- Dictabelt evidence relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy

-

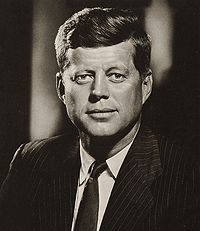

The Dictabelt evidence relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy comes from a Dictabelt recording from a microphone stuck in the open position on a motorcycle police officer's radio when John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States was assassinated in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. Many aspects of his assassination have been investigated, and the less well-known recording, made by a then-common Dictaphone dictation machine that recorded sounds in grooves pressed into a thin celluloid belt, gained prominence among Kennedy assassination conspiracy theorists starting in 1978.

The recording was made from Dallas police radio channel 1, which carried routine police radio traffic (channel 2 was reserved for special events, such as the presidential motorcade). The open-microphone portion of the recording lasts 5.5 minutes, and begins about 12:29 p.m. local time, about a minute before the assassination at 12:30 p.m.[1][2][3][4][5] Verbal time stamps were made periodically by the police radio dispatcher and can be heard on the recording.[6]

Contents

House Select Committee on Assassinations

In December 1978, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) had prepared a draft of its final report, concluding that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone as the assassin. However, after evidence from the Dictabelt recording was made available, the HSCA quickly reversed its conclusion and declared that a second gunman had fired the third of fourth shots heard. G. Robert Blakey, chief counsel of the HSCA, later said, "If the acoustics come out that we made a mistake somewhere, I think that would end it." Despite serious criticism of the scientific evidence and the HSCA's conclusions, speculation regarding the Dictabelt and the possibility of a second gunman persisted.

Investigators compared "impulse patterns" (suspected gunshots and associated echos) on the Dictabelt to 1978 test recordings of Carcano rifles fired in Dealey Plaza from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository and from a stockade fence on the grassy knoll forward and to the right of the location of the presidential limousine. On this basis, the acoustics firm of Bolt, Beranek and Newman concluded that impulse patterns 1, 2, and 4 were shots fired from the Depository, and that there was a 50% chance that impulse pattern 3 was a shot from the grassy knoll. Acoustics analysts Mark Weiss and Ernest Aschkenasy, of Queens College, reviewed the BBN data and concluded that "with the probability of 95% or better, there was indeed a shot fired from the grassy knoll."[7]

Dr. James E. Barger, of Bolt, Beranek and Newman, testified to the HSCA that his statistical analysis of the impulse patterns captured on the Dallas police recordings showed that the motorcycle with the open microphone was approximately "120 to 138 feet" behind the presidential limousine at the time of the first shot.[8] When the HSCA asked Weiss about the location of the motorcycle with the open microphone—"Would you consider that to be an essential ingredient in the ultimate conclusion of your analysis?"—Weiss answered, "It is an essential component of it, because, if you do not put the motorcycle in the place that it is [at]—the initial point of where it was receiving the [sound of the gunfire]—, and if you do not move it at the velocity at which it is being moved on paper in this re-creation, you do not get a good, tight pattern that compares very well with the observed impulses on the police tape recording."[9]

The HSCA, using an amateur film shot of the motorcade,[10] concluded that the recording originated from the motorcycle of police officer H. B. McLain, who later testified before the committee that his microphone was often stuck in the open position. However, McLain did not hear the actual recording until after his testimony, and upon hearing it he adamantly denied that the recording originated from his motorcycle. He said that the other sounds on the tape did not match his movements. Sirens are not heard on the tape until more than two minutes after what is supposed to be the sound of the shooting; however, McLain accompanied the motorcade to Parkland Hospital immediately after the shooting, with sirens blaring the entire time. When the sirens are heard on the Dictabelt recording, they rise and recede in pitch (the Doppler effect) and volume, as if passing by. McLain also said that the engine sound was clearly from a three-wheeled motorcycle, not the two-wheeler that he drove: "There's no comparison to the two sounds."[11]

Other audio discrepancies also exist. Crowd noise is not heard on the Dictabelt recording, despite the sounds generated from the many onlookers along Dallas's Main Street and in Dealey Plaza (crowd noises can be heard on at least ten channel-2 transmissions from the motorcade). Someone is heard whistling a tune about a minute after the assassination.[12]

Four of the twelve HSCA members dissented to the HSCA's conclusion of conspiracy based on the acoustic findings, and a fifth thought a further study of the acoustic evidence was "necessary".[13]

Criticism

Richard E. Sprague, an expert on photographic evidence of the assassination and a consultant to the HSCA, noted that the amateur film the HSCA relied on showed that there were no motorcycles between those riding alongside the rear of the presidential limousine and H.B. McLain's motorcycle, and that other films[14] showed McLain's motorcycle was actually 250 feet behind the presidential limousine when the first shot was fired, not 120 to 138 feet. No motorcycle was anywhere near the target area.[15]

The adult magazine Gallery published a flexi disc of the Dictabelt recording in its July 1979 issue[citation needed]. Ohio rock drummer Steve Barber listened to that recording repeatedly and heard the words "Hold everything secure" at the point where the HSCA had concluded the assassination shots were recorded. However, those words were spoken by Sheriff Bill Decker about a minute after the assassination, so the shots could not be when the HSCA claimed.[16]

After the FBI disputed the validity of the acoustic evidence, the Justice Department paid for the National Academy of Sciences to review it. The National Academy of Sciences is a U.S. corporation operating with a Title 36 congressional charter.[17]

A panel of scientists headed by Dr. Norman Ramsey issued a report in 1982 which agreed with Barber and determined that there was no compelling evidence for gunshots on the recording and that the HSCA's suspect impulses were recorded about a minute after the shooting happened.

Dr. Barger, the HSCA's acoustics expert, when asked about this discovery and the NAS analysis, replied,

Barber discovered a very weak spoken phrase on the DPD Dictabelt recording that is heard at about the time of the sound impulses we concluded were probably caused by the fourth shot. The NAS Committee has shown to our satisfaction that this phrase has the same origin as the same phrase heard also on the Audograph recording.[18] The Audograph recording was originally made from the channel 2 radio. The common phrase is heard on channel 2 about a minute after the assassination would appear, from the context, to have taken place. Therefore, it would seem . . . that the sounds that we connected with gunfire were made about a minute after the assassination shots were fired. Upon reading the NAS report, we did a brief analysis of the Audograph dub that was made by the NAS Committee and loaned to us by them. We found some enigmatic features of this recording that occur at about the time that individuals react to the assassination. Therefore, we have doubt about the time synchronization of events on that recording, and so we doubt that the Barber hypothesis is proven. The NAS Committee did not examine the several items of evidence that corroborated our original findings, so that we still agree with the House Select Committee on Assassinations conclusion that our findings were corroborated[19]

Donald Thomas rebuttal

An analysis published in the March 2001 issue of Science & Justice by Dr. Donald B. Thomas used a different radio transmission synchronization to put forth the claim that the National Academy of Sciences panel was in error. Thomas' conclusion, very similar to the HSCA conclusion, was that the gunshot impulses were real to a 96.3% certainty. Thomas presented additional details and support in the November 2001 and September and November 2002 issues.[20][21][22][23]

Further analysis

In 2003, an independent researcher named Michael O'Dell reported that both the National Academy and Dr. Thomas had used incorrect timelines because they assumed the Dictabelt ran continuously. When corrected, these showed the impulses happened too late to be the real shots even with Thomas's alternative synchronization. In addition, he showed that, due to a mathematical misunderstanding and the presence of a known impulse pattern in the background noise, there never was a 95% or higher probability of a shot from the grassy knoll.[24]

A November 2003 analysis paid for by the cable television channel Court TV concluded that the gunshot sounds did not match test gunshot recordings fired in Dealey Plaza any better than random noise.[25] In December 2003, Thomas responded by pointing out what he claimed were errors in the November 2003 Court TV analysis.[26]

Digital restoration

In 2003, ABC News aired the results of its investigation on a program called Peter Jennings Reporting: The Kennedy Assassination: Beyond Conspiracy. Based on computer diagrams and recreations done by Dale K. Myers, it concluded that the sound recordings on the Dictabelt could not have come from Dealey Plaza, and that Dallas Police Officer H.B. McLain was correct in his assertions that he had not yet entered Dealey Plaza at the time of the assassination.

In the March, 2005 issue of Reader's Digest, it was reported that Carl Haber and Vitaliy Fadeyev were assigned with the task of digitally restoring Dictabelt 10 by Leslie Waffen from the National Archives. Their method consisted of using sensors to map the microscopic contours of the tracks of old sound recordings without having to play them using a stylus, which would further degrade the sound. Dictabelt 10 was worn from countless playings and cracked due to improper storage.[27] By 2010 digital restoration of the Dictabelt seemed a more distant prospect, with both funding and final approval for the project unlikely to be secured in the near future.[28]

Possible origins

Left unanswered by the professional analyses was the question of whose open microphone captured the sounds recorded on the Dictabelt, if not Officer H.B. McLain. Jim Bowles, a Dallas police dispatcher supervisor in November 1963, and later Dallas County Sheriff, believes it originated from a particular officer on a three-wheeled motorcycle stationed at the Dallas Trade Mart, the original destination of President Kennedy's motorcade, along the same freeway to Parkland Hospital, which would account for the sound of sirens rushing by. McLain himself believes that it was from a different officer on a three-wheeler near the Trade Mart, who was known for his whistling. When interviewed by author Vincent Bugliosi, the officer acknowledged that his microphone could have been stuck in the open position (he did not recall hearing any transmissions for several minutes), and could later have become unstuck after he followed the motorcade to Parkland Hospital.[29]

Further reading

- Stokes, Louis (Chairman, House Select Committee on Assassinations). (29 March 1979). Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives.

- Ramsey, Norman F. (Chairman, Committee on Ballistic Acoustics, National Academy of Sciences). (1982). Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics.

- Posner, Gerald (1993), Case Closed, Random House, ISBN 0-679-41825-3, OCLC 185413533 (pp. 238–242, unraveling of acoustic evidence in JFK conspiracy finding)

- Thomas, Donald B. (14 June 2000). Echo correlation analysis and the acoustic evidence in the Kennedy assassination revisited. Science & Justice 2001 41, 21-32.

- Thomas, Donald B. (17 November 2001). The acoustical evidence in the Kennedy assassination.

- Thomas, Donald B. (September 2002). Emendations.

- Thomas, Donald B. (23 November 2002). Crosstalk: Synchronization of Putative Gunshots with Events in Dealey Plaza.

- O'Dell, Michael. (2003). The acoustic evidence in the Kennedy assassination.

- Berkovitz, Robert. (19 November 2003). Searching For Historic Noise: A Study of a Sound Recording Made on the Day of the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

- Thomas, Donald B. (December 2003). Impulsive Behavior: The CourtTV - Sensimetrics Acoustical Evidence Study.

- National Research Council, Washington, DC 1982 Report of the Committee on Ballistic Acoustics

- March 2005 Reader's Digest article Can technology settle the Lone Gunman controversy in the JFK assassination?

References

- ^ In addition, there are two earlier open-mic portions of the recording, at 12:24 p.m. (4.5 seconds) and 12:28 p.m. (17 seconds). J. C. Bowles, The Kennedy Assassination Tapes: A Rebuttal to the Acoustical Evidence Theory, 1979.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, Commission Exhibit 705, Radio log of channel 1 of the Dallas Police Department for November 22, 1963, vol. 17, p. 395.

- ^ Steve Barber, "The Acoustic Evidence: A Personal Memoir", [1]

- ^ "Reexamination of Acoustic Evidence in the Kennedy Assassination," Committee on Ballistic Acoustics, National Research Council, SCIENCE, 8 October 1982, [2]

- ^ "Signal Processing Analysis of the Kennedy Assassination Tapes," R.C. Agarwal, R. L. Garwin, and B. L. Lewis, IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, [3]

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. XVII, pp. 390-455, CE 705, Transcription of all radio transmissions from Dallas police channel 1 and channel 2 from 12:20 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., Nov. 22, 1963.

- ^ Scientists Work to Preserve 'JFK' Recording [4]

- ^ Testimony of Dr. James Barger, 5 HSCA 650.

- ^ HSCA Record 180-10120-10025, HSCA Committee Briefing, Dec. 18, 1978, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Taken by Robert Hughes.

- ^ H.B. McLain interviewed by Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, endnotes p. 177.

- ^ James C. Bowles, The Kennedy Assassination Tapes: A Rebuttal to the Acoustical Evidence Theory, Transcripts of Dallas Police Department Radio Communications, November 22, 1963, Annotated.

- ^ HSCA Report pp. 483–499, 503–509.

- ^ Taken by Elsie Dorman, Mal Couch, and Dave Wiegman.

- ^ Letter, Richard E. Sprague to Harold S. Sawyer, March 3, 1979, pp. 1–2, Sprague Collection, National Archives.

- ^ Sheriff Decker's words were broadcast on channel 2, but were apparently picked up by the microphone stuck open on channel 1 from the loudspeaker of a nearby police vehicle.

- ^ Though the granting of a charter does not mandate congressional oversight, there have nevertheless been questions about the federal government’s power to manage corporations who have received a charter.[5] Because of questions on who is responsible for the activities of these entities, the issuance of charters was officially stopped in 1992, though some exceptions have been made.

- ^ While channel 1 transmissions (routine police radio traffic) were recorded on a Dictaphone machine, channel 2 transmissions (reserved for special events such as the presidential motorcade) were recorded on a Gray Audograph machine. Both machines were located at Dallas Police headquarters.

- ^ FBI Record 124-10006-10153, Letter from James E. Barger to G. Robert Blakey, February 18, 1983, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Thomas, Donald B. (2001), "Echo correlation analysis and the acoustic evidence in the Kennedy assassination revisited" (PDF), Science & Justice (The Forensic Science Society) 41: 21–32, doi:10.1016/S1355-0306(01)71845-X, http://www.forensic-science-society.org.uk/Thomas.pdf

- ^ Thomas, Donald B. (November 17, 2001), Hear No Evil: The Acoustical Evidence in the Kennedy Assassination, http://pages.prodigy.net/whiskey99/hearnoevil.htm, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ Thomas, Donald B. (November 23, 2002), Crosstalk: Synchronization of Putative Gunshots with Events in Dealey Plaza, archived from the original on 2008-05-05, http://web.archive.org/web/20080505094316/http://www.geocities.com/whiskey99a/dbt2002.html, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ Thomas, Donald B. (January 2003), Emendations, http://pages.prodigy.net/whiskey99/emendations.htm, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ O'Dell, Michael, The acoustic evidence in the Kennedy assassination, http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/odell/, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ The JFK Assassination, CourtTV.com, November 2003, archived from the original on 2003-11-06, http://web.archive.org/web/20031106032415/http://www.courttv.com/onair/shows/kennedy/, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ Thomas, Donald B. (December 2003), Impulsive Behavior: The CourtTV - Sensimetrics Acoustical Evidence Study., http://pages.prodigy.net/whiskey99/courttv.htm, retrieved 2008-07-30

- ^ Can Technology Solve the JFK Murder?: Pulling Proof From Particles | Legends & Leaders | Reader's Digest

- ^ " New Acoustics Research?" Education Forum 19 March 2010 Retrieved 10 April 2010

- ^ Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, endnotes pp. 184–190.

Assassination of John F. Kennedy Assassination Aftermath Autopsy · Reaction · Johnson inauguration · Funeral (Foreign Dignitaries) · Jack Ruby · Ruby v. Texas · Warren Commission · House Select Committee on Assassinations · Dictabelt evidence · Conspiracy theories · Single bullet theory · In popular culture · The Kennedy Half-Century

Categories:- Assassination of John F. Kennedy

- Sound recording

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.