- Proximate and ultimate causation

-

For the notion of proximate cause in law, see proximate cause.

In philosophy a proximate cause is an event which is closest to, or immediately responsible for causing, some observed result. This exists in contrast to a higher-level ultimate cause (or distal cause) which is usually thought of as the "real" reason something occurred.

- Example: Why did the ship sink?

- Proximate cause: Because it was holed beneath the waterline, water entered the hull and the ship became denser than the water which supported it, so it couldn't stay afloat.

- Ultimate cause: Because the ship hit a rock which tore open the hole in the ship's hull.

In most situations, an ultimate cause may itself be a proximate cause for a further ultimate cause. Hence we can continue the above example as follows:

- Example: Why did the ship hit the rock?

- Proximate cause: Because the ship failed to change course to avoid it.

- Ultimate cause: Because the ship was under autopilot and the autopilot's data was inaccurate.

Separating proximate from ultimate causation frequently leads to better understandings of the events and systems concerned.

Contents

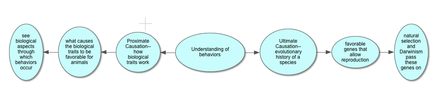

In Biology

- Ultimate causation answers questions of why an animal behaves the way it does. Ultimate causes take into account environmental factors that contribute to why an animal is able to survive and reproduce. They tie directly into the concepts of Darwinism and natural selection. Ultimate causation has an end goal in forwarding genes and ensuring survival.

- Example: A female songbird is attracted to male songbirds' songs. These songs also warn other males to stay away from the singer’s territory. Male songbirds that sang in the spring were naturally selected for; they attracted more mates, reproduced more, and passed their genes on.

- Proximate causation answers questions of how biological traits operate in an animal. Whereas ultimate causation has long-term implications, proximate causes have more immediate effects. These causes explain why certain animals have certain appendages, for example, but are independent of the evolutionary discussion.

- Example: Increased light during springtime triggered the male songbirds brain to produce a sex hormone. These hormones drove the birds to sing.

According to E. Mayr, “There is always a proximate set of causes and an ultimate set of causes; both have to be explained and interpreted for a complete understanding of the given phenomenon.” To understand both the biological and evolutionary importance of behaviors, it’s essential to determine both the proximate and ultimate causes of behaviors. Greenberg states that: "Ultimate and proximate causes are not incompatible explanations; they are simply on different scales.” In the songbird example, we can see the survival aspect of the behavior (ultimate) and the biological aspect through which the behavior occurs (proximate).

Ultimate and proximate causation tie into functionalism, which is “an attempt to explain behavior in terms of what it accomplishes for the behaving individuals.” The psychological perspective of functionalism looks at the traits of mammalian ancestors and attempts to explain how those traits helped each member to pass their genes on.

Criticisms of the terms proximate and ultimate have arisen in recent years. B. Thierry argues that the two terms are too uniformitarian, and fail to take into account genetic drift and environmental inheritance. He states that several biologists have dubbed the terms obsolete, because they focus too heavily on external factors. Now, rather, these terms are utilized regularly by behavioral psychologists and ecologists. He states: “Today many of us are keen on integrating mechanisms, development, adaptation and historical contingency in a unified theory of evolution. To this aim, however, trying to reconcile proximate and ultimate causation is counter-productive, for this very formulation perpetuates their separation.”[citation needed]

In Ethology

In ethology, the study of animal behavior, causation can be considered in terms of these two mechanisms.

- Proximate causation: Explanation of an animal's behavior based on trigger stimuli and internal mechanisms.

- Ultimate causation: Explanation of an animal's behavior based on the principles of evolution. The ultimate causation requires that the behavioral and physical traits are genetically heritable, and explains behavior by correlating behavioral traits to mechanisms that favor evolutionary development, such as natural selection.

These can be further divided, for example proximate causes may be given in terms of local muscle movements or in terms of developmental biology (see Tinbergen's four questions).

In Sociology

Proximal causation: explanation of human social behaviour by considering the immediate factors, such as symbolic interaction, understanding (Verstehen), and individual milieu that influence that behaviour. Most sociologists recognize that proximal causality is the first type of power humans experience; however, while factors such as family relationships may initially be meaningful, they are not as permanent, underlying, or determining as other factors such as institutions and social networks (Naiman 2008: 5).

Distal causation: explanation of human social behaviour by considering the larger context in which individuals carry out their actions. Proponents of the distal view of power argue that power operates at a more abstract level in the society as a whole (e.g., between economic classes) and that "all of us are affected by both types of power throughout our lives" (ibid). Thus, while individuals occupy roles and statuses relative to each other, it is the social structure and institutions in which these exist that are the ultimate cause of behaviour. A human biography can only be told in relation to the social structure, yet it also must be told in relation to unique individual experiences in order to reveal a complete picture (Mills 1959).

References

- Greenberg, Neil. "Proximate and Ultimate Causation." Deep Ethology. 22 Feb 2005. University of Tennessee. 19 Nov 2008 <https://notes.utk.edu/Bio/greenberg.nsf/0/540e727287c6e82a85256d28004f99d5?OpenDocument>.

- Alessi, G. (1992, November) Models of Proximate and Ultimate Causation in Psychology, American Psychologist, Vol 47(11) Special issue: Reflections on B. F. Skinner and psychology. pp. 1359-1370

- Gray, P. (2007) Psychology (5th Ed.) (pp. 64-66) New York: Worth Publishers

- Greenberg, G. (1998) Comparative Psychology: A Handbook. US: Taylor & Francis. pp. 666

- Mayr, E. (1988). Toward a new philosophy of biology: Observations of an evolutionist. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mills, C.W. ([1959] 2000). The Sociological Imagination. 40th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Naiman, J. (2008). How Societies Work: Class, Power and Change in a Canadian Context. 4th ed. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

- Thierry, B. (2004, October 10). Integrating proximate and ultimate causation: Just one more go!, Current Science, Vol. 89 (7), 73-79. Retrieved from http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/oct102005/1180.pdf

Categories:- Causality

- Evolutionary biology terminology

- Example: Why did the ship sink?

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.