- Hellbender

-

Hellbender

Head is in lower right corner Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Subphylum: Vertebrata Class: Amphibia Subclass: Lissamphibia Order: Caudata Family: Cryptobranchidae Genus: Cryptobranchus Species: C. alleganiensis Binomial name Cryptobranchus alleganiensis

(Daudin, 1803)Subspecies C. a. alleganiensis (Eastern Hellbender)

C. a. bishopi (Ozark Hellbender)

The distribution of the Eastern Hellbender (Ozark Hellbender is not indicated) The hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), also known as the hellbender salamander, is a species of giant salamander that is endemic to eastern North America.[1] A member of the Cryptobranchidae family, Hellbenders are the only members of the Cryptobranchus genus, and are joined only by one other genus of salamanders (Andrias, which contains the Japanese and Chinese Giant Salamanders) at the family level.[2] Hellbenders are ecologically significant for many reasons, including their uniqueness. These salamanders are much larger than any others in their endemic range, they employ an “unusual” means of respiration (which involves cutaneous gas exchange through capillaries found in their dorsoventral folds), and they fill a particular niche—both as a predator and prey—in their ecosystem which either they or their ancestors have occupied for around 65 million years.[2][3]

Contents

Etymology

The origin of the name "hellbender" is unclear. The Missouri Department of Conservation says:

The name 'hellbender' probably comes from the animal’s odd look. Perhaps it was named by settlers who thought "it was a creature from hell where it’s bent on returning". Another rendition says the undulating skin of a hellbender reminded observers of 'horrible tortures of the infernal regions'. In reality, it’s a harmless aquatic salamander.[4]

Vernacular names include "snot otter", "devil dog", "mud-devil", "grampus", "Allegheny alligator", "mud dog", and "leverian water newt".[5][6] The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek, "kryptos" (hidden[7]) and "branchos" (gill); a reference to oxygen absorption primarily through gills that are in a covered chamber and not lungs.[8]

Diagnosis

The Hellbender has a few characteristics that make it distinguishable from other native salamanders—these include a gigantic, dorsoventrally flattened body with thick folds travelling down the sides, a single open gill slit on each side, and hind feet that have five toes each.[2][9] Easily distinguished from most other endemic salamander species simply by their size—Hellbenders average up to sixty centimeters or about two feet in length—the only species that requires further distinction (due to an overlap in distribution and size range) is the mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus).[10][11] This demarcation can be made by noting the presence of external gills in the mudpuppy, which are lacking in the Hellbender, as well as by noting the presence of four toes on each hind foot of the mudpuppy (in contrast with the Hellbender’s five).[2] Furthermore, the average size of C. a. alleganiensis has been reported to be 45-60 cm (with some being reported as reaching up to 74 cm --30"), while N. m. maculosus has a reported average size of 28-40 cm in length, which means that Hellbender adults will still generally be notably larger than even the biggest Mudpuppies. [10][12][3]

Taxonomy

As was already mentioned, Hellbenders are members of the Cryptobranchidae family. This family is divided into two groups: the genus Cryptobranchus, and the genus Andrias (which contains the Chinese and Japanese Giant Salamanders, the two largest species of salamanders in the world).[11]

The genus Cryptobranchus has historically only been considered to contain one species, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, with two subspecies, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis and Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi. [6] Recent decline in population size of the Ozark subspecies Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi has led to further research into populations of this subspecies, including genetic analysis to determine the best route for conservation status.[10] Crowhurst et al., for instance, found that the “Ozark subspecies” denomination is insufficient for describing genetic (and therefore evolutionary) divergence within the Cryptobranchus genus in the Ozark region. The researchers found three equally divergent genetic units within the genus: Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis, and two distinct eastern and western populations of Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi. These three groups were shown to be isolated and are considered to most likely be “diverging on different evolutionary paths".[10]

Physical description

Hellbenders exhibit no sexual dimorphism, except during the fall mating season when males have a bulging ring around the cloaca. Both males and females grow to an adult length of 24 centimetres (9.4 in) to 40 centimetres (16 in) from snout to vent, with a total length of 30 centimetres (12 in) to 74 centimetres (29 in) making it the third largest aquatic salamander species in the world (next to the Chinese Giant Salamander and the Japanese Giant Salamander) and the largest in North America.[11] An adult weighs 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb) to 2.5 kilograms (5.5 lb). Hellbenders reach sexual maturity at about five years of age, and may live thirty years in captivity.[13]

C. alleganiensis have flat bodies and heads, with beady dorsal eyes and slimy skin. Like most salamanders, they have short legs with four toes on the front legs and five on their back appendages, and their tails are keeled to propel them through water. The hellbender has working lungs, but gill slits are often retained although only immature specimens have true gills; the hellbender absorbs oxygen from the water through capillaries of its side-frills.[13] They are blotchy brown or red-brown in color, with a paler underbelly.

Distribution

Hellbender species are present in a number of eastern states that stretch “from southern New York to northern Georgia,”[14] including parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, and even a small bit of Oklahoma and Kansas.[1] The subspecies (or species, depending on the source) Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi is confined to the Ozarks of Northern Arkansas and Southern Missouri while Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis is found in the rest of the aforementioned states.[1]

Some Hellbender populations—namely a couple in Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—have historically been noted to be quite abundant, but several anthropogenic maladies have converged on the species such that is has seen serious population decline throughout its range. Hellbender populations were listed in 1981 as already extinct or endangered in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Maryland, decreasing in Arkansas and Kentucky, and were noted as being generally threatened as a species throughout their range by various human activities and developments.[1]

Ecology

The Hellbender salamander is considered to be a “habitat specialist”—in other words, it has adapted to fill a specific niche within a very specific environment. It is labeled as such “because its success is dependent on a constancy of dissolved oxygen, temperature and flow found in swift water areas,” which in turn limits it to a narrow spectrum of stream/river choices.[14] As a result of this specialism, Hellbenders are generally found in areas with large, irregularly shaped and intermittent rocks and swiftly moving water, and tend to avoid wider, slow moving waters with muddy banks and/or slab rock bottoms. This specialism likely aided the decline in Hellbender populations, as collecting was made easier by being able to easily spot their specific habitat selection.[14] One collector noted that before in the ecosystems natural condition, “one could find a specimen under almost every suitable rock,” but that after years of collecting, the population had declined significantly.[15] The same collector noted that he “never found two specimens under the same rock,” corroborating the account given by other researchers that Hellbenders are generally solitary—they are only thought to gather during the mating season.[15][16]

Both species, C. a. alleganiensis and C. a. bishopi undergo a metamorphosis after around a year and a half of life.[14] It is at this point—when they are roughly 13.5 centimeters in length—that they lose the gills that were present during their larval stage, and develop toes from lobes on their front limbs and “paddle-shaped” hind limbs. Until this point, they are easily confused with Mudpuppies, and can be differentiated often only through toe number.[13] After this metamorphosis, Hellbenders have to be able to absorb oxygen through the folds in their skin, which is largely behind the need for fast moving, oxygenated water. If a Hellbender ends up in an area of slowly moving water, not enough water will pass over its skin in a given time period, making it difficult to garner enough oxygen to support necessary respiratory functions. Likewise, a below favorable oxygen content can make life just as difficult.[15] Hellbenders are preyed upon by multiple different predators, including various fish and reptiles (including both snakes and turtles). Cannibalism of eggs is also considered to be a common occurrence.[11]

Life History and Behavior

Behavior

Once a Hellbender finds a favorable location, it generally does not stray too far from it—except occasionally for breeding and hunting—and will protect it from other Hellbenders both in and out of the breeding season.[16] While the range of two Hellbenders may overlap, they are noted as rarely being present in the overlapping area when the other salamander is in the area. The same researchers claim that the species is at least somewhat nocturnal, with peak activity being reported by one source as occurring around “two hours after dark” and again at dawn (although the dawn peak was recorded in the lab and could be misleading as a result).[16][13] Nocturnal activity has been found by at least one set of researchers to be most prevalent in early summer, perhaps coinciding with highest water depths.

Diet

Studies have been performed in which Hellbenders were captured, transported back to the lab, and then dissected to determine dietary habits. Stomach pumping of living specimens has also been performed to determine diet. These studies demonstrated quite clearly that C. alleganiensis feeds primarily on crayfish and small fish. One report, written by a commercial collector in the 1940s, noted a trend of more crayfish predation in the summer during times of higher prey activity, whereas fish made up a larger part of the winter diet while crayfish are less active.[15] There seems to be a specific temperature range in which Hellbenders feed as well: between 45 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Several researcher note that cannibalism—mainly on eggs—has been known to occur within Hellbender populations, and one researcher claims that perhaps density is maintained—and density dependence in turn created—in part by intraspecific predation.[16][14][13]

Reproduction

The hellbenders' breeding season begins in late August or early- to mid-September and can continue as late as the end of November, depending on region. During this time the male develops swollen cloacal glands. Unlike most salamanders, the hellbender performs external fertilization. Before mating, each male excavates a brood site, a saucer-shaped depression under a rock or log with its entrance positioned out of the direct current, usually pointing downstream. The male remains in the brood site awaiting a female. When a female approaches, the male guides or drives her into his burrow and prevents her from leaving until she oviposits.[13]

Female hellbenders lay 150-200 eggs over a 2- to 3-day period; the eggs are 18–20 mm in diameter, connected by 5–10 mm cords. As the female lays eggs the male positions himself alongside or slightly above them, spraying the eggs with seminal fluid while swaying his tail and moving his hind limbs, which disperses the sperm uniformly. The male often tempts other females to lay eggs in his nest, and as many as 1,946[17] eggs have been counted in a single nest. Cannibalism, however, leads to a much lower number of eggs in hellbender nests than would be predicted by ovarian counts.[13]

After oviposition the male drives the female away from the nest and guards the eggs. Incubating males rock back and forth and undulate their lateral skin folds, which circulates the water, increasing oxygen supply to both eggs and adult. Incubation lasts from 45–75 days, depending on region.[13] Hatchling hellbenders are 25 millimetres (0.98 in) to 33 millimetres (1.3 in) long, have a yolk sac as a source of energy for the first few months of life, and lack functional limbs.[13]

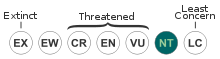

Conservation status

Research throughout the range of the hellbender has shown a dramatic decline in population abundance in the majority of locations. Many different anthropogenic sources have helped to create this decline, including the siltation and sedimentation, blocking of dispersal/migration routes, and destruction of riverine habitats that is created by dams and other development, as well as pollution, disease and over harvesting for commercial and scientific purposes.[1][3] As many of these detrimental effects have done irreversible damage to hellbender populations, it is important to conserve the remaining intact populations through protecting habitats and—perhaps in places where the species was once endemic and has been extirpated—by augmenting numbers through reintroduction.[1] Due to sharp decreases that have been seen in the Ozark subspecies, researchers have been looking at trying to differentiate C. a. alleganiensis and C. a. bishopi into two management units. Indeed, researchers found significant genetic divergence between the two groups, as well as between them and another isolated population of C. a. alleganiensis. This could be reason enough to ensure that work is done on both denominations, as preserving extant genetic diversity is of crucial Ecological importance.[1]

The Ozark hellbender has been listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Oct. 5, 2011. This hellbender subspecies inhabits the White River and Spring River systems in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas and its population has declined an estimated 75 percent since the 1980s, with only about 590 individuals remaining in the wild. Degraded water quality, habitat loss resulting from impoundments, ore and gravel mining, sedimentation, and collection for the pet trade are thought to be the main factors resulting in the amphibian's decline.[18]

Fossil record

Extant species in the Cryptobranchidae family are the modern-day members of a lineage that extends back millions of years—the earliest fossil records of a basal species date back to the Middle Jurassic and were found in volcanic deposits in Northern China.[19] (This reported estimated Middle Jurassic age for the fossils has been reputed and defended multiple times, and the debate is still not fully settled).[12] These specimens are the earliest known relatives of modern salamanders, and together with the numerous other basal groups of salamanders that are found in the Asian fossil record they form a concrete base of evidence for the fact that “the early diversification of salamanders was well underway” in Asia during the Jurassic period.[19] Interestingly, little has changed in the morphology of the Cryptobranchidae since the time of these fossils, leaving researchers to note that “extant Cryptobranchid salamanders can be regarded as living fossils whose structures have remained little changed for over 160 million years.”[19]

As the fossil record for the Cryptobranchidae shows an Asian origin for the family, the story of how these salamanders made it to the Eastern U.S. has been a point of scientific interest. Research has led to a dispersal via land-bridge based theory, and scientists have gone on to note the waves of adaptive radiation that seem to have swept the Americas from the North to South.[19][15]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Williams, R.D., Gates, J.T., Hocutt, C.H, and G.J. Taylor. The Hellbender: A Nongame Species in Need of Management. Wildlife Society Bulletin. Vol. 9:2 (2010) pp.94-100

- ^ a b c Guimond, R.W.,and V.H. Hutchison. Aquatic Respiration: An Unusual Strategy in the Hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis (Daudin). Science, New Series. Vol. 182:4118 (1973) pp.1263-1265.

- ^ a b c Sabatino, S.J., and E.J. Routman. Phylogeography and conservation genetics of the hellbender salamander (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis). Conservation Genetics. (2009) Vol. 10 pp.1235-1246

- ^ The Hellbender[dead link]

- ^ Nickerson, M.A. and C.E. Mays. 1973. The hellbenders: North American giant salamanders. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in Biology and Geology 1, 106pp.

- ^ Silvia Geser and Peter Dollinger. "WAZA virtual zoo". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA). http://www.waza.org/virtualzoo/factsheet.php?id=402-003-002-001&view=Amphibia. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=crypt. Retrieved 2011-10-18.

- ^ http://mdc.mo.gov/documents/nathis/herpetol/amphibian/hellbend.pdf[dead link]

- ^ Gehlbach, Frederick R. Comments on the Study of Ohio Salamanders with Key to Their Identification. Journal of the Ohio Herpetological Society. (1960) Vol. 2:3 pp.40-45.

- ^ a b c d Crowhurst, R.S., Faries, K.M., Collantes, J., Briggler, J.T., Koppelman, J.B., and Lori S. Eggert. Genetic relationships of hellbenders in the Ozark highlands of Missouri and conservation implications for the Ozark subspecies (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi). Conservation Genetics. (2010)

- ^ a b c d AmphibiaWeb - Cryptobranchus alleganiensis

- ^ Lanza, B., Vanni, S., & Nistri, A. (1998). Cogger, H.G. & R.G. Zweigel ed. Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 70–74

- ^ a b c d e f g h i http://www.fws.gov/midwest/eco_serv/soc/amphibians/eahe-sa.pdf Mayasich, J., Grandmaison, D., and Phillips, C. Eastern Hellbender Status Assessment Report.

- ^ a b c d e Peterson, C.L, Metter, D.E., Miller, B.T., Wilkinson, R.F., and M.S. Topping. Demography of the Hellbender Cryptobranchus alleganiensis in the Ozarks. American Midland Naturalist. (1988) Vol. 199:2 pp.291-303.

- ^ a b c d Swanson, P.L. Notes on the Amphibians of Venango County, Pennsylvania. American Midland Naturalist. (1948) Vol. 40:2 pp.362-371.

- ^ a b c d Humphries, W.J., and T.K. Pauley. Seasonal Changes in Nocturnal Activity of the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis, in West Virginia. Journal of Herpetology. (2000) Vol. 34:4 pp.604-607.

- ^ Chris Mattison (2005). Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. The Brown Reference Group. p. 23.

- ^ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lists the Ozark Hellbender as Endangered and Moves to Include Hellbenders in Appendix III of CITES" (Press release). U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011-10-05. http://us.vocuspr.com/Newsroom/Query.aspx?SiteName=fws&Entity=PRAsset&SF_PRAsset_PRAssetID_EQ=128569&XSL=PressRelease&Cache=True. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ a b c d Gao, K., and N.H. Shubin. Earliest known crown-group salamanders. Nature. (2003) Vol. 422 pp.424-428.

References

- Hammerson & Phillips (2004). Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 11 May 2006. Database entry includes a range map and justification for why this species is threatened.

- Petranka, James W. (1998) Salamanders of the United States and Canada, Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

External links

- Cryptobranchus alleganiensis on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species at International Union for Conservation of Nature

- Cryptobranchid Interest Group

- Eastern hellbender information at Commonwealth of Virginia

- Eastern Hellbender Fact Sheet at New York State

- Ozark Hellbender at U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

- Amiphibiaweb Entry for the Hellbender

- Cryptobranchus at CalPhotos

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Cryptobranchidae

- Amphibians of the United States

- Monotypic amphibian genera

- Animals described in 1803

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.