- Mamluk rule in Iraq

-

The Mamluks (Arabic: مماليك mamālīk, Georgian: მამლუქები) who ruled Iraq in the 18th century were freed Georgian slaves[1] converted to Islam, trained in a special school, and then assigned to military and administrative duties. They presided, with short intermissions, over more than a century in the history of Ottoman Iraq, from 1704 to 1831. The Mamluk ruling elite, composed principally of officers from Georgia and Circassia, succeeded in asserting autonomy from their Ottoman overlords, and restored order and some degree of economic prosperity in the region. The Ottomans overthrew the Mamluk regime in 1831 and gradually imposed their direct rule over Iraq, which would last until World War I.

Contents

Background

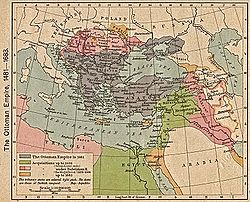

Throughout most of the period of Ottoman rule (1533-1918) the territory of present-day Iraq was a battleground between the rival Ottoman Empire and Safavid Iranians. The region suffered from frequent inter-clan struggles.[2]

The tribal problem[clarification needed] was perhaps one of the main reasons why Sultan Ahmed III (1703–30), whose reign was marked by relative political stability and extensive reforms, allowed Hasan Pasha, the pasha of Baghdad, of Georgian origin (1704-1723), to build up the first Iraqi Mamluk force. Hasan's son and successor, Ahmed, continued to recruit the Mamluks and promoted them to key administrative and military positions. Both Hasan and Ahmed rendered a valuable service to the Ottoman Porte by curbing the unruly tribes and securing a steady inflow of taxes to the treasury in Constantinople as well as by defending Iraq against yet another military threat from the Safavids of Iran. By the time when Ahmed Pasha died in 1747, his Mamluks had been organized into a powerful, self-perpetuating elite corps of some 2,000 men ("Georgian Guard"). On Ahmed's death, the sultan attempted to prevent these Mamluks from assuming power and sent an outsider as his wali in Baghdad. However, Ahmed’s son-in-law Suleyman Abu Layla, already in charge of Basra, marched on Baghdad in the head of his Georgian guard and ousted the Ottoman administrator, thereby inaugurating 84 years of the Mamluk rule in Iraq.[3]

Mamluk rulers

By 1750, Suleyman Abu Layla had established himself as an undisputed master at Baghdad and had been recognized by the Porte as the first Mamluk pasha of Iraq. The newly established regime embarked on a campaign to gain more autonomy from the Ottoman government and to curb the resistance of the Arab and Kurdish tribes. They managed to counter the Al-Muntafiq threats in the south and brought Basra under their control. They encouraged European trade and allowed the British East India Company to establish an agency in Basra in 1763.

The successes of Mamluk regime, however, still depended on their ability to cooperate with their Ottoman suzerains and religious elite within Iraq. The Porte sometimes employed force to depose the recalcitrant pashas of Baghdad, but the Mamluks were able to retain their hold of the pashalik, and even enlarged their domains. They failed, however, to secure a regular system of succession and the gradual formation of rival Mamluk households resulted in factionalism and frequent power struggles. Another major menace to the Mamluk rule came from Iran whose resurgent ruler, Karim Khan, invaded Iraq and installed his brother Sadiq Khan in Basra in 1776 after a protracted and stubborn resistance offered by the Mamluk general Suleyman Aga. The Porte hastened to exploit the crisis and replaced Umar Pasha (1764-76) with a non-Mamluk, who proved incapable of keeping order.[3]

After Karim’s death in 1779, Sadiq withdrew from Basra while Suleyman returned from his exile in Shiraz and acquired the governorship of Baghdad, Basra and Shahrizur in 1780.[4] This Süleyman Pasha is known as Büyük, i.e., the Great, and his rule (1780-1802) was efficient at first, but weakened as he grew older. He imported large numbers of Georgians to strengthen his clan, asserted his supremacy over the factionalized Mamluk households and restricted the influence of Janissaries. He fostered economy and continued to encourage commerce and diplomacy with Europe, which received a major boost in 1798 when Süleyman Pasa gave permission for a permanent British agent to be appointed in Baghdad.[5] However, his struggle against the Arab tribes was less successful and the troubles culminated in the sack of the Shiite shrine at Kerbala by the Wahhabi in 1801.[4]

Süleyman Pasa was succeeded after a power struggle in 1802 by Ali Pasha, who repelled the Wahhabite raids against Najaf and Al Hillah in 1803 and 1806 but failed to challenge their domination of the desert. After Ali’s assassination in 1807, his nephew Süleyman Pasa the Little took over the government. Inclined to curtail provincial autonomies, Sultan Mahmud II (1808-39) made his first attempt to oust the Mamluks from Baghdad in 1810. Ottoman troops deposed and killed Süleyman, but again failed to maintain control of the country. After yet another bitter internecine feud in 1816, Süleyman’s energetic son-in-law Daud Pasha ousted his rival Sa’id Pasha (1813-16; son of Süleyman Pasha the Great) and took control of Baghdad. The Ottoman government reluctantly recognized his authority.[3]

Daud Pasha, who would prove to be the last Mamluk ruler of Iraq, was a son of Ali. He was married with a' daughter of his Uncle Mameluk Süleyman the Great.

Daud Pasha initiated important modernization programs that included clearing canals, establishing industries, reforming the army with the help of European instructors, and founding a printing press. He maintained elaborate pomp and circumstance at his court. Besides the usual troubles with the Arab tribes and internal dissensions with sheikhs, he was involved in more serious fighting with the Kurds and the conflict with Iran over the influence in the Kurdish principality of Baban. The conflict culminated in the Iranian invasion of Iraq and the occupation of Sulaymaniyah in 1818. Later, Daud Pasha capitalized on the destruction of Janissaries at Istanbul in 1826, and eliminated the Janissaries as an independent local force.[3][5]

Meanwhile, the existence of the autonomous regime in Iraq, a long-time source of anxiety at Istanbul, became even more threatening to the Porte when Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt began to claim Syria. In 1830, the Sultan decreed Daud Pasha’s dismissal, but the emissary carrying the order was arrested at Baghdad and executed. In 1831, the Ottoman army under Ali Ridha Pasha marched from Aleppo into Iraq. Devastated by floods and an epidemic of bubonic plague, Baghdad capitulated after a token resistance. Daud Pasha, facing opposition from local clergymen within Iraq, surrendered to the Ottomans and was treated with favor. His life ended in 1851, while he was custodian of the shrine at Medina; the remaining Mamluks were exterminated.[3] The arrival of the Sultan’s new governor in Baghdad in 1831 signaled the beginning of a direct Ottoman rule in Iraq.[5]

See also

- Dynasty of Hasan Pasha

- Naji Shawkat, Prime Minister of Iraq from 1932 to 1933, who was the scion of one of the Georgian Mamluk clans.[6]

References

- ^ Basra, the failed Gulf state: separatism and nationalism in southern Iraq at Google Books By Reidar Visser

- ^ Litvak, Meir (2002), Shi'i Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: The 'Ulama' of Najaf and Karbala, pp. 16-17. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521892961.

- ^ a b c d e Kissling, H.J. (1969), The Last Great Muslim Empires, pp. 82-85. Brill, ISBN 9004021043.

- ^ a b "Iraq". (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 15, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b c "Iraq". (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 15, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Ghareeb, Edmund A. (2004), Historical Dictionary of Iraq, p. 220. Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0810843307.

Further reading

- Nieuwenhuis, Tom (1982), Politics and Society in Early Modern Iraq: Mamluk Pashas, Tribal Shayks and Local Rule between 1802 and 1831. Springer, ISBN 9024725763.

Categories:- History of Iraq

- History of the Ottoman Empire

- History of Georgia (country)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.