- Anagnorisis

-

Anagnorisis (

/ˌænəɡˈnɒrɨsɨs/; Ancient Greek: ἀναγνώρισις) is a moment in a play or other work when a character makes a critical discovery. Anagnorisis originally meant recognition in its Greek context, not only of a person but also of what that person stood for. It was the hero's sudden awareness of a real situation, the realisation of things as they stood, and finally, the hero's insight into a relationship with an often antagonistic character in Aristotelian tragedy.[1]

/ˌænəɡˈnɒrɨsɨs/; Ancient Greek: ἀναγνώρισις) is a moment in a play or other work when a character makes a critical discovery. Anagnorisis originally meant recognition in its Greek context, not only of a person but also of what that person stood for. It was the hero's sudden awareness of a real situation, the realisation of things as they stood, and finally, the hero's insight into a relationship with an often antagonistic character in Aristotelian tragedy.[1]Contents

Tragedy

"Lear and Cordelia" by Ford Madox Brown: Lear, driven out by his older daughter and rescued by his youngest, realizes their true characters.

"Lear and Cordelia" by Ford Madox Brown: Lear, driven out by his older daughter and rescued by his youngest, realizes their true characters.

In the Aristotelian definition of tragedy, it was the discovery of one's own identity or true character (e.g. Cordelia, Edgar, Edmund, etc. in Shakespeare's King Lear) or of someone else's identity or true nature (e.g. Lear's children, Gloucester's children) by the tragic hero. In his Poetics, Aristotle defined anagnorisis as "a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune" (Part II: Section A.3:d. Recognition).

Shakespeare did not base his works on Aristotelian theory of tragedy, including use of hamartia, yet his tragic characters still commonly undergo anagnorisis as a result of their struggles.[citation needed].

Aristotle was the first writer to discuss the uses of anagnorisis, with peripeteia caused by it. He considered it the mark of a superior tragedy, as when Oedipus killed his father and married his mother in ignorance, and later learned the truth, or when Iphigeneia in Tauris realizes in time that the strangers she is to sacrifice are her brother and his friend, and refrains from sacrificing them. Aristotle considered these complex plots superior to simple plots without anagnorisis or peripetia, such as when Medea resolves to kill her children, knowing they are her children, and does so.

Another prominent example of anagnorisis in tragedy is in Aeschylus's "The Choephoroi" ("Libation Bearers") when Electra recognizes her brother, Orestes, after he has returned to Argos from his exile, at the grave of their father, Agamemnon, who had been murdered at the hands of Clytemnestra, their mother. Electra convinces herself that Orestes is her brother with three pieces of evidence: a lock of Orestes's hair on the grave, his footprints next to the grave, and a piece of weaving which she embroidered herself. The footprints and the hair are identical to her own. Electra's awareness of her brother's presence, who is the one person who can help her by avenging the death of their father.[2]

Comedy

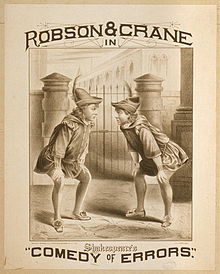

Poster for a performance of The Comedy of Errors: When the twins, confused with each other throughout the play, recognize each other's existence, the play reaches its happy ending.

Poster for a performance of The Comedy of Errors: When the twins, confused with each other throughout the play, recognize each other's existence, the play reaches its happy ending.

The section of Aristotle's Poetics dealing with comedy did not survive, but many critics also discuss recognition in comedies. A standard plot of the New Comedy was the final revelation, by birth tokens, that the heroine was of respectable birth and so suitable for the hero to marry. This was often brought about by the machinations of the tricky slave. This plot appears in Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, where a recognition scene in the final act reveals that Perdita is a king's daughter rather than a shepherdess, and so suitable for her prince lover.[3]

Mystery

The earliest use of anagnorisis in a murder mystery was in "The Three Apples", a classical Arabian Nights tale, where the device is employed to great effect in its twist ending.[4] The protagonist of the story, Ja'far ibn Yahya, is ordered by Harun al-Rashid to find the culprit behind a murder mystery within three days or else be executed. It is only after the deadline has passed, and as he prepares to be executed, that he discovers that the culprit was his own slave all along.[5][6]

Anagnorisis, however, is not limited to classical or Elizabethan sources. Author and lecturer Ivan Pintor Iranzo points out that contemporary auteur M. Night Shyamalan uses similar revelations in The Sixth Sense, in which child psychologist Malcolm Crowe successfully treats a child who is having visions of dead people, only to realize at the close of the film that Crowe himself is dead, as well as in Unbreakable, in which the character of David realizes that he survived a train crash that killed the other passengers, due to a supernatural power.[7]

See also

References

- ^ Northrop Frye, "Myth, Fiction, And Displacement" p 25 Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology, ISBN 0-15-629730-2

- ^ Aeschylus, and Robert Lowell. The Oresteia of Aeschylus. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1978.

- ^ Northrop Frye, "Recognition in The Winter's Tale" p 108-9 Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology, ISBN 0-15-629730-2

- ^ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Tale_of_the_Three_Apples

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 95–6, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, pp. 241–2, ISBN 0814332595

- ^ Ivan Pintor Iranzo. The naked and the dead. The Representation of the dead and the construction of the other in contemporary cinema: The case of M. Night Shyamalan, No. 4, 2005

Categories:- Ancient Greek theatre

- Literary concepts

- Narratology

- Plot (narrative)

- Poetics

- Greek loanwords

- Fiction

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.