- Clock face

-

A clock face is the part of an analog clock (or watch) that displays the time through the use of a fixed numbered dial or dials and moving hands. In its most basic form, recognized universally throughout the world, the dial is numbered 1–12 indicating the hours in a 12-hour cycle, and a short hour hand makes 2 revolutions in a day. A longer minute hand makes one revolution every hour. The face may also include a second hand which makes one revolution per minute, and other hands. The term is less commonly used for the time display on digital clocks and watches.

A second type of clock face is the 24 hour analog dial, widely used in military and other organizations that use 24 hour time. This is similar to the 12 hour dial above, except it has hours numbered 1–24 around the outside, and the hour hand makes only one revolution per day. Some special purpose clocks, such as timers and sporting event clocks, are designed for measuring periods less than one hour. Clocks can indicate the hour with Roman numerals or Hindu-Arabic numerals, or with non-numeric indicator marks. The two numbering systems have also been used in combination with the prior indicating the hour and the later the minute. Longcase clocks (also known as grandfather clocks) typically use Roman numerals for the hours. Clocks using only Arabic numerals first began to appear in the mid-18th century. The periphery of a clock's face, where the numbers and other graduations appear, is often called the chapter ring.

The clock face is so familiar that, particularly in the case of watches, the numbers are often omitted and replaced with undifferentiated hour marks. Occasionally markings of any sort are dispensed with, and the time is read by the angles of the hands. The face of the Movado "Museum Watch" is known for a single dot at the 12 o'clock position.

It is customary to display clocks and watches at 10:00, which is why almost all advertising shows them this way.

Contents

Reading a modern clock face

A ship's radio room wall clock during the age of wireless telegraphy showing '10:09' and 36 seconds'

A ship's radio room wall clock during the age of wireless telegraphy showing '10:09' and 36 seconds'

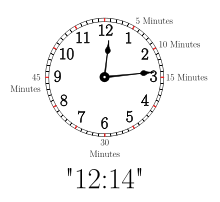

Most modern clocks have the numbers 1 through 12 printed on the face indicating the hour, and on many models, sixty dots or lines evenly spaced in a ring around the outside of the dial, indicating minutes and seconds.

The time is read by observing the placement of several "hands" which emanate from the center of the dial:

- A short thick hand (hour);

- A long, thinner hand (minute); and on some models,

- A very thin 'sweep' hand (seconds)

All the hands continuously rotate around the dial in a 'clockwise' direction - in the direction of increasing numbers.

- The sweep hand moves relatively quickly, taking a full minute (sixty seconds) to make a complete rotation from '12 to 12.' For every single rotation of the sweep hand, the minute hand will move from one minute mark to the next.

- The minute hand rotates more slowly around the dial, it takes an hour (sixty minutes) to make a complete rotation from '12 to 12.' For every single rotation of the minute hand, the hour hand will move from one hour mark to the next.

- The hour hand moves slowest of all, taking twelve hours (half a day) to make a complete rotation. When all three hands are pointing at '12' it is either noon or midnight and the process begins again.

In the example picture, showing a two handed clock, the minute hand is on "14" minutes and the hour hand is moving from '12' to '1' - this indicates a time of 12:14.

Historical development

Clocks existed before clock faces. The first mechanical clocks, built in 13th century Europe, were striking clocks: their purpose was to ring bells upon the canonical hours, to call the public to prayer. These were erected as tower clocks in public places, to ensure that the bells were audible. It was not until these mechanical clocks were in place that their creators realized that their wheels could be used to drive an indicator on a dial on the outside of the tower, where it could be widely seen.

Before the late 14th century, a fixed hand (often a carving shaped like a hand) indicated the hour by pointing to numbers on a rotating dial; after this time the current convention of a rotating hand on a fixed dial was adopted. Minute hands (so named because they indicated the small or minute divisions of the hour) only came into regular use around 1690, after the invention of the pendulum and anchor escapement increased the precision of time-telling enough to justify it.[1] St John the Evangelist, Groombridge, Kent, has a fine example of a clock with only an hour hand. In some precision clocks a third hand, which rotated once a minute, was added in a separate subdial. This was called the 'second-minute' hand (because it measured the secondary minute divisions of the hour), which was shortened to 'second' hand.[1] The convention of the hands moving clockwise evolved in imitation of the sundial. In the Northern hemisphere, where the clock face originated, the shadow of the gnomon on a sundial moves clockwise during the day.[2] This was also why noon or 12 o'clock was conventionally located at the top of the dial.

French Decimal Time

Main article: Decimal timeDuring the French Revolution in 1793, in connection with its Republican calendar, France attempted to introduce a decimal time system.[3] This had 10 decimal hours in the day, 100 decimal minutes per hour, and 100 decimal seconds per minute. Therefore the decimal hour was more than twice as long as the present hour, the decimal minute was slightly longer than the present minute and the decimal second was slightly shorter than the present second. Clocks were manufactured with this alternate face, usually combined with traditional hour markings. However, it didn't catch on, and France discontinued the mandatory use of decimal time on 7 April 1795, although some French cities used decimal time until 1801.

Stylistic development

Until the last quarter of the 17th century hour markings were etched into metal faces and the recesses filled with black wax. Subsequently, higher contrast and improved readability was achieved with white enamel plaques painted with black numbers. Initially, the numbers were printed on small, individual plaques mounted on a brass substructure. This was not a stylistic decision, rather enamel production technology had not yet achieved the ability to create large pieces of enamel. The "13 piece face" was an early attempt to create an entirely white enamel face. As the name suggests, it was composed of 13 enamel plaques: 12 numbered wedges fitted around a circle. The first single piece enamel faces, not unlike those in production today, began to appear c. 1735.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. pp. 195. ISBN 0780800087.

- ^ Lathrop, Don Haven (1996). "Why is clockwise Clockwise?". Workshop Hints. British Horological Institute. http://www.bhi.co.uk/aHints/clckwse.html. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ "The Republican Calendar and Decimal Time". History. The Horological Foundation, Netherlands. 2008. http://www.antique-horology.org/_Editorial/RepublicanCalendar/default.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

Categories:- Clocks

- Horology

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.