- Dunmore's Proclamation

-

Dunmore's Proclamation

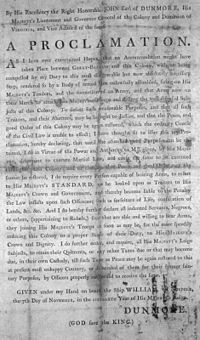

A copy of the original printingCreated November 7, 1775 Ratified November 14, 1775 Authors John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore Purpose To declare martial law, and to encourage slaves of rebels in Virginia to leave their masters and support the Loyalist cause Dunmore's Proclamation is a historical document issued on November 7, 1775, by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, royal governor of the British Colony of Virginia. The Proclamation declared martial law[1] and promised freedom for slaves of American patriots who left their masters and joined the royal forces.

Contents

Background

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, originally from Scotland, was the royal governor of the Colony of Virginia from 1771 to 1775. During his tenure, he worked proactively to extend Virginia's Western borders past the Appalachian Mountains, despite the British Royal Proclamation of 1763. He notably defeated the Shawnee nation in Dunmore's War, gaining land south of the Ohio River. As a widespread dislike for the British crown (as a result of the American Revolution) became apparent, however, Dunmore changed his attitude towards the colonists; he became frustrated with the their lack of respect towards the British Crown. Dunmore's popularity decreased worsened after Dunmore, under British command, attempted to prevent elections for the Second Continental Congress.[2]

On April 21, 1775, he attempted to seize colonial ammunition stores, and met an angry mob. The colonists argued that the ammunition belonged to them, not to the British Crown. That night, Dunmore angrily swore, "I have once fought for the Virginians and by God, I will let them see that I can fight against them." This was one of the first instances that Dunmore overtly threatened to institute martial law. While he had not formally passed any rulings, news of his plan spread through the colony rapidly.[3] A group of slaves offered their services to the royal governor not long after April 21. Though he ordered them away, the colonial slaveholders remained suspicious of his intentions.[4]

As colonial protests became violent, Dunmore fled the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg and took refuge aboard the frigate HMS Fowey at Yorktown on June 8, 1775. For several months, Dunmore replenished his forces and supplies by conducting raids and inviting slaves to join him. When Virginia's House of Burgesses decided that Dunmore's abdication indicated his resignation, he drafted the formal proclamation on November 7. He published the formal document a week later.[5][2]Dunmore's Proclamation

In the official document, he declared martial law and adjudged all patriots as traitors to the crown. Furthermore, the document declared "all indentured servants, Negroes, or others...free that are able and willing to bear arms..."[6] Dunmore expected such a revolt to have several effects. Primarily, it would bolster his own forces, which, cut off from reinforcements from British-held Boston, numbered only around 300.[7] Secondarily, he hoped that such an action would create a fear of a general slave uprising [8] amongst the colonists and would force them to abandon the revolution.[9]

Colonial Reaction

Virginians were outraged, and responded immediately.[10] Newspapers such as The Virginia Gazette published the proclamation in full, and patrols were organized to look for any slaves attempting to take Dunmore up on his offer. The Gazette not only criticized Dunmore for offering freedom to only those slaves belonging to patriots who were willing to serve him, but also questioned whether he would be true to his word, suggesting that he would sell the escaped slaves in the West Indies. the paper therefore cautioned slaves to "Be not then...tempted by the proclamation to ruin your selves."[11] As very few slaves were literate, this was more a symbolic move than anything. It was also noted that Dunmore himself was a slaveholder.[12]

On December 4, the Continental Congress recommended to Virginian colonists that they resist Dunmore "to the uttermost..."[8] On December 13, the Virginia Convention responded in kind with a proclamation of its own,[13] declaring that any slaves who returned to their masters within ten days would be pardoned, but those who did not would be punished harshly.

The only notable battle in which Dunmore's slaves participated was the Battle of Great Bridge, which was a decisive British loss. [8] Although few slaves reached Dunmore (estimates vary, but generally range between 800 and 2000),[14][15] it is estimated that up to 100,000 attempted to leave their masters and join the British.[16] Those escaped slaves who managed to join the British became known as Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment.[17] The strategy was ultimately unsuccessful as Dunmore's forces were decimated by a smallpox outbreak less than a year later. However, as the British were fleeing they took 300 of the former slaves with them. Although seemingly minuscule, more slaves found their freedom through this than any other way until the Civil War.[18]

See also

References

- ^ Scribner, Robert L. (1983). Revolutionary Virginia, the Road to Independence. University of Virginia Press. pp. xxiv. ISBN 0813907489.

- ^ a b "Earl of Dunmore". ABC-CLIO.

- ^ John E. Selby, Don Higginbotham (2007). The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783. Colonial Williamsburg. http://books.google.com/books?id=WfCBYZs_jIMC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=%22I+have+once+fought+for+the+virginians+and+by+god%22&source=bl&ots=5f563Jlgzu&sig=elEwVrS4u7598Jzkne58P-wEffI&hl=en&ei=4NygToDLGobt0gH06b2YCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22I%20have%20once%20fought%20for%20the%20virginians%20and%20by%20god%22&f=false.

- ^ Halpern, Rick (2002). Slavery and Emancipation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0631217355.

- ^ Halpern, Rick (2002). Slavery and Emancipation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0631217355.

- ^ Halpern, Rick (2002). Slavery and Emancipation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0631217355.

- ^ Proclamation of Earl of Dunmore. Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h42.html. Retrieved 2007-09-10

- ^ a b c Benjamin Quarles (195). "Lord Dunmore as Liberator". The William and Mary Quarterly. 3 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture) 15 (4). http://www.jstor.org/stable/2936904.

- ^ McPhail, Mark Lawrence (2002). The Rhetoric of Racism Revisited: Reparations Or Separation?. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 42. ISBN 0742517195.

- ^ Fiske, John (1891). The American Revolution. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. pp. 178–180.

- ^ Virginia Gazette, Dixon and Hunter, November 25, 1775, page 3. The Virginia Gazette. 1775-11-25. http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/VirginiaGazette/VGImagePopup.cfm?ID=4636&Res=HI. Retrieved 2008-11-04

- ^ Williams, George Washington (1882). History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers, and as Citizens. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 324–344.

- ^ Williams, George Washington (1887). A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Negro Universities Press. pp. 18.

- ^ Lanning, Michael Lee (2005). African Americans in the Revolutionary War. Citadel Press. pp. 59. ISBN 0806527161.

- ^ Raphael, Ray (2002). A People's History of the American Revolution: How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence. Harper Collins. pp. 324. ISBN 0060004401.

- ^ Bristow, Peggy (1994). We're Rooted Here and They Can't Pull Us Up: Essays in African Canadian Women's History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 19. ISBN 0802068812.

- ^ "Black Loyalists". http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/work_community/loyalists.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-10

- ^ Ruffins, Fath. Fath Ruffins on blacks' reaction to Dunmore's Proclamation. Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2i1615.html. Retrieved 2007-09-10

External links

- Photograph of the proclamation

- Proclamation text

- Proclamation of Earl of Dunmore from PBS

- Summary of Dunmore's Proclamation

- Dunmore's Proclamation:A Time to Choose

- Reactions of blacks to Dunmore's Proclamation

- Dunmore's Proclamation and the fear of slave revolt

- Controlling slaves after Dunmore's Proclamation

- Dunmore's Proclamation's effect on the war

- Significance of Dunmore's Proclamation

Virginia during the American Revolutionary War1774

1775 1776 1779 1781 Categories:- Documents of the American Revolution

- 1775 in the Thirteen Colonies

- Slavery in the United States

- Colonial Virginia

- Virginia in the American Revolution

- 1775 in Virginia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.