- Rado graph

-

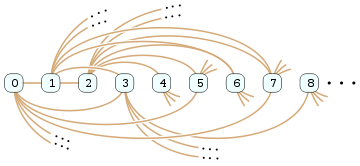

The Rado graph, as numbered by Rado (1964).

The Rado graph, as numbered by Rado (1964).

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the Rado graph, also known as the random graph or the Erdős–Renyi graph, is the unique (up to isomorphism) countable graph R such that for any finite graph G and any vertex v of G, any embedding of G − v as an induced subgraph of R can be extended to an embedding of G into R. As a result, the Rado graph contains all finite and countably infinite graphs as induced subgraphs.

Contents

History

The Rado graph was introduced by Richard Rado (1964), although the symmetry properties of the same graph, constructed in a different way, had already been studied by Erdős & Rényi (1963).

Construction via binary numbers

Rado (1964) constructs the Rado graph as follows. He identifies the vertices of the graph with the natural numbers 0, 1, 2, ... An edge xy exists in the graph whenever either the xth bit of the binary representation of y is nonzero (in this case x < y), or, symmetrically, if the yth bit of the binary representation of x is nonzero (in this case x > y). Thus, for instance, the neighbors of vertex 0 consist of all odd-numbered vertices, while the neighbors of vertex 1 consist of vertex 0 (the only vertex whose bit in the binary representation of 1 is nonzero) and all vertices with numbers congruent to 2 or 3 modulo 4.

Finding isomorphic subgraphs

The Rado graph satisfies the following extension property: for any finite disjoint sets of vertices U and V, there exists a vertex x connected to everything in U, and to nothing in V. For instance, let

Then the nonzero bits in the binary representation of x cause it to be adjacent to everything in U. However, x has no nonzero bits in its binary representation corresponding to vertices in V, and x is so large that the xth bit of every element of V is zero. Thus, x is not adjacent to any vertex in V.

This idea of finding vertices adjacent to everything in one subset and nonadjacent to everything in a second subset can be used to build up isomorphic copies of any finite or countably infinite graph G, one vertex at a time. For, let Gi denote the subgraph of G induced by its first i vertices, and suppose that Gi has already been identified as an induced subgraph of a subset S of the vertices of the Rado graph. Let v be the next vertex of G, let U be the neighbors of v in Gi, and let V be the non-neighbors of v in Gi. If x is a vertex of the Rado graph that is adjacent to every vertex in U and nonadjacent to every vertex in V, then S ∪ {x} induces a subgraph isomorphic to Gi + 1.

By induction, starting from the 0-vertex subgraph, every finite or countably infinite graph is an induced subgraph of the Rado graph.

Uniqueness

The Rado graph is, up to graph isomorphism, the only countable graph with the extension property. For, let G and H be two graphs with the extension property, let Gi and Hi be isomorphic induced subgraphs of G and H respectively, and let gi and hi be the first vertices in an enumeration of the vertices of G and H respectively that do not belong to Gi and Hi. Then, by applying the extension property twice, one can find isomorphic induced subgraphs Gi + 1 and Hi + 1 that include gi and hi together with all the vertices of the previous subgraphs. By repeating this process, one may build up a sequence of isomorphisms between induced subgraphs that eventually includes every vertex in G and H. Thus, by the back-and-forth method, G and H must be isomorphic.[1]

By applying the same construction to two isomorphic subgraphs of the Rado graph, it can be shown that the Rado graph is ultrahomogeneous: any isomorphism between any two induced subgraphs of the Rado graph extends to an automorphism of the entire Rado graph.[1] In particular, there is an automorphism taking any ordered pair of adjacent vertices to any other such ordered pair, so the Rado graph is a symmetric graph.

Robustness against finite changes

If a graph G is formed from the Rado graph by deleting any finite number of edges or vertices, or adding a finite number of edges, the change does not affect the extension property of the graph: for any pair of sets U and V it is still possible to find a vertex in the modified graph that is adjacent to everything in U and nonadjacent to everything in V, by adding the modified parts of G to V and applying the extension property in the unmodified Rado graph. Therefore, any finite modification of this type results in a graph that is isomorphic to the Rado graph.

Partition property

For any partition of the vertices of the Rado graph into two sets A and B, or more generally for any partition into finitely many subsets, at least one of the subgraphs induced by one of the partition sets is isomorphic to the whole Rado graph. Cameron (2001) gives the following short proof: if none of the parts induces a subgraph isomorphic to the Rado graph, they all fail to have the extension property, and one can find pairs of sets Ui and Vi that cannot be extended within each subgraph. But then, the union of the sets Ui and the union of the sets Vi would form a set that could not be extended in the whole graph, contradicting the Rado graph's extension property. This property of being isomorphic to one of the induced subgraphs of any partition is held by only three countably infinite undirected graphs: the Rado graph, the complete graph, and the empty graph.[2] Bonato, Cameron & Delić (2000) and Diestel et al. (2007) investigate infinite directed graphs with the same partition property; all are formed by choosing orientations for the edges of the complete graph or the Rado graph.

A related result concerns edge partitions instead of vertex partitions: for every partition of the edges of the Rado graph into finitely many sets, there is a subgraph isomorphic to the whole Rado graph that uses at most two of the colors. However, there may not necessarily exist an isomorphic subgraph that uses only one color of edges.[3]

Alternative constructions

One may form an infinite graph in the Erdős–Rényi model by choosing, independently and with probability 1/2 for each pair of vertices, whether to connect the two vertices by an edge. With probability 1 the resulting graph has the extension property, and is therefore isomorphic to the Rado graph. This construction also works if any fixed probability p not equal to 0 or 1 is used in place of 1/2. This result, shown by Paul Erdős and Alfréd Rényi in 1963,[4] justifies the definite article in the common alternative name “the random graph” for the Rado graph: for finite graphs, repeatedly drawing a graph from the Erdős–Rényi model will often lead to different graphs, but for countably infinite graphs the model almost always produces the same graph. Since one obtains the same random process by inverting all choices, the Rado graph is self-complementary.

As Cameron (2001) describes, the Rado graph may also be formed by a construction resembling that for Paley graphs. Take as the vertices of a graph all the prime numbers that are congruent to 1 modulo 4, and connect two vertices by an edge whenever one of the two numbers is a quadratic residue modulo the other (by quadratic reciprocity and the restriction of the vertices to primes congruent to 1 mod 4, this is a symmetric relation, so it defines an undirected graph). Then, for any sets U and V, by the Chinese remainder theorem, the numbers that are quadratic resides modulo every prime in U and nonresidues modulo every prime in V form a periodic sequence, so by Dirichlet's theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions this number-theoretic graph has the extension property.

Related concepts

Although the Rado graph is universal for induced subgraphs, it is not universal for isometric embeddings of graphs: it has diameter two, and so any graph with larger diameter does not embed isometrically into it. Moss (1989, 1991) has investigated universal graphs for isometric embedding; he finds a family of universal graphs, one for each possible finite graph diameter. The graph in his family with diameter two is the Rado graph.

The universality property of the Rado graph can be extended to edge-colored graphs; that is, graphs in which the edges have been assigned to different color classes, but without the usual edge coloring requirement that each color class form a matching. For any finite or countably infinite number of colors χ, there exists a unique countably-infinite χ-edge-colored graph Gχ such that every partial isomorphism of a χ-edge-colored finite graph can be extended to a full isomorphism. With this notation, the Rado graph is just G1. Truss (1985) investigates the automorphism groups of this more general family of graphs.

From the model theoretic point of view, the Rado graph is an example of a saturated model.

Shelah (1984, 1990) investigates universal graphs for transfinite numbers of vertices.

Notes

- ^ a b Cameron (2001).

- ^ Cameron (1990); Diestel et al. (2007).

- ^ Pouzet & Sauer (1996).

- ^ Erdős & Rényi (1963). Erdős and Rényi use the extension property of graphs formed in this way to show that they have many automorphisms, but do not observe the other properties implied by the extension property. They also observe that the extension property continues to hold for certain sequences of random choices in which different edges have different probabilities of being included.

References

- Bonato, Anthony; Cameron, Peter; Delić, Dejan (2000), "Tournaments and orders with the pigeonhole property", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 43 (4): 397–405, doi:10.4153/CMB-2000-047-6, MR1793941, http://journals.cms.math.ca/cgi-bin/vault/view/bonato7404.

- Cameron, Peter J. (1990), Oligomorphic permutation groups, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 152, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. viii+160, ISBN 0-521-38836-8, MR1066691.

- Cameron, Peter J. (1997), "The random graph", The mathematics of Paul Erdős, II, Algorithms Combin., 14, Berlin: Springer, pp. 333–351, MR1425227.

- Cameron, Peter J. (2001), "The random graph revisited", European Congress of Mathematics, Vol. I (Barcelona, 2000), Progr. Math., 201, Basel: Birkhäuser, pp. 267–274, MR1905324.

- Diestel, Reinhard; Leader, Imre; Scott, Alex; Thomassé, Stéphan (2007), "Partitions and orientations of the Rado graph", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 359 (5): 2395–2405 (electronic), doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-06-04086-4, MR2276626.

- Erdős, P.; Rényi, A. (1963), "Asymmetric graphs", Acta Mathematica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 14: 295–315, doi:10.1007/BF01895716, MR0156334.

- Moss, Lawrence S. (1989), "Existence and nonexistence of universal graphs", Polska Akademia Nauk. Fundamenta Mathematicae 133 (1): 25–37, MR1059159.

- Moss, Lawrence S. (1991), "The universal graphs of fixed finite diameter", Graph theory, combinatorics, and applications. Vol. 2 (Kalamazoo, MI, 1988), Wiley-Intersci. Publ., New York: Wiley, pp. 923–937, MR1170834.

- Pouzet, Maurice; Sauer, Norbert (1996), "Edge partitions of the Rado graph", Combinatorica 16 (4): 505–520, doi:10.1007/BF01271269, MR1433638.

- Rado, Richard (1964), "Universal graphs and universal functions", Acta Arith. 9: 331–340, http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/aa/aa9/aa9133.pdf.

- Shelah, Saharon (1984), "On universal graphs without instances of CH", Annals of Pure and Applied Logic 26 (1): 75–87, doi:10.1016/0168-0072(84)90042-3, MR739914.

- Shelah, Saharon (1990), "Universal graphs without instances of CH: revisited", Israel Journal of Mathematics 70 (1): 69–81, doi:10.1007/BF02807219, MR1057268.

- Truss, J. K. (1985), "The group of the countable universal graph", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 98 (2): 213–245, doi:10.1017/S0305004100063428, MR795890.

Categories:- Individual graphs

- Random graphs

- Infinite graphs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.