- Rova of Antananarivo

-

The Rova of Antananarivo /ˈruːvə/ (Malagasy: Rovan'i Manjakamiadana [ˈruvən manˌdzakəmiˈadə̥nə]) is a royal palace complex in Madagascar that served as the home of the sovereigns of the Kingdom of Imerina in the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as the rulers of the Kingdom of Madagascar in the 19th century. Located in the central highland city of Antananarivo, the Rova occupies the highest point on Analamanga, formerly the highest of Antananarivo's many hills. Merina king Andrianjaka, who ruled Imerina from around 1610 until 1630, is believed to have captured Analamanga from a Vazimba king around 1610 or 1625 and erected the site's first fortified royal structure. Successive Merina kings continued to rule from the site until the fall of the monarchy in 1896, frequently restoring, modifying or adding royal structures within the compound to suit their needs.

Over time, the number of buildings within the site varied. Andrianjaka founded the Rova with three buildings and a dedicated tomb site in the early 17th century. The number of structures rose to approximately twenty during the late 18th-century reign of King Andrianampoinimerina. By the late 20th century, the Rova's structures had been reduced to eleven, representing various architectural styles and historical periods. The largest and most prominent of these was Manjakamiadana, also known as the "Queen's Palace" after Queen Ranavalona I, for whom the original wooden palace was built between 1839–1841 by Frenchman Jean Laborde. In 1867 the palace was encased in stone for Queen Ranavalona II by Scotsman James Cameron, an artisan missionary of the London Missionary Society. The neighbouring Tranovola, a smaller wooden palace constructed in 1819 by Creole trader Louis Gros for King Radama I, was the first multi-storey building with verandas in the Rova. The model offered by Tranovola transformed architecture in the area over the course of the 19th century, inspiring a widespread shift toward two-storey houses with verandas. The Rova grounds also contained a cross-shaped wooden house (Manampisoa) built as the private residence of Queen Rasoherina, a stone Protestant chapel (Fiangonana), nine royal tombs, and a number of named wooden houses built in the traditional style reserved for the andriana (nobles) in Imerina. Among the most significant of these were Besakana, erected in the early 17th century by Andrianjaka and considered the throne of the kingdom, and Mahitsielafanjaka, a later building which came to represent the seat of ancestral spiritual authority at the Rova.

A fire on the night of 6 November 1995 destroyed or damaged all the structures within the Rova complex shortly before it was due to be inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Although officially declared an accident, rumours persist that politically motivated arson may have been the actual cause of the fire. The chapel and tombs, as well as Besakana and Mahitsielafanjaka, have since been fully restored with bilateral government donations, state funds and grants from intergovernmental and private donors. Reconstruction of the Manjakamiadana exterior is scheduled for completion in 2011, while interior restoration work will continue until at least 2013. Once the building is fully restored, Manjakamiadana will serve as a museum showcasing royal artefacts saved from destruction in the fire.

Contents

Background

Madagascar's central highlands were first inhabited between 200 BCE–300 CE by the island's earliest settlers, the Vazimba, who appear to have arrived by pirogue from southeastern Borneo and established simple villages in the island's dense forests.[1] By the 15th century the Merina ethnic group from the southeastern coast had gradually migrated into the central highlands[2] where they established hilltop villages interspersed among existing Vazimba settlements and ruled by local kings. In the mid-16th century these Merina villages—now fortified with stone walls, gateways and deep defensive trenches[3]—were united under the rule of King Andriamanelo (1540–1575), who initiated the first military campaigns to expel or assimilate the Vazimba population by force. Villages inhabited by the andriana (noble) class established by Andriamanelo[4] typically contained a rova or palace compound.[5]

The rova's earliest defining features had crystallised among the Merina as residences for local kings at least 100 years before the emergence of the united Kingdom of Imerina under Andriamanelo. According to custom, a rova's foundation was always elevated relative to the surrounding village. The compound also always featured a kianja (central courtyard) marked by a vatomasina (tall sacred stone) where the sovereign would stand to deliver kabary (royal speeches or decrees). Contained within the rova was at least one lapa (royal palace or residence) as well as the fasana (tomb) of one or more of the site's founders.[5] The sovereign's lodgings typically stood in the northern part of the rova, while the spouse or spouses lived in the southern part.[6] It was not until the dawn of the 19th century that a perimeter wall of sharpened wooden stakes would constitute another defining feature of rova construction.[5]

History

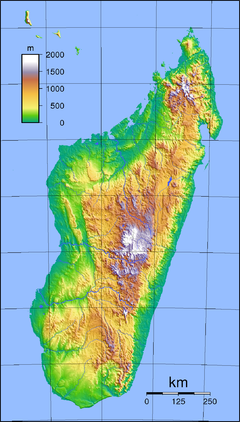

Location of the Rova of Antananarivo in Madagascar1610–1792

The Rova of Antananarivo is located 1,480 metres (4,860 ft) above sea level on Analamanga, originally the highest of the numerous hills in Antananarivo.[7] Around 1610[8] or 1625,[9] Andrianjaka, King of Imerina and grandson of King Andriamanelo, ordered a garrison of 1,000 soldiers to seize the strategic site from its original Vazimba inhabitants. He reportedly succeeded with minimal bloodshed. According to oral history, the mere encampment of his army at the foot of Analamanga was sufficient to secure the submission of the Vazimba.[10] Andrianjaka's army then cleared the forest covering the hill's summit and built a traditional rova to serve as an initial garrison, including an unnamed simple wooden house within it as a palace for the king. Soon afterward Andrianjaka built two more houses, reportedly named Masoandrotsiroa ("There Are Not Two Suns", also called Masoandro) and Besakana ("Great Breadth").[11] According to another account, Besakana may have been the name of the very first of the three houses Andrianjaka built within the Rova.[12] The king also designated the construction site and design for the royal tombs he named Trano Masina Fitomiandalana ("Seven Sacred Houses Arranged in Order", also called Fitomiandalana), which were to be laid out in a line.[13] Andrianjaka's own tomb was the first of these to be built.[14]

Generations of Andrianjaka's successors through to his great-grandson King Andriamasinavalona (1675–1710) ruled over the united central highland kingdom of Imerina from the Rova of Antananarivo. These monarchs occasionally altered the compound and its buildings to suit their purposes.[8] In particular, Besakana served as a primary royal residence and was repeatedly rebuilt, most notably for Andriamasinavalona who, according to oral history, had famously sought and then spared a human sacrifice in preparation for the endeavour.[12] At some point prior to 1800,[15] as the community of nobles inhabiting the Rova grew, the hilltop was lowered by 9.1 metres (30 ft) to expand the amount of level land available for construction. Consequently, among the hills of Antananarivo, the hilltop of Analamanga is now second in height to that of Ambohimitsimbina to the south.[16]

The role of the Rova as a seat of power for the Kingdom of Imerina changed when Andriamasinavalona chose to divide the kingdom into four provinces ruled by his favourite sons. Antananarivo became the capital of the southern Imerina province with the Rova as its seat of government. The site retained this role until the late 18th century, when King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810) of Ambohimanga led a series of attacks beginning in 1792 that culminated in the capture of Antananarivo and its reincorporation into the newly unified Kingdom of Imerina.[17]

1792–1810

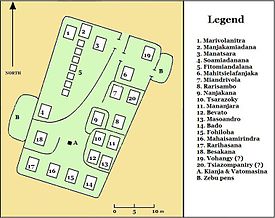

After Andrianampoinimerina reunited the divided and warring Kingdom of Imerina, he successfully pursued an expansionist policy that saw his authority extended over a large portion of Madagascar by the time of his death in 1810. Having captured Antananarivo by 1793[18] and transferred his capital from Ambohimanga to Antananarivo the following year,[19] Andrianampoinimerina established new structures on the Rova grounds that would become imbued with the political and historic significance of his reign. In keeping with the tradition of Merina sovereigns before him, each building was assigned a name by which it could be distinguished. Several of the buildings were used interchangeably by the king as personal residences, including Manjakamiadana ("Where It is Pleasant to Rule"),[20] Besakana, Manatsaralehibe ("Vast Improvement", also called Manatsara)—which he alone was authorised to enter—and Marivolanitra ("Beneath the Heavens"), a building reportedly designed with a staircase leading to a rooftop observation deck from which the king could observe the town and plains below.[21]

A number of the Rova's buildings possessed unique design features. The modest wood building then known as Manjakamiadana was also called Felatanambola ("Silver Hands") for the hand-shaped sculptures crafted from melted silver piastres and attached to each of the building's four tandrotrano (roof horns)—an architectural design element formed from the crossed gable beams that extended past the roof line of all traditional aristocratic Merina houses. Felatanambola's decorative silver hands were later affixed to the roof horns of Besakana. Another distinctive building from this period was called Bevato ("Many Stones") because its foundation was atypically composed of stone blocks.[22] Manatsara was said to be the most well constructed of the many houses because it was built using ambora (Tambourissa parrifolia), an extremely durable and rot-resistant indigenous hardwood, rather than a traditional wood called hazomena (Weinmannia rutenbergii).[23] According to oral history, Manatsara was treasured by Andrianampoinimerina and the house was quite old but still well preserved in the mid-19th century when Queen Ranavalona I decided to recover its interior walls with wood taken from Sihanaka country.[24]

Andrianampoinimerina's many wives and other family members occupied the majority of the buildings, most notably Mahitsielafanjaka ("That Which is Upright Rules Long", also called Mahitsy), the abode of wife Rabodonizimirabalahy, where the sampy (royal idol) called Manjakatsiroa was kept. Three other royal idols were kept on the Rova grounds, namely Rakelimalaza, Ramahavaly and Rafantaka, each of which were housed in their own separate buildings. Nanjakana ("Royal") was occupied by wives named Ramanantenasoa and Rasamona. Tsarazoky ("Good Eldest One") was the home of Ramiangaly,[21] while Rasendrasoa, Andrianampoinimerina's principal wife,[25] occupied Bado ("Stupid"). Rarihasana ("Armor of Sanctity") was inhabited by wives Ravaomanjaka and Razafinamboa; Andrianampoinimerina's son and heir, Radama I, would later offer this same house to Rasalimo, who eventually became one of Radama's wives. Three notable houses were inhabited by other family members. Andrianampoinimerina gave Besakana to his adopted daughter Ramavo (later to become Radama's wife and eventually Queen Ranavalona I). Andrianampoinimerina's sister, Ralaisoka, originally shared Besakana with Ramavo until a daughter named Ratsimanompo vacated a house called Fohiloha ("Short"), leaving Ralaisoka to occupy it alone. Masoandrotsiroa served as the residence of Ramavo's sister, Rangita, and an aunt named Rasalamo, a daughter of Andrianampoinimerina's grandfather King Andriambelomasina, was given a house named Rarisambo ("Fortified Ship").[21]

At least two buildings were transported in their entirety onto or away from the Rova compound during Andrianampoinimerina's reign. Miandrivola ("Guarding Money") was moved from Ambohidrano to the Rova compound, where it was inhabited by one of the king's wives, Rafaravavy.[21] The king also had Manatsara removed from Antananarivo to Ambohidrabiby.[24]

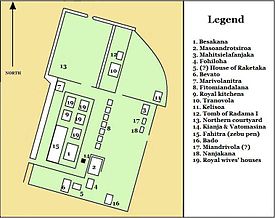

1810–1896

Following unification of the greater part of the island under Merina rule in the 19th century, the palaces of the Rova served as the seat of power for successive sovereigns of the Kingdom of Madagascar, including King Radama I (1810–1828), Queen Ranavalona I (1828–1861), King Radama II (1861–1863), Queen Rasoherina (1863–1868), Queen Ranavalona II (1868–1883) and lastly Queen Ranavalona III (1883–1895), who ruled from the Rova until Madagascar's annexation by France.[26] During his successful 1817 military campaign to pacify the east coast, Radama I—son and successor of Andrianampoinimerina—was favourably impressed by the houses he saw in Toamasina that had been built by newly arrived Creole merchants from Mauritius and Reunion.[27] Radama invited one of them, a craftsman named Louis Gros, to return with him to Antananarivo to redesign Bevato[28] as a home for his principal wife, Rasalimo. The new Bevato reportedly featured two stories, much like the houses Radama had seen in Toamasina.[6]

Another wooden palace, Tranovola ("Silver House"), was under construction at the same time as Bevato and is considered by historians to represent the first true hybrid of Creole and traditional Merina aristocratic architecture.[29] Its innovations included a roof of wood shingles,[27] a second storey, the addition of a veranda, glass windows, multiple interior rooms (as opposed to a single open interior space) and the use of curved shapes as design elements. Historic sources offer conflicting accounts of these two buildings. Some maintain that Bevato was relocated and remodelled to become Tranovola,[28] while others maintain the buildings were separate but debate which of the two houses was the first two-storey building in the Rova (still other sources award this innovation to Marivolanitra).[30] The design of Radama's tomb likewise embodies the hybrid style[31] that was to influence and inspire not only the majority of the buildings built at the Rova in the 19th century, but ultimately architecture throughout the entire highland region of Madagascar—particularly in its use of equidistant pillars supporting the overhanging roof to create a veranda.[29]

Despite the stylistic innovations Radama adopted for the construction of several of the compound's buildings, the Rova largely retained its traditional features during his reign. The basic layout of the compound remained largely unaltered from its original design with the sole exception of an expansion of the Rova along its north-south axis. Stone walls topped with sharpened wooden stakes were built around the new perimeter during this period. Venerable buildings such as Besakana, Nanjakana, Mahitsy and Manjakamiadana were retained, as were the houses of several of Andrianampoinimerina's wives, many of whom were still living at the time of Radama's death in 1828. During his reign, Radama undertook the restoration of Marivolanitra to serve chiefly as housing for visiting foreigners,[6] and briefly inhabited it himself[31] in addition to his main residence at Besakana. He also had a house called Kelisoa ("Petite Beauty") built as a lodging for his concubines.[6]

The Rova underwent several significant changes during the lengthy reign of Queen Ranavalona I. The largest of the buildings in the modern-day compound, the wooden Manjakamiadana, was built between 1839 and 1840.[32] Ranavalona also made further modifications to Tranovola in 1845, when it became the residence of her son Radama II. The boundaries of the compound were expanded to their largest and final extent, and numerous older buildings were removed from the Rova of Antananarivo to other towns in the highlands. Voahangy ("Pearl"), the former home of Andrianampoinimerina's wife Ramisa, was moved to Alasora. The house known as Tsiazompaniry ("Forbidden to be Desired"), formerly inhabited by another of his wives, Rabodonizimirahalahy, was moved to the region of Antanamalaza.[21] Bado was moved to Ambohidrabiby. The queen also moved Fohiloha, Kelisoa, Manatsara and Masoandro to the royal village of Ambohimanga.[24]

Later queens also left their mark on the Rova through major construction projects. Queen Rasoherina had Marivolanitra relocated to Mahazoarivo to make room for Manampisoa ("Adding What is Pleasant"), built from 1865 to 1867 for use as her personal residence. A Protestant chapel (Fiangonana) was erected during the reign of Ranavalona II, who also ordered the exterior of the wooden Manjakamiadana to be encased in stone. Plans to build a private residence for Ranavalona III were abandoned in 1896 at the time of French colonisation of the island.[33] According to one source, partial electrification of the Rova may have been successfully tested on Christmas Day 1892. Following this experiment, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony and Queen Ranavalona III began working with a contractor to purchase and install the necessary equipment to expand electrification throughout the Rova, but this initiative was also interrupted by the advent of French colonisation.[34]

1896–present

The 1896 French colonisation of Madagascar brought an end to the rule of the Merina sovereigns. The Rova of Antananarivo was converted into a museum the following year,[35] and the Fitomiandalana tombs were excavated and moved to a new location behind the tombs of Radama I and Rasoherina.[13] The bodies of sovereigns previously interred in the royal tombs at Ambohimanga were exhumed and transferred to the tombs in the Rova grounds, a sacrilegious move that degraded the status of Ambohimanga as a site of sacred pilgrimage. According to Frémigacci (1999), French colonial administrator General Joseph Gallieni undertook this desacralisation of the Rova in an attempt to break popular belief in the power of the royal ancestors. By the same token, his actions relegated Malagasy sovereignty under the Merina rulers to a relic of an unenlightened past and were a symbolic demonstration of the inferiority of Malagasy culture to that of the conquering French. The desecration of the two most sacred sites of Merina royalty represented a calculated political move intended to establish the political and cultural superiority of the colonial power.[35]

Following independence the Rova compound remained largely closed to the public throughout the First (1960–1972) and Second (1975–1992) Republics except on special occasions.[35] In 1995, three years into the Third Republic (1992–2010), the Rova compound was destroyed by fire.[36] The tombs, chapel, exterior of Manjakamiadina and two traditional wooden houses (Besakana and Mahitsy) have since been restored[37] with further restorations planned to continue until at least 2013.[38]

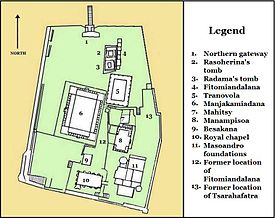

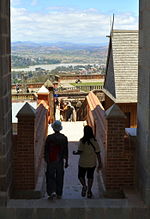

Buildings

The Rova compound extends to just less than one hectare (approximately two acres), spanning 116 metres (381 ft) north to south and over 61 metres (200 ft) from east to west.[16] A barricade of thick wooden posts with sharpened ends surrounded the compound until 1897 when it was replaced with a brick wall on the orders of General Gallieni. Entered via a stone stairway leading to a large north-facing gate built by James Cameron in 1845, this portal is topped by a bronze voromahery (eagle) imported from France by Jean Laborde in 1840.[39] Beyond the gate lies an open dirt courtyard approximately 37 metres (121 ft) square, with the far end opposite the gate delimited by the northern face and entrance of Manjakamiadana.[16] Over time, the Rova compound has contained several key buildings of political and historical significance, including five palaces, a chapel and nine tombs.[37]

Manjakamiadana

Manjakamiadana was built in two stages. The original palace, built between 1839 and 1840 on the orders of Ranavalona I, was built entirely in wood by Jean Laborde. In 1867, during the reign of Ranavalona II, a stone casing was erected around the original wooden structure.[35] The 30-metre (98 ft) long, 20-metre (66 ft) wide original wooden structure was 37 metres (121 ft) high, including the steeply pitched roof of wooden shingles, itself 15 metres (49 ft) in height. These measurements exclude the two superimposed balconies that extended 4.6 metres (15 ft) from the exterior walls and encircled the entire building, supported by 0.61-metre (2.0 ft) diameter wooden posts.[16] The exterior of the entire building, including the roof, was painted white, with the exception of the balcony railings which were red.[40] The exterior walls were composed of wooden planks tightly fitted together in a repeated chevron pattern reminiscent of traditional thatch walls, while the wood planks of the interior walls were hung vertically.[41] The building could be entered by three doors: the main entrance in the northern wall, another in the southern wall and a third reserved for servants in the eastern wall.[42]

An open and spacious ground floor respected the same traditional layout exemplified in Besakana and other Merina homes, including the presence of hearth stones in their customary corner.[22] Following traditional construction practices, the roof three stories above was supported by an enormous andry (central pillar) that was given the name Volamihitsy ("Genuine Silver").[41] According to popular legend, this was made of a single rosewood tree trunk transported from the eastern rain forests. Recent archaeological excavations of the site during reconstruction have since disproved this account as the pillar was found to be a composite of fitted rosewood pieces rather than a single solid post.[43] According to custom, the north-eastern corner pillar was the first to be erected. Its length necessitated the use of a pulley designed by Jean Laborde, the principal architect, to haul the trunk into place. When an accident occurred during the operation, the queen designated a Malagasy carpenter to manufacture a crane to complete the task. Thousands of the queen's subjects were forced to labour on the building's construction in lieu of paying cash taxes pursuant to a tradition called fanampoana. One historic source claimed that 25,000 subjects participated in the raising of the building's corner posts alone. The harsh working conditions were said to have been the cause of many deaths, although precise figures are unknown.[44]

Due to the deterioration of the wood of the exterior balconies over time,[45] Queen Ranavalona II commissioned James Cameron to reinforce and encase the original structure in a stone shell in 1867. Cameron's exterior replaced the wooden balconies with stone walls three stories high. On each of the three floors, seven arched windows run the length of the two longer side walls while five windows illuminate the shorter front and back walls. A square tower stands at each of the four corners of the stone shell, extending above the level of the walls and forming their junction.[16] A clock and bells were installed in the north-eastern tower.[45]

The ground floor of Manjakamiadana was divided into two vast rooms[16] with furniture and decor that reflected European influence but with placement of objects respecting the norms of Malagasy cosmology.[46] Following the reign of Radama II, the building was no longer inhabited but instead was reserved for state occasions.[47] The northernmost of these two rooms was the site of the signing of important trade treaties with British and American dignitaries.[16] It was also opened annually for the celebration of the Fandroana (Royal Bath) ceremony.[48] Following the imposition of French colonial rule, Manjakamiadana was transformed in 1897 into L'Ecole Le Myre de Vilers (Le Myre de Vilers School), a training centre for Malagasy civil servants employed by the French colonial regime.[49] When the purpose of the building changed, the elevation of the main hall's floor was raised by building a platform on top of the original wooden floor.[22]

Tranovola

Tranovola was first built in the Rova compound for Radama I in 1819 by Gros, then later reconstructed by Jean Laborde in 1845 on the orders of Queen Ranavalona I for her son Radama II.[35] The origin of the name Tranovola, meaning "Silver House", derives from the silver ornamentation used to decorate the exterior of the building. Sources have offered varying accounts of this silver decoration, including silver nails reportedly used to affix the roof, silver ornamentation on the window and door casings,[50] tiny silver bells hung from the roof,[6] and tiny mirrors embedded in the interior and exterior walls.[51] Another account describes silver "fringes" on the west side of the building, and gable decorations consisting of silver "buttons" and decorative images made from pounded silver.[6] After the supposed assassination of Radama II in 1863, the palace was used by Prime Ministers Rainivoninahitriniony and Rainilaiarivony to receive ambassadors and conduct the diplomatic affairs of the Kingdom of Madagascar.[49]

Built entirely of wood and surrounded by two stacked verandas around a central interior pillar supporting a steeply pitched roof, the exterior walls of Tranovola were painted red while the roof and railings of the verandas were painted white.[40] Prior to its 1845 remodel, the original 6-metre (20 ft) long and 7.2-metre (24 ft) wide Tranovola took shape in several stages over the course of Radama's reign.[52] The initial building was a two-storey house that in other respects largely followed the traditional architectural norms of the noble class in the highlands. Some time later a balcony was added on the second floor. This was eventually replaced by wraparound verandas on both floors, from which the king would deliver his royal speeches to the crowd gathered below.[53]

There were two key catalysts beyond Radama's affinity for Creole architecture that inspired Gros to innovate so far beyond traditional construction norms: the recent construction of a two-storey house with a balcony in the neighbourhood of Andohalo by a British missionary (the first balcony in highland Madagascar), and the 1823 arrival of Princess Rasalimo to the Rova, necessitating the redesign of Bevato as her residence. Rasalimo, whose marriage to Radama secured the peace between the Merina Kingdom and that of her Sakalava people on the west coast, was made Radama's principal wife and reportedly demanded an exceptional palace for her home. This request led Radama to employ a Creole architect named Jean Julien to design the unprecedented two-storey house.[53] Although historic sources are divided on whether Tranovola, Bevato or Marivolanitra was the first two-storey house at the Rova, the innovations embodied in these buildings and particularly in Tranovola underscore the rising influence of foreign architectural norms in Imerina. Tranovola is widely represented by historians as the first true example of the hybridisation of Merina architectural norms and those of Europe, and its design served as a model for the larger Manjakamiadana palace some years later. The innovative features of this building and the Manjakamiadana it inspired—particularly the verandas supported by exterior columns—became the new norm in highlands architecture, especially upon the adoption of brick as the principal building material.[54]

On each floor of the two-storey building, the floor plan consisted of a large central room flanked on either side by two smaller rooms.[39] Although the interior was laid out according to traditional cosmological norms with a north-south orientation and central supporting pillar, the decor was entirely innovative. Tranovola was the first building in Imerina to feature glass windows. Its walls were inlaid with mirrors[51] and painted with naive art frescoes of Merina sovereigns and royal army imagery in a style that has drawn comparisons with French 19th century Épinal prints.[39] The building's fine silk brocaded curtains, chandeliers, cabinets in ebony and gold, and sculptures in alabaster and bronze were remarked upon by a European visitor in 1823, as were the colourful fabric wall coverings imported from England.[51] During the reign of Ranavalona I, Crown Prince Rakoto (later King Radama II) occupied Tranovola as his personal residence. After the Queen's death, Radama continued to occupy rooms on the second storey of the building, using the smaller rooms on the ground floor as storage space.[55] A British visitor in 1873 reported that the wooden floors of Tranovola were highly polished, while the walls were hung with French wallpaper and decorated with imported mirrors and oil paintings including a portrait of Queen Victoria given as a gift to Radama II. Just inside the front door sat a seven-pound Armstrong gun in its carriage with numerous imported sofas, costly decorative objects and other items placed throughout the vast space.[47]

Under Gallieni's colonial administration, Tranovola was annexed to L'Ecole le Myre de Vilers housed in the nearby Manjakamiadana.[49] Later, in 1902, Tranovola became the headquarters of the Académie Malgache (Malagasy Academy) before being transformed into a museum of palaeontology.[35]

Manampisoa

Manampisoa, also called Lapasoa ("Beautiful Palace"), was a small villa in the form of a cross designed by James Cameron for Queen Rasoherina.[35] Construction was overseen by William Pool.[39] After the first corner post of the building was raised on 25 April 1865, work continued for two years before Manampisoa was complete. Measuring approximately 19 metres (62 ft) long, 9.1 metres (30 ft) wide and 15 metres (49 ft) high,[16] the structure was built using traditional vertical wood wall boards topped by a wooden roof and featured sliding windows protected by heavy wooden shutters.[49] It was built on a site formerly occupied by the wooden house called Marivolanitra, which was relocated to Mahazoarivo to make room for the new building.[48]

Inside, the layout consisted of two floors with four rooms each, linked by a central staircase with a decorative wooden balustrade. Ebony and rosewood were used for the interior panelling, floors and ceilings while the floor of the central hall exhibited a diamond parquet design in oak and rosewood.[39] An 1873 visitor described the floor as "highly polished ... all right enough for bare feet but rather slippery for boots". Wallpaper adorned the walls of the central hall, which was approximately 15 metres (49 ft) long, 6.1 metres (20 ft) wide and 3.7 metres (12 ft) high. The queen's couch occupied the northeast corner of the room, a space reserved for the ancestors according to traditional Malagasy cosmology, where she would receive visitors in repose.[49] A room formerly used as an office by Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony occupied the portion of the second floor facing the stairway.[39]

Manampisoa was one of the residences of queens Rasoherina, Ranavalona II and Ranavalona III, the last three monarchs of the Kingdom of Madagascar.[47] Once complete, Manampisoa was used by Rasoherina as her primary residence but the queen was only able to inhabit the house for approximately one year before dying in April 1868. After Rasoherina's death, her successor, Ranavalona II, used the building as a temporary worship space during work on the stone chapel.[48] Upon the collapse of the monarchy following French colonisation, the colonial authority transformed Manampisoa into a museum of Malagasy culture.[49]

Besakana and other houses

To the south of Manjakamiadana and Tranovola stood a number of smaller, older wooden houses, each between 15 metres (49 ft) and 18 metres (59 ft) high built in the traditional Merina architectural style reserved for the noble class. Three of these were of particular importance: Besakana, Mahitsy and Masoandro.[16]

Besakana is believed to have been the first residence of a Merina sovereign on the Rova site. Historical accounts claim that the first sovereign of Antananarivo, Andrianjaka, built the original Besakana as his personal residence at his newly established capital in the mid-17th century. This original building was torn down and reconstructed in the same design by Andriamasinavalona around 1680, and again by Andrianampoinimerina in 1800, each of who used the building as their personal residence. Radama I lived in Besakana for much of his time in the Rova compound.[35] The first school in Imerina was established at Radama's behest on 8 December 1820 by David Jones of the London Missionary Society to educate the children of the royal family. This school initially operated from Besakana for a short while until classes were transferred to the larger, recently remodelled Bevato nearby.[56] Sovereigns were enthroned in Besakana and their mortal remains were displayed here before burial.[16] A visitor writing in 1888 described this ancient building as "the official state room for civil affairs... regarded as the throne of the kingdom."[55]

Mahitsielafanjaka (Mahitsy) became the residence of Andrianampoinimerina after he moved his capital from Ambohimanga to Antananarivo.[39] Described in 1888 as the seat of ancestral spiritual authority at the Rova, the traditional sacrifice of a rooster during the ceremony of the Fandroana took place here, and ombiasy (astrologers) asked to perform sikidy (divination) for a sovereign would do so within this space.[55] The building also formerly housed a major royal idol called Manjakatsiroa[39] (or the entire collection of royal idols, according to another account) until the supposed public burning of all such relics by Queen Ranavalona II in 1869 following her conversion to Christianity.[16] Built in 1796, the traditional wooden Mahitsy follows traditional architectural norms: the roof is supported by the central pillar, and two superimposed beds—the highest for the king and the other for his wives—are located in the northeast corner, the portion of the home reserved for royalty and the ancestors. These beds are raised high off the ground to protect the sleepers from a nocturnal attack. Items formerly on display in this building after the end of the Merina monarchy in 1897 until the destruction of the original structure in the 1995 fire included Andrianampoinimerina's filanzana (palanquin), several wooden trunks and a pot of jaka (zebu confit) said to date from the king's reign.[39]

The name Masoandrotsiroa (Masoandro) was given to a series of buildings on the Rova grounds. The original Masoandro was one of the first three residences built by the Rova's founder, Andrianjaka, in the early 17th century,[12] and over time it became the house reserved for occupation by a new sovereign immediately following coronation.[55] This same Masoandro or a restored version of it was still standing on the Rova grounds and occupied by one of Andrianampoinimerina's wives two hundred years later.[21] However, historic sources offer seemingly contradictory or incomplete accounts of the fate of this historic building. A Masoandro was said to have been relocated from the Rova to Ambohimanga by Ranavalona I.[24] Another source states that Masoandro was demolished at the Rova by Ranavalona II and replaced by a house in brick, only to be demolished again by Ranavalona III. This last sovereign of Madagascar sought to build a new brick palace, also called Masoandro, with four square corner towers and a higher central tower modelled on the French Residence of Antananarivo. Work began in 1893 but was interrupted by war with France that led to colonisation and the collapse of the monarchy by 1896. The brick foundations of this unfinished Masoandro are still visible today.[57] Still another source states that Masoandro was one of three traditional wooden houses still standing at the Rova when Madagascar was colonised by the French, with the implication that the name was applied to distinct buildings at various times.[55]

Near the foundations of the brick Masoandro formerly stood Kelisoa, a traditional wooden structure which housed sacred animals[39] and concubines[6] at different points during the reign of Radama I and was later used by Ranavalona III to hold receptions. Also formerly standing here was Tsarahafatra ("Good Message"), a small palace built for Ranavalona I,[39] rebuilt after 1862, occupied as a primary residence by Ranavalona II and Ranavalona III,[48] and ultimately destroyed by French artillery in September 1895. By the 1960s, Besakana, Mahitsy and one other wooden house[39] (presumably the last wooden Masoandro[55]) were the only remaining examples of an estimated twenty ancient aristocratic houses that had occupied the Rova site during the reign of Andrianampoinimerina.[39] By 1975, this unidentified third house—said to be the oldest original structure on the grounds[39]—was no longer standing.[58]

Royal tombs

Nine royal tombs were located in the north-eastern quadrant of the Rova grounds. These included the two large tombs of King Radama I (d.1828) and Queen Rasoherina (d.1868), as well as seven ancient wooden tombs known collectively as the Fitomiandalana. These older tombs, the first of which was built in 1630 for King Andrianjaka, were a series of seven tomb pits topped with individual wooden trano masina (tomb houses) built close together in a row with their gable peaks aligned, followed by one tomb pit without a tomb house. Tomb houses are particular to highland tombs and are intended to indicate the noble rank of the deceased and house his or her spirit after death.[35]

Each tomb of the Fitomiandalana contained the bodies of early Kings of Imerina and their relatives, and was assigned a name after the principal occupant of the underlying grave. These were, in order: Andrianavalonibemihisatra (son of Andriamasinavalona and King of Antananarivo, five bodies), Andriamponimerina (son of Andriamasinavalona and King of Antananarivo at the time of future king Andrianampoinimerina's birth, three bodies), Andrianjakanavalomandimby (oldest son of Andriamasinavalona and King of Antananarivo, two bodies), Andriamasinavalona (great-grandson of Andrianjaka and King of Imerina, three bodies), Andriantsimitoviaminandriandehibe (grandson of Andrianjaka and King of Imerina, two bodies), Andrianjaka (founder of Antananarivo and King of Imerina, 12 bodies) and Andriantsitakatrandriana (son of Andrianjaka and King of Imerina, two bodies). The final tomb without a tomb house was for Andriantomponimerina (son of Andriamasinavalona and King of Antananarivo) and housed eight bodies.[13]

After the dissolution of the Kingdom of Madagascar, the French colonial authorities shifted the location of these tombs thereby disrupting the original cosmological symbolism of their arrangement.[35] When the original tombs were excavated for relocation, the French found the mortal remains of the nobles within had each been wrapped in numerous traditional lambas (woven silk cloths) then set within wooden coffins packed with charcoal. Bodies buried at Ambohimanga were found to have been entombed in the same way.[13]

Two more distinctive stone tombs were built beside the Fitomiandalana, to the north of Tranovola, the first of which was completed in 1828 by Louis Gros for Radama I. Further north, the second tomb was originally built for Queen Rasoherina by James Cameron in 1868.[16] Both of these stone tombs were topped with a tomb house.[35] Radama's tomb bears features popularised during the reign of his father, Andrianampoinimerina: three superimposed levels (excluding the tomb house) with upright sheets of stone at the base level, one of which could be removed to provide access to the subterranean chamber where the sovereign's body was laid upon a massive stone slab. Radama's tomb house broke with tradition by replacing the usual miniaturised version of the aristocratic wooden house (typified by Besakana and other ancient houses in the Rova grounds) with a house featuring a veranda, an architectural novelty introduced during his reign. The roof of this tomb house was originally thatch made from rushes but was replaced in the 1850s with wooden shingles, an innovation introduced from nearby Reunion Island or Mauritius. By contrast, the tomb of Rasoherina, erected forty years later, featured a two-level base (excluding the tomb house) made of chiselled stone blocks held together with cement.[59]

General Joseph Gallieni ordered the disinterment of the Merina sovereigns buried 21 kilometres (13 mi) away at Ambohimanga and had them reburied at the Rova.[60] The bodies of Radama II and Andrianampoinimerina were added to the tomb of Radama I, while those of Ranavalona I and Ranavalona II went into the tomb of Rasoherina. Several decades later in 1938, the body of Ranavalona III, who died in 1917 at her place of exile in Algiers (Algeria), was added to those of the other queens of Madagascar at the Rova. During the 1995 fire, heat from the burning wooden structures within the Rova compound caused the stone tombs to explode, leaving the mortal remains of generations of Merina sovereigns to be consumed by the flames.[35]

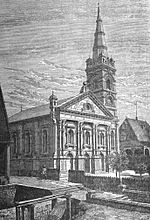

Fiangonana

Built by William Pool for Ranavalona II, Fiangonana ("Chapel") required eleven years to complete.[16] The structure's foundation stone was laid on 20 July 1869,[61] and its subsequent construction used over 35,000 hand-chiselled stones.[37] Inaugurated on 8 April 1880,[35] the central worship space measured 12.9 metres (42 ft) wide and 18.5 metres (61 ft) in length with an estimated capacity of 450 persons. The building was designed with a private pew for the royal family, elevated on a platform approximately 0.91 metres (3.0 ft) high and accessed by a short staircase. A private entrance available to the royal family was accessible by a decorative exterior bridge linking the chapel to the raised embankment upon which Manampisoa stood.[61]

The chapel boasts a number of distinctive features. At the time of its completion, its 34-metre (112 ft) tower was the only structure in Madagascar to be roofed in locally sourced slate. The windows were decorated with stained glass, and a pipe organ was installed to provide music at services. The organ and stained glass were imported from England,[61] while the pews, altar panels and queen's private pew were all ornately crafted from indigenous precious woods by local artisans.[37] During the colonial period, the chapel was used briefly as an exhibition space for European paintings before being closed to the public.[35]

Destruction

On the night of 6 November 1995, a fire broke out in the Rova compound, destroying or severely damaging all of its buildings.[62] Once the flames had been extinguished, all that remained of the original structures were the stone shells of the royal chapel and Manjakamiadana. Fire-fighters arrived late at the scene. Their capacity to douse the fire was hampered by the discovery that their fire hoses did not properly fit onto the nearby hydrants. In addition, the water pressure at the hydrants was significantly reduced due to Analamanga hilltop's high elevation. As the fire-fighters battled the flames, numerous bystanders ran into Rova compound buildings to retrieve artefacts of historic and cultural significance. Approximately 1,675 objects were saved out of an estimated total of 6,700. Some pillaging is believed to have occurred.[63] On the night of the fire, the body of one of the queens was found in the public square in the centre of the city. Although a funeral vigil was held the following day for these royal remains, the body was never identified.[62]

The destruction of the Rova of Antananarivo occurred at a time when the complex was in the final stages of the process to become classified as Madagascar's first cultural UNESCO World Heritage Site.[64] Six people were initially charged in connection with the Rova's destruction in an Antananarivo court of law,[46] but the official investigation concluded that the fire was an accident.[63] Public accusations of a cover-up placed the blame for the fire on government officials, various ethnic groups, foreign powers and other parties.[62] Over fifteen years after the fire, the widespread belief persists within and outside Madagascar that a deliberate arson was the cause.[65] Rumoured justifications for arson at the Rova were numerous and remain unproven. The revelation that important financial archives had been destroyed early on the morning of the fire sparked rumours that corrupt government officials had lit the blaze to create a public distraction from their illicit activities. Other explanations have included popular dissatisfaction with the election of divisive mayor Guy Willy Razanamasy or a flare-up of long-standing tensions among coastal peoples resentful of Merina socio-political domination. Accusations were also made against both then-president Albert Zafy and his predecessor, Didier Ratsiraka. The debate over why and how the Rova burned remains an unresolved and highly contentious issue almost two decades later.[63]

Reconstruction

Shortly after the fire, the government of Madagascar established the Direction nationale des opérations Rova (DNOR, or National Office of Rova Operations), a body directed by four national experts within Madagascar's Ministry of Culture who were tasked with developing and overseeing plans for the reconstruction of the Rova. Two years after the fire, several key milestones in the process had been achieved, with objects recovered from the fire inventoried, site excavations completed, preliminary restoration plans for Manjakamiadana developed, and work on the royal chapel initiated. A ramp was also built to enable site access for the necessary heavy construction vehicles. Prior to work commencing, a traditional ceremony was performed to restore the sanctity of the site, which had served a dual role as both a physical tomb and spiritual link to venerated ancestors.[66]

Estimated initial reconstruction costs were put at 20 million U.S. dollars by experts from UNESCO,[66] which was the principal contributor of funds as well as expertise due to the Rova's then status as a soon-to-be officially recognised World Heritage Site. The French Development Agency also pledged tens of thousands of dollars to the project while additional monies in the form of private donations from residents of Antananarivo helped to fund the reconstruction of the tombs on the complex.[66] However, according to a UNESCO report released in June 2000, the majority of funds raised by UNESCO between 1997 and 2000 for the Ratsiraka administration's Rova reconstruction initiative—an estimated 700 billion Malagasy Francs—were allegedly embezzled by the DNOR Administrator, stalling reconstruction at the end of the planning stage.[67]

Significant progress toward reconstruction was seen under the administration of President Marc Ravalomanana (2001–2009) who created the Comité national du patrimoine (CMP, or National Heritage Committee) responsible for overseeing the effort. The less time-intensive restoration projects were the first to be undertaken and completed. Efforts to restore the chapel, the monument least affected by the fire due to its stone structure,[66] focused particularly on restoring its roof, steeple and wooden pews along with altar panels that had burned in the fire. Work on the chapel was completed in 2003. Reconstruction work on Mahitsy began in 2001 and was completed in January 2003, while Besakana was rebuilt beginning in December 2003. The restoration of the nine royal tombs in the Rova complex was completed in October 2003.[37] In early January 2006, Phase 1 of the Manjakamiadana reconstruction commenced. This phase was scheduled for completion in May 2008.[38] The reconstruction of the larger wooden palaces, such as Tranovola and Manampisoa, has not been planned.[37]

The original exterior of Manjakamiadana comprised over 70,000 granite stones, of which approximately 20,000 had become cracked during the fire and needed replacement.[38] The western wall of the palace partially collapsed in January 2004 and required complete rebuilding.[63] Every stone was removed and numbered to facilitate the reinsertion of each one in its original place with two French stone-masonry companies engaged to supervise the work.[38] The foundation was modernised, first using laser technology to assess the topography of the site, then by driving 22 cement piles into the ground beneath the foundation base to a depth of 23 metres (75 ft).[38] Phase 2 consisted of replacing each of the numbered exterior wall stones in its original place, bolstered where needed by new stones to replace those damaged in the fire. Although the palace interior was originally made of wood, the reconstructed building was designed using reinforced concrete interior supporting beams for the walls, ceiling and roof due to concerns over the availability and durability of hardwood.[68] Finally, the roof was re-tiled in blue-gray slate imported from quarries near the French city of Angers.[38]

Phases 1 and 2 of the reconstruction process were declared complete in December 2009 at a total cost of 6.5 million euros. The work employed 230 people at three sites: a granite quarry on National Route 1 (RN1), a separate site where the stones were chiselled into shape, and the site of the Rova itself.[38] Phase 3 will consist of the design and rebuilding of the interior of the palace, while Phase 4 will involve planning and subsequent development of the display and management of the museum collection to be housed on the ground floor. Work on these final two phases of reconstruction was scheduled to begin in 2011 with completion expected within 24 months at a cost of approximately 3,765,000 euros.[69] Between the completion of the first two phases and the beginning of work on the second two phases, the Minister of Culture and Heritage fast-tracked the enclosure of windows and doors to protect the building's interior and began establishing a new inventory of historic objects saved from the fire. These artefacts are currently housed in the Andafiavaratra Palace, former home of late 19th-century Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony, and will be transferred to a museum within Manjakamiadana upon its completion.[70]

In March 2009 the Ravalomanana administration was ousted following several months of opposition protests led by then-mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina. The unconstitutional transfer of power to Rajoelina, who adopted the title of President of the High Transitional Authority (HAT), was widely viewed as a coup d'état by members of the international community, leading many bilateral and intergovernmental donors to suspend non-humanitarian support to the regime.[71][72][73][74] The HAT has declared its intention to continue the Manjakamiadana reconstruction project using a combination of state funds and donations from private Malagasy citizens. Six banking agencies in Madagascar have been selected to serve as collection points for private donations.[75] On 7 March 2011 the HAT relieved the original members of the National Heritage Committee of their posts and mandated the appointment of new members selected from among the current regime's ministerial staff. Despite the introduction of these diverse strategies, the HAT has struggled to obtain adequate funds to continue the pace of Rova reconstruction seen in the latter half of the Ravalomanana presidency, and progress toward completion has advanced sporadically at a gradual rate since autumn 2009.[76][77]

Notes

- ^ Razafimahazo, S. "Vazimba: Mythe ou Realité?". Revue de l’Océan Indien. Madatana.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60TJDOhuq. Retrieved 26 July 2011. (French)

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (1993). "The Structure of Trade in Madagascar, 1750–1810". The International Journal of African Historical Studies 26 (1): 111–148. doi:10.2307/219188.

- ^ Ranaivoson (2005), p. 35

- ^ Fage & Oliver (1975), p. 468

- ^ a b c Nativel (2005), p. 59

- ^ a b c d e f g Nativel (2005), p. 79

- ^ Shillington (2005), pp. 158–159

- ^ a b Desmonts (2004), pp. 114–115

- ^ Buyers, Christopher. "The Merina (or Hova) dynasty". www.royalark.net. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5wZch7no6. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Chapus & Dandouau (1961), pp. 47–48

- ^ Government of France (1898), pp. 918–919

- ^ a b c Kus, Susan; Raharijaona, Victor (2000). "House to Palace, Village to State: Scaling up Architecture and Ideology". American Anthropologist, New Series 1 (102): 98–113.

- ^ a b c d Government of France (1898), p. 919

- ^ Piolet (1895), p. 210

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 64

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Oliver (1886), pp. 240–242

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 30

- ^ Berg, Gerald M. (1988). "Sacred Acquisition: Andrianampoinimerina at Ambohimanga, 1777–1790". The Journal of African History 29 (2): 191–211. doi:10.1017/S002185370002363X.

- ^ "Royal Hill of Ambohimanga". UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/950. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 50

- ^ a b c d e f Government of France (1898), pp. 923–925

- ^ a b c Government of France (1898), p. 924

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 52

- ^ a b c d Nativel (2005), p. 53

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 65

- ^ Mutibwa & Esoavelomandroso (1989), pp. 412–447

- ^ a b Nativel (2005), p. 75

- ^ a b Government of France (1898), pp. 926–927

- ^ a b Acquier (1997), pp. 63–64

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 102

- ^ a b Government of France (1898), p. 925

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 24

- ^ Nativel (2005), pp. 109–110

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 117

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Frémigacci (1999), pp. 421–444

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f Andrianaivo-Golz, Olga; Golz, Peter. "The Rova of Antananarivo". www.madainfo.de. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5yAvfWfRX.

- ^ a b c d e f g Editor (2 December 2010). "Patrimoine – La première phase des travaux terminée: Le "rova" renaît de ses cendres". Le Quotidien de la Réunion et de l'Océan Indien (Antananarivo, Madagascar). (French)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ranaivo & Janicot (1968), pp. 131–133

- ^ a b Sibree & Monod (1873), p. 101

- ^ a b Nativel (2005), p. 90

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 93

- ^ Sedson, Annick. "Des découvertes sur le Rova de Manjakamiadana". www.haisoratra.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vlhrAzj7. Retrieved 13 February 2010. (French)

- ^ Nativel (2005), pp. 88–89

- ^ a b Religious Tract Society (1883), p. 341

- ^ a b "A national treasure lost forever". The Economist (London): p. 88. 9 December 1995.

- ^ a b c Chiswell (1893), pp. 459–466

- ^ a b c d Nativel (2005), p. 112

- ^ a b c d e f Government of France (1900), pp. 279–282

- ^ Le Chartier & Pellerin (1888), p. 239

- ^ a b c Nativel (2005), p. 82

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 81

- ^ a b Nativel (2005), pp. 79–81

- ^ Acquier (1997), pp. 90–91

- ^ a b c d e f Featherman (1888), p. 332

- ^ Ralibera (1993), p. 196

- ^ Nativel (2005), p. 110

- ^ Belrose-Huyghues, V. (1975). "Un exemple de syncrétisme esthétique au XIXe siècle: Le Rova de Tananarive d'Andrianampoinimerina à Radama I". Omaly sy Anio 1–2: 75–83. (French)

- ^ Acquier (1997), p. 172

- ^ Bradt (2011), p. 165

- ^ a b c McPherson Campbell (1889), pp. 65–70

- ^ a b c Rakotoarisoa, Jean-Aimé (date unknown). "Fire of the Rova, the Queen’s Palace, in Antananarivo". Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vlhy4VUE. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d Fournet-Guérin (2007), p. 297

- ^ Commission of the European Communities (March–April 1996). The ACP-EU Courier 20 (156).

- ^ Bradt (2011), p. 162

- ^ a b c d Rakotoarisoa, Jean-Aimé (June 1998). "The Palace of the Kings and Queens of Madagascar". The African Archaeological Review 15 (2): 97–99.

- ^ Galibert (2009), p. 92

- ^ Editor (6 November 2007). "Reconstruction du Rova: Recours aux financements extérieurs". Madagascar Tribune (Antananarivo, Madagascar). Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vwL0ijF2. (French)

- ^ Ratsara, Domoina (15 November 2010). "Manjakamiadana: La finition demande financement". L'Express de Madagascar (Antananarivo, Madagascar). Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vli8vZ5W. (French)

- ^ R., M.K. (8 November 2010). "Rova Manjakamiadana: 15 ans après". La Gazette de la Grande Ile (Antananarivo, Madagascar). Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/5vwKf9TN5. (French)

- ^ Pourtier, Gregoire (17 March 2009). "Isolated Madagascar president faces end of reign". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62e4Ir4hG. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Lough, Richard (19 March 2009). "Norway says Madagascar aid freeze in force". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62e4U1GNa.

- ^ Heinlein, Peter (17 March 2009). "AU Warns Madagascar Opposition Not to Seize Power". VOA News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62e4s78Gv. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "SADC suspends Madagascar". BUA News. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62e5FCiYx. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Ratsara, Domoina (24 May 2011). "Patrimoine: Manjakamiadana en dernières phases". L'Express de Madagascar (Antananarivo, Madagascar). Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/60S29R6cU. (French)

- ^ Andrianina, Tsiry (23 October 2011). "Culture et patrimoine: Qu’a fait le ministère de tutelle?". Les Nouvelles (Antananarivo, Madagascar). Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62dxAMeUQ. (French)

- ^ "Palais de la Reine: Rénovation en panne". Courrier de Madagascar (Antananarivo, Madagascar). 23 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. http://www.webcitation.org/62e1Psbi6. (French)

References

- Acquier, Jean-Louis (1997). Architectures de Madagascar. Paris: Berger-Levrault. ISBN 2-7003-1169-8. (French)

- Bradt, Hillary (2011). Madagascar (10th ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-84162-341-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=uTRPnMlOcwgC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Chapus, Georges-Sully; Dandouau, Andre (1961). Manuel d'histoire de Madagascar. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. (French)

- Chiswell, Alfred (1893). "A visit to the Queen, Madagascar". The Newberry house magazine, Volume 2. London: Elsevier. http://books.google.com/books?id=ev9JAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Desmonts, Annick (2004). Madagascar. New York: Éditions Olizane. ISBN 2-88086-387-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=x57t6B-wo6kC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Fage, J.D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975). The Cambridge history of Africa. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20413-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=BOHYn7J4YzQC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Featherman, Americus (1888). Social history of the races of mankind Volume 2, Part 2. London: Trübner & Co. http://books.google.com/books?id=Gw-gAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Fournet-Guérin, Catherine (2007). Vivre à Tananarive: géographie du changement dans la capitale malgache. Paris: Karthala Éditions. http://books.google.com/books?id=U_NHlyeI3mcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Frémigacci, Jean (1999). "Le Rova de Tananarive: Destruction d'un lieu saint ou constitution d'une référence identitaire?". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre. Histoire d'Afrique. Paris: Éditions Karthala. (French)

- Galibert, Didier (2009). Les gens du pouvoir à Madagascar: État postcolonial, légitimités et territoire, 1956–2002. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Éditions. ISBN 2-8111-0213-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=TiRtPAfauLwC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Government of France (1898). "L'habitation à Madagascar". 4. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Imprimerie Officielle de Tananarive. http://books.google.com/books?id=Jp3FAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Government of France (1900). Annuaire général de Madagascar et dépendances. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Imprimerie Nationale. ISBN 3-540-63293-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=IXJKAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Le Chartier, Henri; Pellerin, G. (1888). Madagascar depuis sa découverte jusqu'à nos jours, Volume 20. Paris: Jouvet et Cie. http://books.google.com/books?id=hXgLAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- McPherson Campbell, Belle (1889). Madagascar: Volume 8 of Missionary Annuals. Chicago, Illinois: Woman's Presbyterian board of missions of the northwest. http://books.google.com/books?id=yVs-AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Mutibwa, P.M.; Esoavelomandroso, F.V. (1989). "Madagascar: 1800–80". In Ade Ajayi, Jacob Festus. General History of Africa VI: Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 0-520-06701-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=sMpMuJalFKoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Nativel, Didier (2005). Maisons royales, demeures des grands à Madagascar. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Éditions. ISBN 978-2-84586-539-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=8IOZLvSrspIC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Ogot, Bethwell (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-101711-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=WAQbp7aLpZkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: an historical and descriptive account of the island and its former dependencies, Volume 1. London: Macmillan. http://books.google.com/books?id=lKtBAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Piolet, Jean-Baptiste (1895). Madagascar et les Hova: description, organisation, histoire. Paris: C. Delagrave. http://books.google.com/books?id=OokwAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Ralibera, Daniel (1993). Madagascar et le christianisme. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Editions Karthala. http://books.google.com/books?id=GOeAT76TGN0C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

- Ranaivo, Flavien; Janicot, Claude (1968). Les guides bleues: Madagascar. Paris: Librairie Hachette. (French)

- Ranaivoson, Dominique (2005). Madagascar: dictionnaire des personnalités historiques. Paris: Sépia. (French)

- Religious Tract Society, ed (1883). "Antananarivo, the Capital of Madagascar". The Sunday at Home. 30. London: Religious Tract Society. http://books.google.com/books?id=TJ1HAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African history, Volume 1. New York: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-57958-453-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ftz_gtO-pngC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Sibree, James; Monod, Henry (1873). Madagascar et ses habitants: journal d'un séjour de quatre ans dans l'île. London: Société des livres religieux. http://books.google.com/books?id=sRAYisfUJ48C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. (French)

External links

Media related to Rova of Antananarivo at Wikimedia CommonsCategories:

Media related to Rova of Antananarivo at Wikimedia CommonsCategories:- African architecture

- Buildings and structures in Antananarivo

- Former palaces

- History of Madagascar

- Palaces in Madagascar

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.