 dB 1.5 −7 dB 0.5 −17 dB 0.4 −15 dB Quasi-PPMs have a short integration time in order to register peaks longer than a few milliseconds in duration. In the original context of AM radio broadcasting in the 1930s, overloads due to shorter peaks were considered unimportant on the grounds that the human ear could not detect distortion due to momentary clipping. Ignoring momentary clipping made it possible to increase average modulation levels. In modern digital audio practice, where quality standards are hopefully much higher than AM radio in the 1930s, clipping of even short peaks is usually regarded as something to avoid.

On typical, real-world audio signals, a quasi-PPM under-reads the true peak by 6 to 8 dB.[3] Nevertheless, quasi-PPMs are still widely used in the digital age because of their usefulness in achieving programme balance. Overloads are avoided by allowing, typically, 9 dB of 'headroom' when controlling digital levels with a quasi-PPM.

The extent to which quasi-PPMs show less than the true amplitude of momentary peaks is determined by the 'integration time'. This is defined by IEC 60268-10 as "the duration of a burst of sinusoidal voltage of 5000 Hz at reference level which results in an indication 2 dB below reference indication".[4][5] This standard also contains tables showing the difference between indicated and true peaks for tone bursts of other durations. The longer the integration time, the greater the difference between the true and indicated peaks.

In earlier standards, different methods of measurement and criteria were used, such as 0.2 Neper or 80% voltage instead of 2 dB, but the practical difference between them was small.[6]

A Type I PPM has an integration time of 5 milliseconds and a Type II PPM has an integration time of 10 milliseconds.

Return time

All PPMs have a return time which is much longer than the integration time, to give the operator more time to see the peaks and reduce eye strain. Type I PPMs fall back 20 dB in 1.7 seconds. Type II PPMs fall back 24 dB in 2.8 seconds.

History and national variants

The PPM was originally developed for use in AM radio broadcasting networks in the 1930s, independently in both Germany and the United Kingdom, as a superior alternative to earlier types of meter which were not much use for monitoring peak audio levels. These were both quasi-peak meters with some features in common but otherwise substantially different.

IEC 60268-10 Type I PPM

Germany

German 'lichtzeiger' instrument (Siemens & Halske 1950)

German 'lichtzeiger' instrument (Siemens & Halske 1950)

In about 1936 and 1937, German broadcasters developed a peak programme meter which used a mirror galvanometer known as a 'lichtzeiger' (light pointer) for the display. The system consisted of a drive amplifier (e.g. ARD types U21 and U71) and a separate display unit (e.g. ARD types J47 and J48).[7] A stereo version, known as a 'doppel lichtzeiger' contained two mirror galvanometer displays in a single housing. Such displays were still used until the 1970s, when solid-state bargraph displays became the norm.

The design became standardised as DIN 45406. It evolved into the Type I meter in IEC 60268-10 and it is still known colloquially as a DIN PPM. Compared to the Type II designs it has faster integration and return times, a much wider dynamic range and a scale which is semi-logarithmic and calibrated in dB relative to maximum level. It continues to be used in much of northern Europe.[8]

In German broadcasting, the nominal analogue signal corresponding to Maximum Permitted Level was standardised by ARD at 1.55 volts (+6 dBu), and this is the usual sensitivity of a DIN-type PPM for an indication of 0 dB. Alignment Level (−3 dBu) is shown on the meter by a scale mark at −9.

In Scandinavia a variant of the DIN PPM known as 'Nordic' is used. It has the same integration and return times but a different scale, with 'TEST' corresponding to Alignment Level (0 dBu) and +9 corresponding to Maximum Permitted Level (+9 dBu). [8][2][9] Compared to the DIN scale, the Nordic scale is more logarithmic and covers a somewhat smaller dynamic range.

IEC 60268-10 Type II PPM

United Kingdom

An old-style British PPM with right-hand mechanical zero, as used with valve equipment (switched off when photo taken).

An old-style British PPM with right-hand mechanical zero, as used with valve equipment (switched off when photo taken).

The BBC used a number of methods of measuring programme volume in its early years, including the 'volume indicator' and 'slide-back voltmeter'.

By 1932, when the BBC moved to purpose-built facilities in Broadcasting House, the first audio meter to be known as a 'programme meter' was introduced. It was developed by Charles Holt-Smith of the Research Department and became known as the 'Smith meter'. This was the first meter with white markings on a black background. It was driven by a circuit that gave a roughly logarithmic transfer characteristic, so it could be calibrated in decibels. The overall characteristics were the product of the driver circuit and the movement's ballistics.

The first of the PPMs was designed by C. G. Mayo, also of the BBC's Research Department. It came into service in 1938. It kept the Smith meter's logarithmic, white-on-black display, and included all the key design features that are still used to this day with only slight modification: full-wave rectification, fast integration and slow return times, and a simple scale calibrated from 1 to 7.

The integration and return times were determined after a series of experiments. At first it was intended to create a true peak meter to prevent transmitters from exceeding 100% modulation. A prototype meter was created with an integration time of about 1 ms. It was found that the ear is tolerant of distortion lasting a few ms, and that a 'registration time' of 4 ms would suffice. The return time had to be a compromise between a rapid return, which was tiring to the eye, and a slow return, which made control difficult. It was decided that the meter should take between 2s and 3s to drop back 26 dB.[10][11]

The BBC PPM became the subject of several formal standards: BS 4297:1968 (superseded); BS5428:Part 9:1981 (superseded) and then BS 6840-10:1991. The text of the latter is identical to the Type IIa PPM in IEC 60268-10:1991.[8]

Alignment level (0 dBu) and Maximum Permitted Level (+8 dBu) correspond to scale marks '4' and '6' respectively.

The BBC PPM was adopted by commercial broadcasters in the UK. Other organisations around the world, including the EBU, CBC and ABC used the same dynamics but with slightly different scales.[8]

Modern British PPMs have a 4 dB spacing between the scale marks. Older designs had a 6 dB spacing between '1' and '2'. This discrepancy can sometimes also be found at the equivalent position on the derived CBC and ABC scales.

From its inception in 1939 until 2009, the PPM display was available in the form of an electro-mechanical, moving-coil meter movement with a demanding ballistic specification. For many years these were manufactured by Ernest Turner and Company[10], and in later years by Sifam, based in Torquay. In 2009 Sifam announced it would end production of the Type 74 dual-needle meter movement. In 2010 this was followed by the end of all PPM meter movement manufacturing by Sifam. Three major users - Bryant Unlimited, Canford Audio and TSL - placed final orders with Sifam for large stocks of the meters to supply manufacturing and maintenance activities for several years.[12]

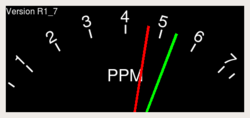

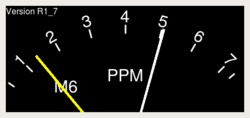

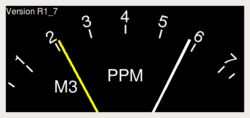

Stereo British PPMs

Stereo PPMs implemented in software: screenshots from BBC Research's open-source 'baptools' package.[13]In the UK, twin-needle PPMs are sometimes used for stereo. Red and green needles are used for left and right. This colour convention comes from port and starboard navigation lights, in accordance with an ancient BBC in-joke about Broadcasting House resembling a battleship. White and yellow needles are used for sum and difference (M and S). A more recent variation is to use a black needle with a dayglo orange tip for S instead of yellow.

The sensitivity of the S indication can be increased on some meter installations by 20 dB; this is to aid line-up procedures, e.g. of stereo mic pairs, or the azimuth of analogue tape machine heads, which rely on cancellation of the S signal.

M3 and M6

M and S needles are normally aligned so that M = L + R − 6 dB and S = L − R − 6 dB; this is known as the M6 standard. A signal, equal in amplitude and phase in the left and right channels will show the same meter deflection for M as it does for L and R.

M6 has largely replaced the earlier M3 standard in which the M and S needles indicated 3 dB higher. M3 was intended as a compromise to ensure mono compatibility when stereo programmes were listened to on mono receivers, which pick up only the M signal.

With M6, a widely-panned sound that peaked to its maximum 6 on, say, the left channel would peak only 4.5 on M. The same sound in the centre of the stereo image would peak 6 on M. This is a 6 dB variation for the mono listener.

With M0, i.e. simple M = L + R, a widely-panned sound peaking 6 would peak to 6 on M, but when panned centre would need to peak just 4.5 on each channel to keep M at 6. This is a 6 dB variation for the stereo listener.

With M3, any variations as sounds are panned are kept to 3 dB. Moreover, for most non-phase-coherent stereo sounds, the sum of the two channel voltages averages 3 dB (the full 6 dB sum is only achieved by exactly in-phase signals, i.e. a mono signal panned centre), so with M = L + R − 3 dB, most stereo sounds are a 'good fit' to the maximum permissible signal (PPM 6) on M, L and R.

M6, however, better reflects the absolute signal level and keeps the M needle at '4' for Alignment Level and '6' for peaks, without the operator having to remember to subtract 3 dB.

Commercial broadcasting in the UK initially used M3[14] but had switched to M6 by 1980. This was mandated by the IBA's Engineering Code of Practice.[15] BBC installations used M3 until 1999. The BBC now uses M6, but this has not been rolled out universally - many parts of the corporation still use 'traditional' M3.

European Broadcasting Union

The EBU PPM is a variant of the British PPM designed for the control of programme levels in international programme exchange. It is formalised as the Type IIb PPM in IEC 60268-10. It is identical to the British PPM except for the scale plate, which is calibrated in dB relative to Alignment Level, which is marked 'TEST'. There are also ticks at 2 dB intervals and at +9 dB, corresponding to Maximum Permitted Level.

USA

In the late 1930s PPMs were considered for use in the USA, but rejected in favour of a 'Standard Volume Indicator' (VU meter) on grounds of cost. Joint research by CBS, NBC and Bell Labs found that using an experimental design of PPM (with a relatively long integration time of 25 ms) in the control of programme levels gave only a 1 dB advantage over the VU meter, in terms of average output level for a given amount of distortion. It was felt that this was too small to justify the much greater expense. It was also found that VU meters gave more consistent readings than PPMs when comparing programme levels at the sending and receiving end of long lines subject to group delay, which altered the waveform.[16] This finding has been disputed by others.[17]

A widely-believed myth is that the PPM was developed as a superior alternative to the VU meter. In fact, the PPM came first, and if anything the VU meter was developed as an economical alternative to the PPM.[16]

By 1980, ABC had about 100 PPMs in use in control rooms in New York and its Washington News Bureau, and was ordering new consoles with PPMs fitted. These were Type II PPMs with the seven marks labelled −22, −16, −12, −8, −4, 0 and +4. ABC found a modified version of the EBU meter based on the VU-meter 'A scale' to be the best since it let operators use their usual jargon such as 'zero level' etc.[17] The appearance is similar to an EBU scale except that the numbers are 8 dB lower.

To aid alignment on both VU meters and PPMS, ABC in New York used a special test signal known as ATS. A 440 Hz tone alternated between steady tone at +8 dBu (indicated at 0 VU and −8 PPM) and tone bursts at +16 dBu (indicated at 0 VU and 0 PPM).[17]

Canada

By 1978 PPMs were in use at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Vancouver plant. Some 30 or 40 PPMs were in use, with just one or two VU meters retained for settling telco disputes. These are Type II PPMs with the seven marks labelled −6, 0, +4, +8, +12, +16 and +20: this scaling shows absolute levels in dBu (or dBm into 600

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

Peak Programme Meter — Ein Aussteuerungsmesser (auch: Pegelmesser) ist ein Anzeigeinstrument zur Kontrolle der Aussteuerung bei Tonaufnahmen. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Technische Eigenschaften 1.1 Bauarten 1.1.1 Spitzenpegelmesser 1.1.2 Gleichrichtwert Pegelmesser … Deutsch Wikipedia

Peak Programme Meter — PPM, échelle audio numérique (IEC 268 18). Un peak programme meter (PPM) est un Instrument de mesure utilisé par les professionnels du son pour indiquer le niveau d un signal audio. Sommaire 1 … Wikipédia en Français

Peak Program Meter — Ein Aussteuerungsmesser (auch: Pegelmesser) ist ein Anzeigeinstrument zur Kontrolle der Aussteuerung bei Tonaufnahmen. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Technische Eigenschaften 1.1 Bauarten 1.1.1 Spitzenpegelmesser 1.1.2 Gleichrichtwert Pegelmesser … Deutsch Wikipedia

Programme level — refers to the level that an audio source is transmitted or recorded at, and is important in audio if listeners to CD s, radio and television are to get the best experience, without excessive noise in quiet periods or compression of loud sounds.… … Wikipedia

Peak meter — A peak meter is a type of visual measuring instrument that indicates the instantaneous level of an audio signal that is passing through it (a sound level meter). In sound reproduction, the meter, whether peak or not, is usually meant to… … Wikipedia

VU meter — A VU meter is often included in analog audio equipment to display a signal level in Volume Units.It is intentionally a slow measurement, averaging out peaks and troughs of short duration to reflect the perceived loudness of the material. It was… … Wikipedia

Quasi-peak — means not quite peak , or aiming towards peak but not actually peak . The term is commonly used when referring to electronic detectors or rectifiers. Despite the above definition, the term quasi peak should not be interpreted as vague in any way … Wikipedia

vu-Meter — Analoges vu Meter Ein vu Meter[1] (auch: vu Messer oder vu Messgerät, vu steht dabei für englisch volume units, also in etwa „Lautstärkeneinheiten“) ist ein Messinstrument zur Beurteilung der Aussteuerung in der Tontechnik. Während sich die… … Deutsch Wikipedia

VU-Meter — Ein VU Meter (englisch, so viel wie VU Messer oder VU Messgerät) ist ein Anzeigeinstrument zur Beurteilung der Aussteuerung in der Tontechnik. VU steht hierbei für Volume Unit. Auf englisch ist es ein volume indicator instrument (VI). Analoges VU … Deutsch Wikipedia

VU Meter — Ein VU Meter (englisch, so viel wie VU Messer oder VU Messgerät) ist ein Anzeigeinstrument zur Beurteilung der Aussteuerung in der Tontechnik. VU steht hierbei für Volume Unit. Auf englisch ist es ein volume indicator instrument (VI). Analoges VU … Deutsch Wikipedia