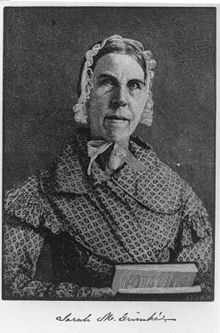

- Sarah Grimké

-

Sarah Moore Grimké (November 26, 1792 – December 23, 1873) was an American abolitionist, writer, and suffragist.

Contents

Early life

Sarah Grimké was born in South Carolina. She was sixth of fourteen children and the second daughter of Mary and John Faucheraud Grimké, a rich plantation owner who was also an attorney and a judge in South Carolina. Sarah’s early experiences with education shaped her future as an abolitionist and feminist. Throughout her childhood, she was keenly aware of the inferiority of her own education when compared to her brothers’ classical one, and despite the fact that everyone around her recognized her remarkable intelligence and abilities as an orator, she was prevented from obtaining a substantive education or pursuing her dream of becoming an attorney, due to these dreams being considered "unwomanly." [1] She received education from private tutors on appropriate subjects for young women of the time.[2]

Sarah’s mother Mary was a dedicated homemaker and an active member in the community. She was a leader in the Charleston’s Ladies Benevolent Society. Mary was also an active Episcopalian and gave some of her time to the poor of the community and women incarcerated in a nearby prison . Even though she had many responsibilities, Mary found time to read and comment on her readings with her son Thomas. Sarah’s mother was a busy woman and Sarah did not have her attention because “she couldn’t be bothered with child’s concerns.”[3]

Perhaps because she felt so confined herself, Sarah expressed a sense of connection with the slaves to such an extent that her parents were unsettled. From the time she was twelve years old, Sarah spent her Sunday afternoons teaching Bible classes to the young slaves on the plantation, and she found it an extremely frustrating experience. While she wanted desperately to teach them to read the scripture for themselves, and they had a longing for such learning, she was refused. Her parents claimed that literacy would only make the slaves unhappy and rebellious; they also suggested that mental exertion would make them unfit for physical labor. Also, teaching slaves to read was against the law in South Carolina since 1740.

She secretly taught her personal slave to read and write, but when her parents discovered the young tutor at work, the vehemence of her father’s response proved alarming. He was furious and nearly had the young slave girl whipped. Fear of causing such trouble for the slaves themselves prevented Sarah from undertaking such a task again.

When her brother Thomas went off to law school at Yale, Sarah remained at home. Thomas continued teaching Sarah during his visits back home from Yale with new ideas about the dangers of Enlightenment and the importance of religion. These ideas, combined with her secret studies of the law, gave her some of the basis for her later work as an activist. [4]. Her father supposedly remarked that if Sarah had only been a boy, "she would have made the greatest jurist in the country"[5] Not only did the denial of education seem unfair, Sarah was further perplexed that while her parents and others within the community encouraged slaves to be baptized and to attend worship services, these believers were not viewed as true brothers and sisters in faith.

From her youth, Sarah determined that religion should take a more proactive role in improving the lives of those who suffered most; this was one of the key reasons she later joined the Quaker community where she became an outspoken advocate for education and suffrage for African-Americans and women.[6]

In 1819 Sarah accompanied her dying father to Philadelphia.[7]. . As a result of her father's death, Sarah became more self-assured, independent, and morally responsible. Sarah stayed in Philadelphia a few more months after her father died and then met Israel Morris, who would introduce her to Quakerism, specifically the writings of John Woolman. [8].[9] She went back home and decided to go back to Philadelphia to become a Quaker minister, leaving her Episcopalian upbringing behind. Her endeavor was unsuccessful as she was repeatedly ignored and shut out by the male dominated council.[10]. She returned to Charleston, South Carolina, in the spring of 1827 to “save” her sister Angelina. Angelina visited Sarah in Philadelphia from July to November of the same year and returned to Charleston, committed to the Quaker faith. After leaving Charleston, Angelina and Sarah traveled around New England speaking in large parlors and small churches. Their speaches concerning abolition and women's rights reached thousands [11]. In November, 1829, Angelina joined her sister in Philadelphia. [12] The influence Sarah had on Angelina may had come from the relationship they had since they were young. For years, Angelina called her sister Sarah “mother.” Sarah was her godmother and her main caretaker since youth.[13]), this may explain why she felt the need to “save” Angelina from the limitations she faced in Charleston.

In 1868 Grimké discovered three illegitimate nephews that her older brother had had by his personal slave. Welcoming them into the family, she worked to provide funds to educate Archibald and Francis Grimké.[14].

Activism

Sarah and Angelina, although daughters of a plantation owner, had come to loathe slavery and all its degradations that they knew intimately. They had hoped that their new faith would be more accepting of their abolitionist beliefs than had been their former. However, their initial attempts to attack slavery caused them difficulties in the Quaker community. Nevertheless, the sisters persisted despite the additional complication caused by the belief that the fight for women's rights was as important as the fight to abolish slavery. They continued to be attacked, even by some abolitionists who considered their position too extreme. In 1836, Sarah published Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States. In 1837, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women was published serially in a Massachusetts newspaper, The Spectator, and immediately reprinted in The Liberator, the newspaper published by radical abolitionist and women's rights leader William Lloyd Garrison. The letters were published in book form in 1838.

When the sisters were both together in Philadelphia they were then able to fully devote themselves to the Quakers' Society of Friends and other various charity work. Sarah then began working towards becoming a clergy member. While Sarah was pursuing this she was continually discouraged by other male members of the church. It was at this time that Sarah came to the realization that though the church was something she agreed with in theory, it was not delivering on its promises.[citation needed] It was at this time that anti-slavery rhetoric began entering public discourse.

Joining her sister in the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836, Sarah originally felt that she had finally found the place where she truly belonged, in which her thoughts and ideas were encouraged. However, as Angelina and she began speaking not only on abolition, but also on the importance of women's rights, they both began to face much criticism. Their public speeches were seen as unwomanly because they spoke to mixed audiences, called "promiscuous audiences" at that time. Not only did they speak to mixed company, but they also publicly debated men who disagreed with them. This was too much for the general public of 1837 and caused many harsh attacks on their womanhood, one main thought being that they were both just poor "spinsters" displaying themselves in order to find any man who would be willing to take them. [15]

In 1838, her sister Angelina married the leading abolitionist Theodore Weld, who had been a severe critic of their inclusion of women's rights into the movement for abolition. She retired to the background of the movement while being a wife and mother, though not immediately. Sarah, however, took a severely back role, completely ceasing to speak. Apparently Weld wrote her a letter after a recent lecture she had given, detailing her inadequacies for speaking. He tried hard to explain that he wrote this out of love for her, but he made it clear that she was damaging the cause, not helping it, like her sister. However, as she received many requests to speak over the following years (as did Angelina), it is questionable whether her "inadequacies" which he described were really so bad. [16]

During the Civil War, Sarah wrote and lectured in support of President Abraham Lincoln.

Legacy/Influence

Sarah Moore Grimké was the author of the first developed public argument for women's equality and she strived to rid the United States of slavery, Christian churches which had become “unchristian,” and prejudice against African-Americans and women.[17]

Her writings gave suffrage workers such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott several arguments and ideas that they would need to help end slavery and begin the women’s suffrage movement.[18]

Sarah Grimke is categorized as not only an abolitionist but also a feminist because she challenged the church that touted their inclusiveness then denied her. It was through her abolitionist pursuits that she became more sensitive to the rights that women were denied. She opposed being subject to men so much to the point that she refused to marry. Both Sarah and Angelina both became very involved in the anti-slavery movement, they both published volumes of literature and letters on the topic. When they became well known, they began lecturing around the country on the issue. At the time women did not speak in public, this was another way that Sarah was viewed as a feminist ground breaker. Sarah openly challenged women’s domestic roles, and she believed that in order for women to be able to challenge slavery they also needed to be equal.[citation needed]

See also

Books

- Claus Bernet (2010). Bautz, Traugott. ed (in German). Sarah Grimké. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). 31. Nordhausen. cols. 559–564. ISBN 3-88309-544-8. http://www.bautz.de/bbkl/g/grimke_s_m.shtml.

- Downing, David C. A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy. Nashville: Cumberland House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9

- Harrold, Stanley. (1996). The Abolitionists and the South, 1831-1861. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

- Lerner, Gerda, The Grimke Sisters From South Carolina: Pioneers for Women's Rights and Abolition. New York, Schocken Books, 1971 and The University of North Carolina Press, Cary, North Carolina, 1998. ISBN 0195106032.

- Perry, Mark E. Lift Up Thy Voice: The Grimke Family's Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders. New York: Viking Penguin, 2002 ISBN 0142001031

References

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Taylor, Marion A., & Weir, Heather E. (2006). Let her speak for herself: nineteenth century women writing on women of genesis.p.42

- ^ Durso, Pamela R. (2003). The Power of Woman: The life and writings of Sarah Moore Grimke. Mercer University Press

- ^ Durso, 2003

- ^ Lerner, p. 25.

- ^ Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, addressed to Mary S. Parker, President of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

- ^ Ceplair, Larry. (1989). The Public Years of Sarah and Angelina Grimke: Selected Writings. New York: Columbia University Press.(p.xv)

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Lerner, Gerda. (1998). The Feminist Thought of Sarah Grimké, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Ritchie, Joy (2001). Available Means. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- ^ Ceplair, 1989

- ^ Lerner, 1998

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Lumpkin, Shirley American Women Prose Writers: 1820-1870. Ed. Amy E. Hudock and Katharine Rodier. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 239. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. From Literature Resource Center.

External links

- Picture and biographic information

- [1]

- Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, addressed to Mary S. Parker, President of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

"Grimké, John Faucheraud". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Grimké, John Faucheraud". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

Categories:- American abolitionists

- 1792 births

- 1873 deaths

- Grimké family

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- Women in the American Civil War

- American Quakers

- Feminism and history

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.