- Enrico Dandolo

-

For the 19th century Risorgimento fighter, see Enrico Dandolo (patriot).

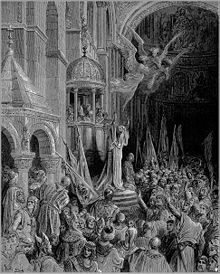

Dandolo Preaching the Crusade by Gustave Doré

Dandolo Preaching the Crusade by Gustave Doré

Enrico Dandolo (1107? – 21 June 1205) — anglicised as Henry Dandolo and Latinized as Henricus Dandulus — was the 41st Doge of Venice from 1195 until his death. Remembered for his blindness, piety, longevity, and shrewdness, and is infamous for his role in the Fourth Crusade which he, at age ninety and blind, surreptitiously redirected against the Byzantine Empire from reconquering the Holy Land, sacking Constantinople in the process.

In the nineteenth-century, the Regia Marina (Italian Navy) launched an ironclad battleship named Enrico Dandolo.

Contents

Blindness

It is not known for certain when and how Dandolo became blind. The story passed around after the Fourth Crusade (which is the version told by modern Venetians and accepted by many historians) was that he had been blinded by the Byzantines during his 1171 embassy, although it is possible that he suffered from cortical blindness as a result of a severe blow to the back of the head received sometime between 1174 and 1176.[1]

Dandolo's blindness appears to have been total. Writing thirty years later, Geoffrey de Villehardouin, who had known Dandolo personally, stated, "Although his eyes appeared normal, he could not see a hand in front of his face, having lost his sight after a head wound." Although even this account may have become exaggerated by the gloss of time, it is clear in any event that Dandolo's sight was severely impaired.

Life

Early career in politics

Born in Venice, he was the son of the powerful jurist and member of the ducal court, Vitale Dandolo. Dandolo had served the Serenissima Republic in diplomatic (as ambassador to Ferrara and bailus in Constantinople) and perhaps military roles for many years.

Dandolo was from a socially and politically prominent Venetian family. His father Vitale was a close advisor of Doge Vitale II Michiel, while an uncle, also named Enrico Dandolo, was patriarch of Grado, the highest-ranking churchman in Venice. Both these men lived to be quite old, and the younger Enrico was overshadowed until he was in his sixties.

Dandolo's first important political roles were during the crisis years of 1171 and 1172. In March 1171 the Byzantine government had seized the goods of thousands of Venetians living in the empire, and then imprisoned them all. Popular demand forced the doge to gather a retaliatory expedition, which however fell apart when struck by the plague early in 1172. Dandolo had accompanied the disastrous expedition against Constantinople led by Doge Vitale Michiel during 1171-1172. Upon returning to Venice, Michiel was killed by an irate mob, but Dandolo escaped blame and was appointed as an ambassador to Constantinople in the following year, as Venice sought unsuccessfully to arrive at a diplomatic settlement of its disputes with Byzantium. Renewed negotiations begun twelve years later finally led to a treaty in 1186, but the earlier episodes seem to have created in Enrico Dandolo a deep and abiding hatred for the Byzantines.

During the following years Dandolo twice went as ambassador to King William II of Sicily, and then in 1183 returned to Constantinople to negotiate the restoration of the Venetian quarter in the city.

Dogeship

On 1 January 1193, Dandolo became the thirty-ninth Doge of Venice. Already old and blind, but deeply ambitious, he displayed tremendous mental and (for his age) physical strength. Some accounts say he was already 85 years old when he became Doge. His remarkable deeds over the next eleven years bring that age into question, however. Others have hypothesized that he may have been in his mid-70s when he became Venice's leader.

Two years after taking office, in 1194, Enrico enacted reforms to the Venetian currency system. He introduced the large silver grosso worth 26 denarii, and the quartarolo worth 1/4 of a dinaro. Also he reinstated the Bianco worth 1/2 denaro, which had not been minted for twenty years. He debased the dinaro and its fractions, whereas the grosso was kept at 98.5% pure silver to ensure its usefulness for foreign trade. Enrico's revolutionary changes made the grosso the dominant currency for trade in the Mediterranean and contributed to the wealth and prestige of Venice. In later years, the value of the grosso would climb relative to the increasingly debased denaro, until it was itself debased in 1332. Soon after the introduction of the grosso, the dinaro began to be referred to as the piccolo. Literally grosso means "large one" and piccolo means "small one".

Fourth Crusade

In 1202 the knights of the Fourth Crusade were stranded in Venice, unable to pay for the ships they had commissioned after far fewer troops arrived than expected. Dandolo developed a plan that allowed the crusaders' debt to be suspended if they assisted the Venetians in restoring nearby Zadar to Venetian control. At an emotional and rousing ceremony in San Marco di Venezia, Dandolo "took the cross" (committed himself to crusading) and was soon joined by thousands of other Venetians. Dandolo became an important leader of the crusade.

Venice was the major financial backer of the Fourth Crusade, supplied the Crusaders' ships, and lent money to the Crusaders who became heavily indebted to Venice. Because of the crusaders' continued delays, provisions were also a problem for the enterprise.

Although they were supposed to be sailing to Egypt, Dandolo convinced them to stop at Zadar, a port city on the Adriatic that was claimed both by Venice and by the Kingdom of Hungary. Dandolo encouraged the crusaders to attack the city which had rebelled from Venice. A small number of Crusaders refused to help; but the others realized that the conquest of the rebel town and subsequent wintering there was the only way to hold the faltering crusade together. Zadar was besieged and captured on November 15, 1202.

Shortly afterwards, Alexius Angelus, son of the deposed Byzantine emperor Isaac II, arrived in that city. Dandolo agreed to go along with the crusade leaders' plan to place Alexius Angelus on the throne of the Byzantine Empire in return for Byzantine support of the crusade. This ultimately led to the conquest and sack of Constantinople on April 13, 1204, an event at which Dandolo was present and in which he played a directing role. The Catholic Crusaders then took permanent control of the Eastern Orthodox capital of Constantinople and established a Catholic state, the Latin Empire. In the Partitio Romaniae, Venice gained title to three-eighths of the Byzantine Empire as a result of her crucial support to the Crusade. The Byzantine Empire was never again as powerful as it had been prior to the Fourth Crusade.

Nineteenth-century grave marker in the Hagia Sophia's East Gallery

Nineteenth-century grave marker in the Hagia Sophia's East Gallery

He was active enough to take part in an expedition against the Bulgarians, but died in 1205. He was buried in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, probably in the upper Eastern gallery. In the 19th century an Italian restoration team placed a cenotaph marker near the probable location, which is still visible today. The marker is frequently mistaken by tourists as being a medieval marker of the actual tomb of the doge. The real tomb was destroyed by the Turks after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 and subsequent conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.[citation needed]

Descendants

His son, Raniero, served as vice-doge during Dandolo's absence and was later killed in the war against Genoa for the control of Crete. His granddaughter, Anna Dandolo, was married to the Serbian king Stefan Nemanjić. Although later genealogists attributed a whole brood of distinguished children to the doge, none of them actually existed. It is very possible that he had only the one son. During his dogeship he was married to a woman named Contessa, who may have been a member of the Minotto clan. Although there were several subsequent doges of the Dandolo family, none were direct descendents of Enrico.

Notes

- ^ Madden 2003

References

- Madden, Thomas F. (1993). "Venice and Constantinople in 1171 and 1172: Enrico Dandolo's Attitude towards Byzantium". Mediterranean Historical Review 8 (2): 166–185. doi:10.1080/09518969308569655.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2003). Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7317-7.

- Robbert, Louise Buenger (1974). "Reorganization of the Venetian Coinage by Doge Enrico Dandolo". Speculum, Vol. 49, No. 1 (Speculum, Vol. 49, No. 1) 49 (1): 48–60. doi:10.2307/2856551. JSTOR 2856551.

- Stahl, Alan M (2000). Zecca the mint of Venice in the Middle Ages. American Numismatic Society.; NetLibrary, Inc.. ISBN 080187694X. 9780801876943.

Preceded by

Orio MastropieroDoge of Venice

1192–1205Succeeded by

Pietro ZianiCategories:- 1100s births

- 1205 deaths

- People from Venice (city)

- Doges of Venice

- 13th century in the Byzantine Empire

- Christians of the Fourth Crusade

- 12th-century Italian people

- 13th-century Italian people

- House of Dandolo

- 12th-century rulers in Europe

- 13th-century rulers in Europe

- Blind people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.