- Clarel

-

Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land is an American epic poem by Herman Melville, published in two volumes in 1876. Clarel is the longest poem in American literature, stretching to almost 18,000 lines (longer even than European classics such as the Iliad, Aeneid and Paradise Lost). As well its great length, Clarel is notable for being the major work of Melville's later years; in the three decades between The Confidence Man (1857) and Billy Budd (completed circa 1891), Melville devoted himself solely to writing poetry, with Clarel and the short American Civil War collection, Battle Pieces, being his most significant achievements.

Contents

Plot

Jerusalem

Clarel, a young theology student whose belief has begun to waver, travels to Jerusalem to renew his faith in the sites and scenes of Jesus Christ’s mortal ministry. He stays in a hostel run by Abdon, the Black Jew—a living representation of Jerusalem. Clarel is initially amazed by the religious diversity of Jerusalem; he sees Jews, Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists walking its streets and recognizes their common faith in divinity. Clarel also senses a kinship with an Italian youth and Catholic doubter named Celio, whom he sees walking in the distance, but does not take the initiative and greet him. When Celio dies shortly thereafter, Clarel feels he may have passed up an opportunity to regain his faith.

While walking through Jerusalem’s streets, Clarel meets Nehemiah, a Christian who hands out proselytizing tracts to pilgrims and tourists. Nehemiah becomes Clarel’s guide and shows him the sights of Jerusalem. At the Wailing Wall, Clarel notices an American Jew and his daughter Ruth, and Nehemiah later introduces Clarel to Ruth, with whom the divinity student falls in love. But Jewish custom and a jealous Rabbi keep Clarel and Ruth apart much of the time, so Clarel continues sightseeing with Nehemiah.

In Gethsemane, Clarel meets Vine and Rolfe, two opposites. Rolfe is a Protestant and religious skeptic who historicizes Jerusalem and calls into question Christ's claim to divinity. Vine is a quiet man whose example leads Clarel to hope for faith—at least initially. When Vine and Rolfe decide to take a tour of other important sites in the Holy Land—the wilderness where John the Baptist preached, the monastery at Mar Saba and Bethlehem—Clarel wants to accompany them, but he does not wish to leave Ruth.

At this critical juncture, Ruth's father Nathan dies, and Jewish customs prohibit Clarel’s presence, so he decides to take the journey, confident that he will see his beloved when he returns to Jerusalem. The night before his journey, a frieze depicting the death of a young bride makes him pause with foreboding, but he banishes his doubts and sets off on his pilgrimage anyways.

The Wilderness

Clarel sets off on his tour of Palestine with a wide range of fellow travelers—Nehemiah, Rolfe and Vine accompany him, but Melville also introduces new characters for this book: Djalea, son of an Emir turned tour guide; Belex, the leader of six armed guards protecting the pilgrimage; a Greek banker and his son-in-law Glaucon; a Lutheran priest named Derwent; an unnamed former elder who has lost the faith; and a Swedish Jew named Mortmain, whose black skull cap constantly forebodes ill. The tour through the desert starts with an explicit invitation to compare Clarel and his companions’ journey to “brave Chaucer’s” Canterbury pilgrims.

The banker and his son-in-law soon abandon the group for a caravan headed back to Jerusalem, unaccustomed to desert hardships. When Clarel and his companions come to the stretch of road where Christ’s good Samaritan rescued a waylaid Jew from robbers, the taciturn elder also departs, scoffing at the cautions of Djaleal and Belex, who fear robbers. Mortmain is the final deserter; he leaves before the party makes a stop at Jericho, refusing to enter a city he considers wicked. During their travels, Clarel’s company is joined by Margoth, an apostate Jew geologist who scoffs at the faith expressed by Derwent and whose presence at the atheistic extreme prompts Rolfe to move closer to Derwent’s faith than he had formerly been. The company also speaks briefly with a Dominican monk traveling through the desert.

In the absence of these travelers, Derwent and Rolfe engage in a number of heated debates as to the veracity of biblical accounts and the relationship between the various Protestant sects. Derwent staunchly maintains his faith in biblical accuracy, while Rolfe questions the Holy Book’s factuality even as he acknowledges his desire to believe. Clarel eagerly listens to these conversations but rarely participates, unsure of whether his faith is being shored up or torn down by the debates. He frequently looks to Vine for companionship and reassurance, but Vine’s stoic silence resists interpretation, and Vine denies Clarel’s request that he speak more freely and intimately.

When the party arrives at the Dead Sea, they make camp, and Mortmain rejoins them. The Jew seems crazed and drinks the bitter Dead Sea water despite warnings that it is poisonous. Mortmain survives his draught, but when the pilgrims wake in the morning, they discover that Nehemiah has died in the night, after seeing a vision of John’s heavenly city in the air, above the ruins of Sodom and Gomorrah. While the company buries the saint by the Dead Sea, Clarel looks out over the water and sees a faint rainbow which seems to offer hope, as it did for Noah, but the bow “showed half spent— / Hovered and trembled, paled away, and—went.”

Mar Saba

From the shores of the Dead Sea, Clarel and the other pilgrims travel to the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Saba, where one St. Saba discovered a fountain in the desert and planted a palm tree now more than one thousand years old. On their way to the monastery they meet a young man from Cyprus who has just left Mar Saba and is traveling to the Dead Sea, making a journey the reverse of Clarel’s. The Cypriot's faith is unshaken, and all who hear his singing envy his faith. On their way to Mar Saba, the travelers also pass through the “tents of Kedar” where a band of robbers camp and exact a toll of travelers to the monastery. These robbers recognize royalty in Djalea, however, and let the pilgrims pass without molesting them.

At Mar Saba, Clarel and his friends are fed by the monks and entertained with a masque telling the story of Cataphilus, a wandering Jew who bears an uncanny resemblance to Clarel, who has lost his faith “and meriteth no ruth.” The monks then leave the group with a Muslim merchant visiting the monastery named Lesbos. Lesbos leads the group in a drunken revel, inducing even the staid Derwent to participate. He also introduces the group to Agath, another visitor at Mar Saba and a Greek sailor who was sent to Mar Saba to recover after being waylaid and beaten in the Judean desert a la the wounded Jew in Christ’s parable of the Good Samaritan. Agath and Lesbos tell several sea stories to Clarel, who listens attentively to tales reminiscent of Melville’s White-Jacket and Captain Ahab.

In conversations between various combinations of the various pilgrims and monastery inhabitants, Clarel learns that no one has faith—not Vine, Rolfe, Belex, Lesbos—not even Derwent, whose professions to this point had been staunch. After confessing his lack of faith to Clarel, Derwent takes a tour of the monastery but cannot appreciate the monks’ faith; he scoffs at the holy relics showed him by the abbot, considers several of the monks to be insane, and cannot believe that the holy palm tree is either holy or a thousand years old. When he takes his eyes from the palm, Derwent sees Mortmain’s skull cap flutter down from an outcropping where the Jew is laying and observing the palm.

All of the pilgrims fall asleep looking at the palm tree, and in the morning, when the caravan is about to leave, Mortmain is missing. His glassy, dead eyes are fixed on the tree, and the monks bury the Jew outside the monastery, in an unconsecrated grave, “Where vulture unto vulture calls, / And only ill things find a friend.”

Bethlehem

When the pilgrims leave Mar Saba, they take Lesbos and Agath with them—but Lesbos turns back after a short distance and rides back to the monastery with a military salute. Ungar, a new traveling companion, also joins the company. He is a veteran of the American Civil War, the descendant of Catholic colonists and American Indians and the only pilgrim with faith. This new group travels to Bethlehem together. Once in Bethlehem, Agath leaves to join a new caravan, and the remaining pilgrims pay Djaleal and Belex for their services in guiding them through the dangerous wilderness.

Ungar’s faith attracts Clarel but antagonizes Derwent, who resents Ungar’s insistence that man is fallen and cannot reclaim his lost glory without divine aid. Their debates over human nature and religion also address the morality of democracy and capitalism. Vine, Rolfe and Clarel, all Americans, take Ungar’s part, leaving the Englishman to believe that they argue with him over prejudice against the Old World.

In Bethlehem, the group is shown the cave where Christ was born by a young Franciscan monk named Salvaterra—whose name means save the earth and who seems almost divine, a reincarnation of the original St. Francis. The monk further inspires Clarel’s faith, and though the party traveled to Bethlehem without that star to guide them that led the wise men to Christ’s birth, Clarel’s faith is strengthened after his time with Ungar and Salvaterra, and he views the setting sun as an inspiring beacon.

But Ungar leaves the group and Salvaterra remains in the monastery, leaving Clarel to grapple with his fledgling faith by himself. He returns to Jerusalem hopeful, eager to rescue Ruth and Agar from their exile in Palestine and return them both to the United States. But when Clarel approaches Jerusalem during the night before Ash Wednesday, he meets a Jewish burial party. In his absence, Ruth and Agar have died, and Clarel’s new-found faith is rocked to its depths. All through the celebration of Christ’s last week on earth Clarel waits for a miracle—for Ruth to return from the dead as Christ did. But Easter passes without Ruth’s resurrection, and Clarel is left a lone man in Jerusalem, wondering why though “They wire the world—far under sea / They talk; but never comes to me / A message from beneath the stone.”

Epilogue

The last canto of Clarel offers Melville’s commentary on the existential crisis of faith which Clarel faces in the wake of Ruth’s death. Though Clarel remains beset by troubles and doubts, Melville clearly offers the poem as an exordium to faith:

"Then keep thy heart, though yet but ill-resigned—

Clarel, thy heart, the issues there but mind;

That like the crocus budding through the snow—

That like a swimmer rising from the deep—

That like a burning secret which doth go

Even from the bosom that would hoard and keep;

Emerge thou mayst from the last whelming sea,

And prove that death but routs life into victory."

Origins

Melville had visited the Holy Land himself in the winter of 1856, when he had travelled by the same route that he describes in Clarel. The visit followed a trip to England on October of the same year, in which he met Nathaniel Hawthorne, and gave him the manuscript for what amounted to his 'farewell to prose,' The Confidence Man. Hawthorne later recorded his troubled impression of Melville on this occasion, noting how they

"took a pretty long walk together, and sat down in the hollow among the sand hills (sheltering ourselves from the high, cool wind) and smoked a cigar. Melville, as he always does, began to reason of Providence and futurity, and of everything that lies beyond human ken, and informed me that he had pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated; but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation; and, I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. It is strange how he persists -- and has persisted ever since I knew him, and probably long before -- in wandering to and fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sand hills amid which we were sitting. He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other."[1]

In consulting the Journal of a Visit to Europe and the Levant, Melville's record of the winter voyage of 1856 (which took him five months and 15,000 miles), it is clear that he was not relieved of either his doubts or his melancholy. Sailing through the Greek Islands, he became disillusioned by classical mythology, and this response was extended to his encounter with Jerusalem itself. Passing Cyprus, on the way home, he wrote: "From these waters rose Venus from the foam. Found it as hard to realize such a thing as to realize on Mt Olivet that from there Christ rose." (p. 164)

The poem thus shows Melville revisiting and exploring his realization that the Old World sites of religious pilgrimage are barren and meaningless objects in themselves. As he writes in the opening Canto:

Like the ice-bastions round the Pole,

Thy blank, blank towers, Jerusalem!The modernist implication of these lines is striking, anticipating the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure (who graduated from university the year the poem was published); the "Signifier" of Jerusalem is revealed as a "blank", with the "Signified" of the physical "towers" failing to contain any sacred meaning.

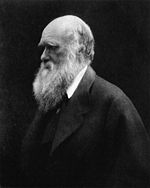

As well as this focus on the divide between the preternatural, the religious, and historical reality, Melville's poem is concerned with the crisis faced by mid-19th century Christianity in the wake of the discoveries of Charles Darwin. Melville saw these scientific developments as simultaneously fascinating (cf. the focus on natural history in Moby-Dick) and terrifying, representing a challenge to traditional Christianity that was almost apocalyptic in its significance, especially when combined with the more theological attacks of Protestantism. As he writes in the famously troubled, and inconclusive, Epilogue to the work:

If Luther's day expand to Darwin's year,

Should that exclude the hope -- foreclose the fear?Form

The poem is composed in irregularly rhymed iambic tetrameter (except for the Epilogue), and contains 150 Cantos divided into four books: Jerusalem, The Wilderness, Mar Saba, and Bethlehem.

Trying to determine the strange appeal of the work's "detuned poetic style", William C. Spengeman has suggested that the "impacted tetrameters of Clarel" reveal the origin of the "modernist note", and that they thus anticipate the "prosody of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot and William Carlos Williams".[2]

Similarly, Walter E. Bezanson notes the "curious mixture of the archaic and the contemporary both in language and materials", leading to the inclusion of antique words such as "kern, scrip, carl, tilth and caitiff", alongside modern technical terms taken "from ship and factory, from the laboratory, from trading, seafaring, and war." Commenting on the rhyme-scheme and the restricted meter, Bezanson responded to the common objection that Melville ought to have composed the work in prose, or at least in blank verse, arguing:

To wish that Clarel had been written in blank verse, for example, is simply to wish for a completely different poem. In earlier years Melville had often set Shakespearean rhythms echoing through his high-keyed prose with extraordinary effect. But now the bravura mood was gone. Melville did not propose a broad heroic drama in the Elizabethan manner. Pentameter -- especially blank verse -- was too ample and overflowing for his present mood and theme. The tragedy of modern man, as Melville now viewed it, was one of constriction... Variations from the basic prosodic pattern are so infrequent as to keep the movement along an insistently narrow corridor.[3]

Reception

Contemporary

The poem was barely noticed on its original publication, and the few reviews that did appear showed that mainstream critical taste in the States leant towards the polished, genteel lines of poets such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell. The New York Times was the first to insist that "it should have been written in prose," while the reviewer for the World complained that he had got "lost in the overwhelming tide of mediocrity." The Independent called it a "vast work... destitute of interest or metrical skill," and Lippincott's Magazine claimed that there were "not six lines of genuine poetry in it." In his collection of these quotes, Walter E. Bezanson suggests that the overwhelmingly negative response was partly due to the fact that none of the critics had "actually read it," noting in particular the Lippincott critic's baffling comment that the poet was evidently a "bright and genial" individual,[4] an observation entirely out of keeping with the tone of the vast majority of the work.

Early 20th century

Subsequent criticism, especially since the so-called "Melville Revival" of the early-20s, has been kinder to the poem. Frank Jewett Mather called it the "America's best example of Victorian faith-doubt literature", and Raymond Weaver declared that it contained "more irony, vividness and intellect than almost all the contemporary poets put together." In 1924, amid the rising tide of literary modernism John Middleton Murry approvingly noted the "compressed and craggy" quality of Melville's poetic line, and the French critic Jean Simon called the work "an extraordinary revelation of a tormented soul."

Post World War II

Seeing the whole work as an obscure elder sibling to T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, Richard Chase has argued that the "sterility of modern life is the central symbolic idea of the poem," and that after the "extremities of titanism in Pierre", Melville now reached the culmination of his later thought: "the core of the high Promethean hero." These remarks paved the way for a generation of critics who saw the poem as the crucial document of Melville's later years, such as Ronald Mason, who reads the poem as "a contemplative recapitulation of all Melville's imaginative life," and Newton Arvin, who calls it "Melville's great novel of ideas in verse."[5]

In 1994, Harold Bloom chose Clarel as one of four Melville works to be included in his Western Canon.[6]

References

- ^ Nathaniel Hawthorne's Journal (1973), ed. C. E. Frazer Clarke

- ^ William C. Spengeman, Introduction to Pierre, or The Ambiguities (1996), p. xviii

- ^ Walter E. Bezanson, Introduction to Clarel (1960), pp. lxvi-lxvii

- ^ Bezanson (1960), pp. xl-xli

- ^ Bezanson (1960), pp. xlvii-xlviii

- ^ Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages (1994). The other Melville works Bloom included were Moby-Dick, The Piazza Tales and Billy Budd.

Works by Herman Melville Novels Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846) · Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847) · Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849) · Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) · White-Jacket, or The World in a Man-of-War (1850) · Moby-Dick, or The Whale (1851) · Pierre: or, The Ambiguities (1852) · Isle of the Cross (ca 1853, lost) · Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1856) · The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857) · Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative) (1924)Short story

collectionsThe Piazza Tales (1856)Short stories "The Piazza" · "Bartleby, the Scrivener" · "Benito Cereno" · "The Lightning-Rod Man" · "The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles" · "The Bell-Tower" (all 1856) Uncollected : "Cock-A-Doodle-Doo!" (1853) · "Poor Man's Pudding and Rich Man's Crumbs" (1854) · "The Happy Failure" (1854) · "The Fiddler" (1854) · "Paradise of Bachelors and Tartarus of Maids" (1855) · "Jimmy Rose" (1855) · "The 'Gees" (1856) · "I and My Chimney" (1856) · "The Apple-Tree Table" (1856)

Unpublished in Melville's lifetime : "The Two Temples" · "Daniel Orme"Poetry Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) · Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876) · John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) · Timoleon (1891) · Weeds and Wildings, and a Rose or Two (1924)

Uncollected/unpublished poems: "Epistle to Daniel Shepherd" · "Inscription for the Slain at Fredericksburgh" · "The Admiral of the White" · "To Tom" · "Suggested by the Ruins of a Mountain-temple in Arcadia" · "Puzzlement" · "The Continents" · "The Dust-Layers" · "A Rail Road Cutting near Alexandria in 1855" · "A Reasonable Constitution" · "Rammon" · "A Ditty of Aristippus" · "In a Nutshell" · "Adieu"Essays Hawthorne and His Mosses (1850)Categories:- 1876 poems

- American poems

- Epic poems in English

- Poetry by Herman Melville

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.